Folks in the farming business are unique storytellers. Many have the gift of gab, but often not of exaggeration.

Typically conservative by nature, farmers are loath to stretch the truth. Maybe it's because they figure there's another farmer within earshot. Maybe they have to pray so hard for rain—and then for it to stop—that even little white lies aren't worth the risk. The same straight-talk rules seem to apply to many farm-service professions, probably because everybody in agriculture collectively butters the same side of the bread.

But if you listened to these folks talk about farmland prices lately, you'd swear you were attending an executive meeting of the Liar's Club. So it is with farmland prices, where tales of recent sales don't need embellishment because the prices are already tall.

Curt Everson is the president of the South Dakota Bankers Association (SDBA). He was raised near Watertown, in the northeastern part of the state, on a farm that was "mostly grain but a little bit of cattle." Everson grew up in the 1970s, when $700 an acre "was pretty much top dollar. You couldn't even imagine it going over $1,000" an acre, he said. "Now it's over $3,000."

Brent Qualey has been in the farm real estate business for 27 years and is currently a broker and vice president of Botsford & Qualey Land Co., a real estate appraisal and sales firm with five offices in North Dakota. This past spring, 160 acres of prime farmland came up for sale near Grafton in the northeastern corner of the state. The company was expecting the winning bid to fetch somewhere in the low-$4,000 range per acre, Qualey said.

At the public auction, "there were 10 very interested buyers," Qualey said. "It was a good old-fashioned bidding war." The winning bid was for about $5,800 an acre. Qualey said there is "no doubt" that such oh-my-gosh sales are more common now. Interviewed in late April, he said, "The market has changed dramatically in the last six months," rising by 20 percent on top of a year-over-year increase of 10 percent. Like a tractor with no driver, the value of farmland is doing things no one could have predicted at the start of this decade, because at the time farm prices and income were low, and the outlook was not particularly upbeat for things to change dramatically. Still, farmland was one of the few things farmers could take some financial solace in at the time because it continued to appreciate modestly.

But since about 2001, it's been something else entirely, with farmland seeing steady, double-digit annual increases. There's a lot of conjecture about the source, but most observers agree that rising farmland prices in the first half of the decade were driven mostly by nonproduction factors, like surging housing demand and a strong market for hunting and other recreational land. Capital gains tax laws also played a key role.

But starting about 2006, some of those factors started fading at the same time that the farm economy went on steroids. A confluence of agricultural supply and demand factors has pushed commodity prices up significantly, taking farm income and land values to levels never before seen, or rarely even dreamed. The market for farmland is so hot that the "b-word" has started to enter the conversation.

"Is this a real estate bubble, or has the economic climate changed so dramatically that there is a sustainable price increase?" asked Roger Cramer, senior vice president of risk management for Northwest Farm Credit Services, which is part of the congressionally chartered Farm Credit System. Headquartered in Spokane, Wash., Northwest FCS covers a five-state region and has 12 offices in Montana. Cramer didn't answer his rhetorical question directly, but added, "Something unusual is at work here, and we don't want to make a mistake in the uncertainty."

Ultimately, this is a story about the entire farm economy, not just the land that grows the food we eat. Many, many factors affect the demand for land and, by extension, the things that are produced from it. But land is among the most precious of ag commodities because, as farmers say, nobody's making more of it these days. As such, farmland offers a unique lens for examining broader trends in agriculture.

That's why, in the midst of the most upbeat ag sector in decades, some are starting to worry whether high land prices are sustainable. Despite high commodity prices, robust farm income and strong balance sheets, dangers like high production costs have many nervous about farm profitability. Wounds from the 1980s farm crisis and the crash in land prices are still fresh in many people's minds.

Whether the current farm environment is setting itself up to repeat ag history is impossible to predict. There are eerie similarities between the 1980s and today. But there are also many fundamental differences from the last farm crisis, maybe none as important as the vivid collective memory of the gut-punch suffered by the farm sector 25 years ago. Farmers are also in a stronger financial position today than they were in the 1980s. But not everyone is taking a conservative approach, and those who fail to heed history might be destined to receive a first-hand lesson in hard knocks.

Get it while it's hot

Land prices of late have been like the morning sun; it's a pretty safe bet that both are going up.

Land values vary widely across the district, from $60,000 for an average acre of nonirrigated cropland in Hennepin County (home to Minneapolis) to $300 in Custer County, Mont. Most of that gap is due to the relative demand for alternative uses of available land. As farmers know, the most profitable crop any land can grow is houses.

There is much less disparity among counties when it comes to growth in farmland value, whatever its nominal value. From 2001 to 2007, farmland in all 303 counties in the district saw growth, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the vast majority saw strong growth. How strong? In this short six-year span, half saw cropland appreciate by 100 percent or more; almost one in five counties saw increases of at least 150 percent. The fastest-appreciating counties were mostly in Minnesota, the eastern half of the Dakotas and western Montana (see district map in the PDF file).

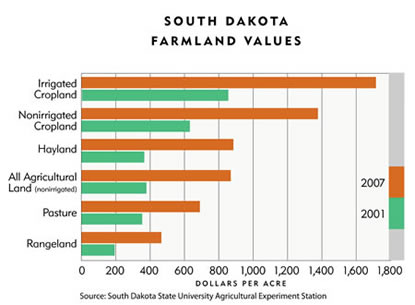

And it's not just cropland. In South Dakota, for example, the value of every major type of ag land more than doubled from 2001 to 2007, save for pastureland, which went up "only" 96 percent (see Chart 1), according to an annual farm real estate survey by South Dakota State University.

Chart 1

Farmers also rent a lot of land. After cropland rental rates lagged for much of this decade, anecdotes and other evidence suggest that they are now playing catch-up. (See more detailed discussion on rental trends.)

A lot of factors are in play when it comes to farmland values. But the fact that crop and livestock prices have been both good and bad over this period—while farmland has consistently appreciated—suggests something besides agricultural production is driving up farmland prices, or at least helping. According to available data and contact with upward of three dozen farming, banking, government and real estate sources, there appears to be a two-stage driver behind farmland appreciation.

In the first half of this decade, farmland appreciated mostly for reasons unrelated to farming; that is, value from ag production played a comparatively static role. More important during this period was demand for open land for nonfarm purposes—in many cases, to build homes during the recent housing boom. But even comparatively rural areas saw secondary demand for farmland, often from investors seeking to diversify their holdings or for recreational purposes like hunting.

"Access to land for hunting purposes is definitely playing a role in farmland prices," said Jeffrey Missling, executive vice president of the North Dakota Farm Bureau (NDFB), in an e-mail. Much of the demand is coming from big-city residents who "want to buy their own little piece of paradise," Missling added.

Equally important, tax laws that allow land sellers to defer capital gains taxes appear to have played a significant role in reinvesting those gains in land elsewhere (see "Swap meet").

To market, to market

But the market entered another phase around 2006. Farmland prices continued their inexorable rise, but the main driver changed. That year demand for housing started to slow, which under more normal circumstances would have likely dampened demand for farmland.

Almost on cue, the ag sector awoke; supply and demand factors began piling up that have put a charge into almost every commodity grown, particularly in the Midwest and Great Plains. Worldwide demand for crops is growing, in part because people in developing countries are eating more meat (which requires significantly more net grain production) as their living standards rise. The push for biofuels—and especially corn-based ethanol—has also introduced an entirely new and large source of demand, mostly within the past five years. This year, ethanol plants are expected to consume between 20 percent and 25 percent of the entire U.S. corn crop, and the USDA believes it might hit 30 percent by 2010.

At the same time, droughts and other problems have strangled farm output in some major producing countries, like Australia. A weak dollar, which makes U.S. goods cheaper to buy, has also fueled a surge in U.S. farm exports. The USDA predicts that such exports will reach a record $101 billion this year—almost $40 billion more than in 2005. Coupled with growing demand, the USDA is predicting that domestic wheat stocks will dip below 300 million bushels this year—the lowest domestic level in 60 years. Wheat stocks worldwide have gone from about 7 billion bushels in 2001 to 4 billion in 2007.

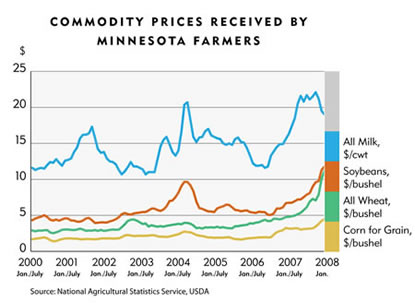

Thanks to a confluence of these and other factors, major commodities produced in the district—like corn, soybeans, wheat and milk—have commanded prices that farmers will talk about for years (see Chart 2). Specialty crops such as lentils, dry edible beans and peas, flaxseed, sunflowers and safflower—all of which have a significant presence in the district—also saw strong prices in 2007. Said one Minnesota farmer, "There's potential in just about anything if you can grow a crop."

Chart 2

For some crops, prices might be more accurately called giddy. As recently as 2005, a bushel of wheat was fetching about $3.60 in Montana. By 2006 it was up to $4.60, and last year the average price was $7.60, according to the USDA. Little did anyone know this was just a warmup. Earlier this year, spot shortages for certain wheat varieties pushed prices on the Minneapolis Grain Exchange to $20 a bushel, and for the year they appear to be settling around $10 a bushel.

Dean Folkvord is general manager and CEO of Wheat Montana Farms and Bakery, an operation that harvests 12,000 acres of wheat, grinds and sells its own flour, and runs a bakery and a handful of deli-cafes. (Folkvord is also a member of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank's Helena Branch board of directors.) He said that his company doesn't often sell wheat into the open market because he needs it for flour customers as well as for the bakery and cafes. But when wheat prices cracked $20 a bushel, "We thought about taking a load of wheat to town in a truck and coming back with a better truck."

Farm bling

Those prices have translated into big jumps in farm income. Nationwide, net farm income skyrocketed from $59 billion in 2006 to $89 billion last year, according to the USDA. This year, it is expected to nudge up further to $92 billion. The last two quarterly agricultural credit surveys of banks by the Minneapolis Fed found that almost 90 percent reported higher producer income compared to a year earlier.

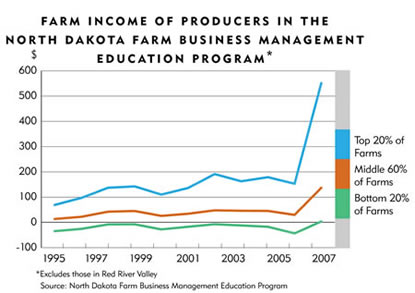

In North Dakota, the profit of crop farms "was astounding" in 2007, according to Andrew Swenson, an extension farm management specialist at North Dakota State University. NDSU helps manage data for the Farm Business Management Education Program. Formally operated by the state Department of Career and Technical Education, FBME gives operators of more than 500 farms—which tend to be larger, commercial scale farms—specialized assistance on their operations in exchange for regularly reporting financial and other data.

Last year, farmers in the program earned profits you might think are a misprint: Average annual income more than tripled its previous best going back to 1989, according to the program's annual report, and farmers at all profit levels greatly improved their performance (see Chart 3).

Chart 3

That gravy train is likely to continue for at least this year. A USDA forecast on farm income noted that 2008 was "projected to be an exceptional year for U.S. crop producers, particularly of feed crops, oil seeds and food grains"—which just happens to be the agricultural sweet spot in the Ninth District, particularly if you add in milk, which is also seeing strong prices.

This brings us back to the land. With cash in hand, today many farmers are aggressively seeking more land, according to numerous sources and anecdotes (no recent data exist on land purchasers or landowner occupation). Scott VanderWal is the third generation to run his family's farm in Volga, on the very eastern side of South Dakota, raising corn and soybeans and running a custom beef feedlot. He's also president of the South Dakota Farm Bureau.

VanderWal said that many of the high sales in his region involved at least one farmer bidding to the end or making the purchase. Oftentimes, it's a close neighbor "who always had his eye on that land and felt that the opportunity may never come again in his career."

Qualey, the North Dakota real estate appraiser, estimated that 30 percent to 40 percent of farmers are paying cash for new parcels; 10 percent is about average, he said. "Today, the farmer is a much more competitive buyer."

Qualey said high crop prices were the main driver, but there were other contributors, including low interest rates, which played a two-pronged role. Those needing to finance land purchases could do so relatively cheaply; on the flip side, the resulting low yields on certificates of deposit—a common savings vehicle for conservative farmers—have pushed some to look to the land for better returns. "You're seeing old farmers pulling money out of CDs and putting it into a piece of land," Qualey said.

Newfound purchasing power among farmers, combined with demand from nonfarm buyers, has many talking about sustainability and whether farmers are setting themselves up for financial ruin. Thomas Anderson is the Farm Service Agency (FSA) director in Redwood County, in the southwestern part of Minnesota. He said via e-mail that a 160-acre parcel recently brought $5,600 an acre in a nearby county. "I thought when land got to $2,500 it could not be sustained."

Missling, from the NDFB, pointed out that prudent farmers determine the appropriate price for land by calculating production costs and making adjustments for things like location, yield capacity, soil type and property taxes.

"I think where a lot of people run into trouble is, they go off-script and lose sight of simple economics," said Missling, adding that land values were appreciating at a rate that "appears to be a bit too aggressive, in my humble opinion, given the fact that there is no certainty of where commodity prices are going."

But some are weighing high acquisition costs against the profitability and debt capacity of their entire farm operation—in essence, rationalizing that they can afford to pay a premium for land given the premium they are receiving for crops, even if it's short-lived.

Paul Lautenschlager manages Beach Cooperative Grain Co., a grain elevator in Beach, N.D. In an e-mail, he pointed out that land costs are "relatively cheap if you look at the long run. The cost of land spread out 30 years is the smallest input cost per acre the farmer has" compared with seed, fertilizer, fuel and transportation costs.

Indeed, the debt and cash flow argument is moot where farmers are paying cash on the barrelhead for more land. "Back in the '50s it was said you could pay for the land you bought with one crop," Lautenschlager said. "With today's high commodity prices you can do the same, even with high land prices."

Farm vertigo

But truth be told, there are a lot of Nervous Nellies in farm country. Indeed, not everyone in agriculture is benefiting from high land or crop prices (see "Outside the winner's circle"). Even for crop farmers, high commodity prices and strong income are not enough to blow away some very gray clouds on the farm horizon.

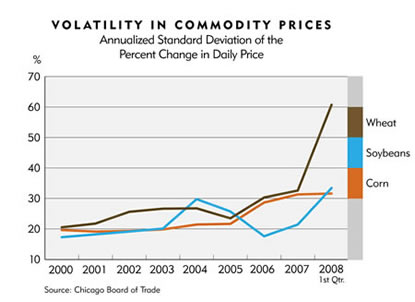

Volatility has always been a part of farmers' lives, thanks to the ruthlessness of Mother Nature. But ag markets are seeing more volatility these days. For example, average price swings for commodities have grown wider—in some cases, much wider—in recent years for corn, wheat and soybeans, according to data from the Chicago Board of Trade (see Chart 4).

Chart 4

More uncertainty has come to futures markets as well. Typically, as a futures contract nears its expiration date, the price of that contract converges with the prevailing cash price. There can be some separation—called the basis—between the two final prices, but it's usually very small. But in the past few years, basis spreads have widened and become less predictable.

At an April public hearing on these matters, Bob Stallman, president of the American Farm Bureau Federation, told a federal regulatory body that the lack of both convergence and reasonable expectations regarding basis "is significantly increasing the risk faced by producers."

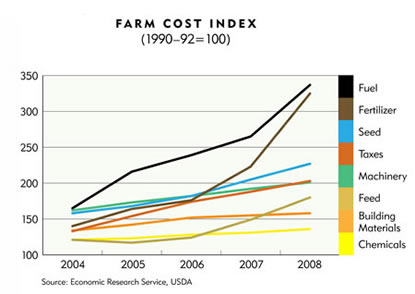

Even higher on the list of farm concerns is the rapidly rising cost of production, which has been chasing rising crop prices like a shadow. USDA figures show that prices paid by farmers for inputs—machinery, fertilizer and other things needed to grow a crop—increased moderately up until about 2006. But over the past two years, costs for many inputs have been soaring (see Chart 5). Fertilizer costs have doubled—and that's for the lucky farmers. Shortages have meant that some are doing without, or paying even larger increases; others are reportedly buying fertilizer for the 2009 growing season in an effort to outrun anticipated price hikes.

Chart 5

Rising input costs can be traced to a variety of factors. Seed costs are going up thanks to increased plantings, and the sky-high price of diesel fuel is pushing up the cost of running farm machinery. Fertilizer, on the other hand, is a little more complex. Along with rising use, both in the United States and worldwide, fertilizer gets a multi-whammy from high fuel costs. For example, prices are rising for natural gas, a central ingredient in fertilizer. Much of the world's fertilizer is also produced elsewhere, and its bulky nature makes it expensive to ship. A weak dollar pushes importation costs higher still.

In 2007, raising an acre of corn in much of the district typically cost between $350 and $400. With an average yield, that works out to a cost of roughly $2.50 to $3 per bushel produced. For soybeans, some cost estimates ran as high as $7 per bushel, and wheat between $4 and $4.50 a bushel, according to an analysis by Ag Lender, a farm-finance publication. Not long ago, farmers were happy to get those prices for their harvests.

As a result, there's more anxiety in today's farm sector, "and it's on the input side," said Jim Boerboom, deputy commissioner for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. Input costs "were very stable for years. But now you can't even set a budget for it. It's that uncertainty" that has farmers looking over their shoulders.

And while current prices still offer farmers a good margin, many observers are quick to offer two related caveats: First, they don't expect high commodity prices to hold long, and second, input costs won't come down as fast.

Like many others, VanderWal, the South Dakota farmer, assumed that lower crop prices were not a matter of if, but when. "We have a narrow window where revenue will be significantly greater than expenses, and then the margins will quickly narrow again." He said a lot of profit tends to go back into land expansion, either as purchases or rent. "So, at some time in the future, our sale prices will fall back, but expenses will not, and we will have a huge profitability problem."

Back to the future?

Farming has always been a capital-intensive, high-risk endeavor. Yet virtually every significant financial element that a farmer uses to plan a business—capital costs, production inputs, output prices—is in uncharted territory and seeing greater volatility today. And many think the old "bet the farm" analogy is starting to sound a little too real.

Kelly Cape, head of the Day County (S.D.) FSA office, has been involved in ag finance for 25 years. Despite a "huge" profit opportunity, "the current situation is very unsettling due to the amount of risk everybody is taking," said Cape, via e-mail. A sudden drop in crop prices or lower yields "has the risk of some operations losing a tremendous amount of money."

And it doesn't take an ag historian to remember the last farm crisis, when a similar scenario played out over the course of about a decade. It got started in the latter half of the 1970s; commodity prices and farm income were strong, fueling a surge in land values. Farmers leveraged this rising paper wealth to take on more debt to expand operations. Then in the early 1980s, the farm economy went soft. Low commodity prices and high interest rates sent land values into the manure lagoon, and farmers quickly found themselves underwater financially. Farm bankruptcies were rampant, and almost 200 ag banks failed in the latter half of that decade.

Many acknowledge that they can see—indeed, feel—the speculative similarities to the 1980s. Qualey, the appraiser, got his start in the profession in 1981, on the cusp of a farm crisis. "I saw things slip for six years. So I was indoctrinated at a very interesting time," he said. "We still see some things that are reminiscent of the 1980s," including some aggressive buyers who believe "that land prices can't go down, they can only go up."

But Qualey and many others also believe the current situation has important differences from the 1980s. Qualey said there was "no doubt" that farmers today are not leveraging their assets as much to buy land. "That's the one big difference. In the 1980s, leverage was the key. Today we are not seeing that, and lenders are being more responsible." Most banks are requiring 30 percent to 35 percent cash equity to finance a parcel, he said. "There's no 100 percent (debt) loans like we saw in the 1980s."

Everson, from the SDBA, said he attended an ag bankers conference in the spring with about 140 participants. There and elsewhere, "what I keep hearing is that there are enough of them around from the 1980s, and they are not interested in lending based on asset levels" this time around. Though crop prices are attractive, "they've all seen commodity prices come down as fast as they go up." As a result, bankers are making sure that farms have adequate cash flow given high land and input costs.

There are other simple, but critical differences today, like much lower interest rates that reduce debt loads. Farmers also have more risk management tools at their disposal (see "Hedging their bets"). Even the ubiquity of personal computers means that bankers and farmers alike have access to more timely and relevant information regarding supply and demand factors. "Everybody's a lot more aware of what's going on," Everson said.

Some banks are raising the hurdles for farm borrowers. Northwest Farm Credit, for example, typically requires 60 percent to 70 percent loan-to-collateral rates. But starting this past April, according to Cramer, it began using a collateral formula that discounts a portion of increase in land value from the previous 24 months because "the last two years have seen fairly extraordinary gains," Cramer said. "You really have to analyze that repayment capacity under different scenarios."

Other banks also appear to be making some adjustments. In this year's first quarter survey of ag credit conditions by the Minneapolis Fed, about 10 percent of the lenders reported increased collateral requirements.

The same, but different, and better

Opinions vary on the level of farm pain should crop or land prices fall. VanderWal believes "another washout" is possible, where overleveraged producers will not make it. "Bottom line, we need to get debt paid down quickly and get more streamlined and efficient than ever before."

In fact, a fair amount of financial data suggest that this is happening and that things just might—might, mind you—be different this time.

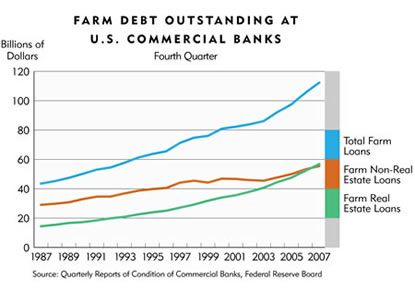

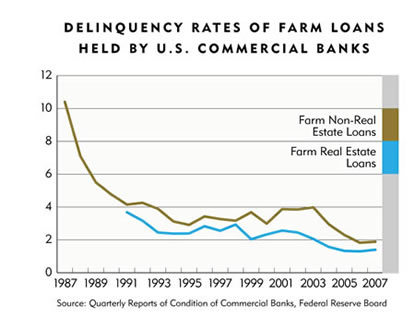

For starters, producers have not mortgaged the farm to get in on the boom. Yes, farm debt has increased: From 2000 to 2007 (fourth quarter of each year), total farm debt at commercial banks nationwide increased at an annual compound rate of close to 5 percent, according to the Federal Reserve's quarterly reports of ag conditions at commercial banks (see Chart 6). Real estate debt grew much faster over this period, but was offset by comparatively slow growth in operating and other farm loans. Over the same period, farm income grew at a compound rate of more than 8 percent, and farmers' delinquency rates for both land and operating loans are at their lowest levels in roughly three decades, possibly longer (see Chart 7).

Chart 6

Chart 7

Other evidence shows that farmers are building equity the old-fashioned way by paying off debt faster. According to the Minneapolis Fed's ag credit survey, 54 percent of ag banks in the district reported higher loan repayments in the fourth quarter of 2007, easily the survey's highest level since the question was included in 2001; then in the first quarter of 2008, that rate went higher still, to 60 percent.

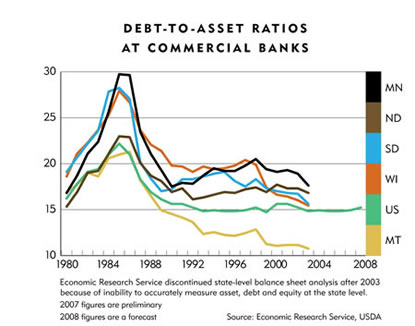

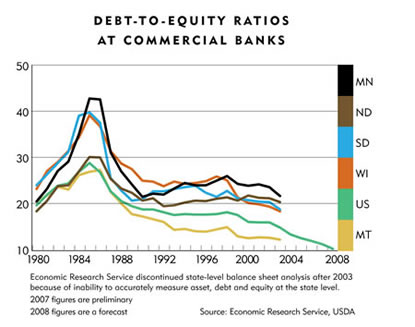

When you consider both historical data and a bin full of anecdotes, it appears that farmers, as a group, are in better financial position to weather a downturn in land values, the ag economy or both. The balance sheets of farms nationwide and in the district show modest debt levels and very strong asset and equity levels. Commonly used measures of financial health, like ratios of farm debt to both assets and equity, are at their best levels in at least three decades (see Charts 8 and 9).

Chart 8

Chart 9

Of course, one reason for stronger balance sheets over time brings us back to the beginning: high—and potentially speculative—land prices. But farmers don't appear to be quite the paper tigers they were back in the 1980s.

Over the past dozen years, for example, Minnesota farms enrolled with the Center for Farm Financial Management (run by the University of Minnesota) saw their average real net worth increase by $360,000. According to program reports, only 24 percent was the result of asset appreciation; the remaining three-quarters came from "retained accumulated earnings." In other words, farmers—at least in this program—have been saving for that rainy day when prices, and possibly land values, fall.

Indeed, a fair number of sources said they expected land prices to decline, but some—even many—farmers could weather such an event.

"Deep down there is that sense" that land prices will decline, said Everson. "But the question is, ‘When and how far?' A nominal change, like 10 percent, I can't imagine that's going to have a real substantial impact on lenders and producers." Even a drop of 25 percent might only catch "some guys" that weren't managing their business well, he said. That's where Everson stopped. "I can't imagine you'll have a shakeout like you did 25 years ago."

Jerry Fast, a senior vice president at Profinium Financial in Fairmont, Minn., has been an ag banker and part-time farmer for 27 years. He said via e-mail that land sales there were averaging around $4,000 per crop acre last October. He estimated that land can drop back to $2,400 an acre "before most farmers or investors would be pinched by their lenders to sell or consider walking away."

Will there be blood?

As farmers like to say, $5 corn and $10 wheat are only good when you're unloading the truck. The point is that risks abound. Already, a wet, cold spring delayed crop plantings throughout most of the district, and severe rain in June flooded fields across the Midwest. At the same time, much of the western Dakotas and eastern Montana suffer from drought or droughtlike conditions; all of these weather patterns could seriously harm yields and profitability.

So there is always potential for pain in the ag sector. Most people in the farm community understand that strong land prices and high commodity prices—while a godsend—also create an environment ripe for disaster because ag markets are prone to boom and bust cycles.

Missling, from the North Dakota Farm Bureau, has worked both sides of the corn row, being born and raised on a farm in southwestern Minnesota and having worked formerly as a county extension agent before coming to NDFB. "I certainly hope producers are keeping their heads screwed on straight when it comes to valuing their land on a balance sheet. … It wouldn't surprise me to see some inflated numbers."

He added said that anyone in agriculture "should understand the complexities of market cycles. … Like any industry, agriculture is not immune to a day of reckoning. What goes up, must come down. Just like the stock market, there will inevitably be periods of correction. The folks who bought land responsibly and who lived within their means will be fine. The others won't be."

Daniel Rozycki, a Minneapolis Federal Reserve associate economist, and Clint Pecenka, research assistant, contributed to these articles.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.