Abstract

Banks are vulnerable to self-fulfilling panics because their liabilities (such as demand deposits and certificates of deposit) are short term and unconditional, and their assets (such as mortgages and business loans) are long term and illiquid. To prevent wider financial fallout from such panics, governments have strong incentive to bail out bank debtholders. Paradoxically, expectations of such bailouts can lead financial systems to rely excessively—from a societal perspective—on short-term debt to fund long-term assets. Fragile banking systems thus impose external costs, and regulation may therefore be socially desirable.

In light of this fragility and cost, we examine two of the major theoretical benefits from the reliance of the banking system on short-term debt: (1) maturity transformation and (2) efficient monitoring of bank managers. We argue that while both justifications may be compelling, they point us to financial regulations very different from the ones currently in place. These theoretical justifications suggest that the assets funded by banks should not have close substitutes in publicly traded markets, as is currently the case.

Introduction1

The enormous direct and indirect costs of rescuing banks and related financial institutions during the financial crisis of 2007-08 generated widespread policy debate on future banking regulation, resulting in part in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. Largely absent from these discussions was a careful reexamination of the services that banks provide and whether they are sufficient justification for the inherent financial fragilities of banks and the societal costs of this fragility.

The inherent fragility of banks

In what sense are banks and similar financial institutions fragile? Answering this question requires understanding the balance sheets of financial institutions more generally. The assets of financial institutions are, by and large, financial assets, and claims on them are primarily financial liabilities. They hold few tangible assets such as land, buildings or machinery. Their financial assets consist mainly of promises to deliver dollars at future dates (and perhaps then only under certain circumstances). Among such assets are stocks, bonds and the notes on mortgages and business and consumer loans, as well as an array of more exotic financial instruments such as derivatives. Likewise, their financial liabilities consist mostly of a variety of obligations to deliver dollars at particular dates, under certain circumstances.

Some types of financial institutions, particularly banks, have liabilities that are mostly short term and unconditional. For example, banks issue demand deposits, which promise to pay a fixed amount of money whenever a depositor demands a withdrawal. Likewise, banks issue certificates of deposit (CDs), which promise to pay a fixed amount of money at a particular (usually very near-term) date. Typically, banks rely on the rolling over of CDs, when they mature, into new CDs. In this sense, a failure to roll over a short-term CD can be thought of as equivalent to a withdrawal from a deposit account.

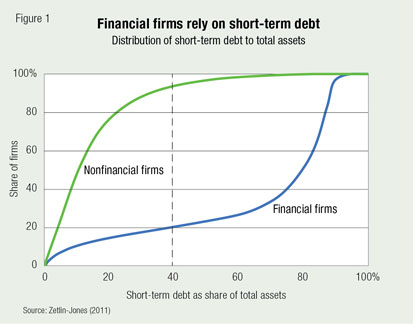

In Figure 1, we display the distribution of firms—financial and nonfinancial—by their ratio of short-term debt to total assets, for all publicly traded companies. This figure shows that financial firms typically have much higher levels of short-term debt relative to total assets than nonfinancial firms. For example, 80 percent of financial firms have a ratio of short-term debt to total assets greater than 40 percent, while only 10 percent of nonfinancial firms do (see vertical dashed line).

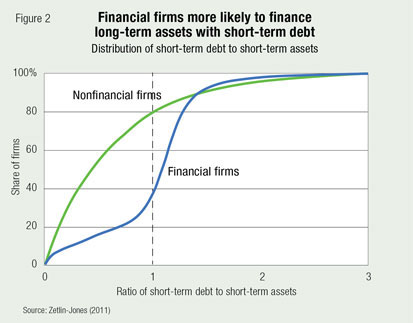

In Figure 2, we display the distribution of firms by their ratio of short-term debt to short-term assets, again for all publicly traded financial and nonfinancial firms. Firms that have ratios greater than 1 are using short-term debt to finance holdings of long-term assets. The figure shows that nonfinancial firms are far less likely than financial firms to use short-term debt to finance their holdings of long-term assets—less than 20 percent of nonfinancial firms depend on short-term debt, while roughly 60 percent of financial firms do so.

The bulk of these financial firms with high levels of short-term debt are legally structured as banks. From an economic standpoint, the financial firms we focus on in this policy paper are those with high levels of short-term debt, and for convenience we’ll refer to them all as banks.

This reliance on short-term debt makes banks fragile in the sense that they are particularly vulnerable to the risks of insolvency and the possibility of confidence crises. Since bank assets are usually much longer term than their liabilities and since the value of these assets fluctuates, a bank’s net worth (its assets less its liabilities) also fluctuates a great deal.

Furthermore, a bank’s assets are typically illiquid. A bank cannot easily and quickly sell its portfolio of small business loans, home equity loans or jumbo mortgages, for instance, to satisfy an unexpected surge of withdrawals from demand deposit accounts. The illiquidity of banks’ assets and the demandable structure of their liabilities thus expose banks to crises of confidence. Since a bank typically will not be able to meet the demands of all depositors within a short period of time should they all choose to withdraw, banks are vulnerable to self-fulfilling panics in which depositors withdraw their funds simply because they believe other depositors will do so.

This panic is an entirely rational response even if the bank is solvent (though illiquid). If a depositor suspects that other depositors will withdraw their funds in the near future, it is rational for that depositor to rush to the bank and withdraw his or her deposits before other depositors can do so. But since this logic holds for all depositors, banks are subject to self-fulfilling panics in which the belief in a run causes the run.

In the midst of such self-fulfilling panics, governments have a strong incentive to intervene to bail out debt holders of banks in order to prevent the entire financial system from failing. Paradoxically, expectations of such bailouts can increase the incidence and depth of financial crises because once depositors believe that their deposits will be protected by general tax revenues in the event of potential systemic failure, they have less incentive to monitor the risk-taking proclivities of bank managers.

Bank managers, in turn, have increased incentive to take on risk, knowing their failures are implicitly insured—taxpayers (not banks themselves) bear the full consequences of this risk-taking. Given that the banking system rationally chooses to take on risk, the possibility of insolvency of the banking system increases, and the need for bailouts rises.

In this way, expectations of bailouts can lead financial systems to rely excessively—from a societal perspective—on short-term debt to fund long-term assets. Fragile banking systems thus impose external costs, and regulation may therefore be socially desirable.

The benefits of banks

Why then do we allow banks—financial institutions that fund long-term assets with short-term debt—to operate? One answer is historical: The very ubiquity of banks throughout history suggests that they serve a valuable function. But the world has much changed since the invention of banks. In particular, the range of economic activities that can be funded through publicly traded assets has expanded enormously. For instance, in the not-too-distant past, publicly traded mortgage-backed securities did not exist. In light of these changing circumstances, it is worth examining how long-term assets should be funded and the role banks should play in funding such assets.

Given that we have already discussed the weaknesses or costs of such financial institutions, we’ll now use economic theory to examine the possible social benefits of having a financial system in which illiquid assets with volatile values are funded by demand deposits and short-term debt. This cost-benefit analysis allows us to ask how modern economic theory can be used to design better regulatory systems for banks. This issue is clearly of pressing importance given the central role that banks are argued to have played during the recent financial crisis. This issue is also of central importance given the importance of banks to financial systems throughout the world.

We examine the role of banks and the role of regulation by considering, in turn, two of the major theoretical justifications for the reliance of the banking system on short-term debt:

- Demand deposits allow banks to engage in socially useful maturity transformation.

- Demand deposits allow for efficient monitoring of bank managers.

We argue that while both justifications may be compelling, they point us to financial regulations very different from the ones currently in place. Specifically, they suggest that while it may be important to have institutions that finance long-term assets with short-term debt, the assets that are so funded should not have close substitutes in publicly traded markets.

Our logic is as follows: The economic case for regulating such institutions at all is due to the external costs they impose. But any such regulation should also, to the extent possible, preserve the benefits that economic theory suggests they convey. We argue that these benefits exist only when these institutions hold assets which do not have close substitutes that are traded in public markets. Indeed, our analysis suggests that bank assets having close publicly traded substitutes destroys the possible social benefit of banks under the maturity transformation view and reveals the social benefit to be zero (or small) under the efficient monitoring view. Thus, institutions that issue short-term debt should be allowed to hold only a limited amount of publicly traded assets.

Theoretical justifications of banking

We now provide closer consideration of the two primary theoretical justifications for a banking system that relies on short-term debt. We first describe and then assess the maturity transformation rationale, and then we turn to the notion that demand deposits permit efficient monitoring of bank managers, again starting with a description followed by our assessment.

Maturity transformation

Banks are often said to perform a miracle of financial alchemy referred to as maturity transformation. They are thought to hold long-term assets that yield a high rate of return and finance these assets with short-term claims (such as deposits) that pay a higher rate of return than what those depositors could earn if they invested directly in short-term assets (such as very short-term bonds).

Such a form of financial alchemy implies that those who roll over their short-term claims until the maturity of the long-term asset will necessarily receive a lower rate of return than if they had directly held the long-term asset. In effect, maturity transformation is a redistribution of resources from those who roll over their short-term claims to those who redeem such short-term claims early. Why would this financial alchemy be socially desirable?

Diamond and Dybvig (1983) developed a model in which such maturity transformation is desirable and possible. Furthermore, they showed that the arrangement that delivers such maturity transformation resembles banks in the sense that (at least conceptually) households get access to their funds whenever they want to, so that the liabilities of banks resemble demand deposits, while the assets of banks are long term and illiquid. (See Appendix A-1 for a simplified technical description of the model.) The basic idea in their model is that the redistribution of resources associated with maturity transformation is desirable because such redistribution allows for insurance. If people are not sure whether they will need resources only at the maturity of long-term assets or at a date prior to maturity, they may wish to insure themselves by accepting a lower return at maturity in exchange for a higher return should they instead desire their funds sooner.

An assessment of the maturity transformation view

While Diamond and Dybvig’s model provides important insights into the possibility of maturity transformation, the mechanism rests on an increasingly implausible feature of the model: nonbank financial institutions do not also hold assets such as the mortgages and mortgage-backed securities typically held by banks as part of their transformation role [a point originally made by Jacklin (1987)]. Put simply, if it is possible for households to hold the long-term assets of banks outside the banking system, the ability of banks to perform maturity transformation is destroyed, along with the social benefit from doing so. (For technical discussion of this point, see Appendix A-2.)

As we show in Appendix A-2, if people can hold long-maturity assets outside the banking system, they have strong incentives to do so. If they happen to not need funds prior to maturity, they can obtain higher returns than under maturity transformation since they are not subsidizing those who need their funds sooner. If they happen to need their funds sooner, they can simply sell their holdings of these long-term assets to customers of the banking system who do not need their funds until maturity. Further, these customers will be willing to sell to them. Recall that such bank customers were promised relatively low returns for funds held long term inside the banking system and relatively high returns if they needed their funds earlier. But for these customers, the event they were insuring against—that they would need their funds early—did not occur. After they know this, they have strong incentives to trade with those outside the banking system in order to achieve higher returns. Analysis of the Diamond-Dybvig model under this alternative assumption—that the assets typically held by banks are also traded in public markets—demonstrates that banks cannot provide the social benefit associated with maturity transformation.

Recent data on holdings of U.S. financial institutions show that, indeed, market trading of such assets is increasingly common.

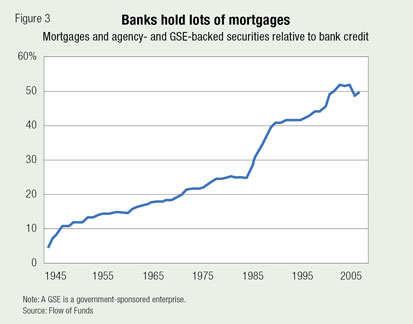

Figure 3 shows mortgages and mortgage-backed securities held by bank and bank-like entities in the United States relative to their stock of financial assets (typically known as bank credit). Note that such assets constitute almost 50 percent of bank financial assets over the past decade.

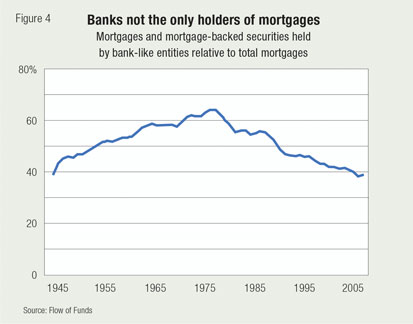

Figure 4 shows the total outstanding stock of mortgages and mortgage-backed securities held by banks and bank-like entities relative to the total stock of mortgages. Note that these banks and bank-like entities hold only about 40 percent of the total outstanding stock of mortgages over the past decade, and that share has declined steadily since the late 1970s. That is, institutions that are very different from banks now hold a very significant and rising share of the total outstanding stock of mortgages. Such institutions do not fund their assets with short-term debt.

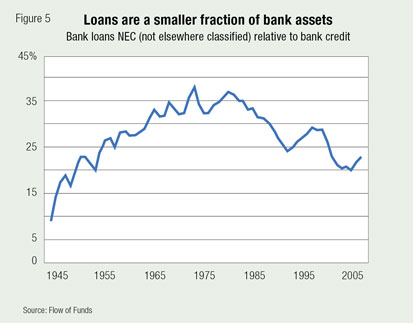

In this sense, the ability of banks to achieve maturity transormation is severely limited by the holdings of close substitutes by other institutions. Figure 5 shows bank loans for commercial and industrial purposes relative to the stock of financial assets (again, typically known as bank credit) held by banks. Such bank loans may well not have close publicly traded substitutes. But they also make up only one-quarter of bank assets. This perspective suggests that if we view maturity transformation as the principal reason for the existence of banks, the United States could do very well with a banking sector just a quarter the size it now is.

Efficient monitoring

Over the past 25 years, a theoretical literature has emerged arguing that short-term debt and the associated possible runs on financial institutions may in fact be an efficient way of allowing markets to incorporate information that investors have about returns on financial assets. [See Chari and Jagannathan (1988), Calomiris and Kahn (1991), Diamond and Rajan (2001) and Zetlin-Jones (2011).]

The basic idea is that some investors often have access to information about the returns on financial assets and that this information is valuable to other investors and financial markets as a whole. Efficient arrangements will then have to provide such investors with incentives to obtain and act on this information, and those incentives may require market mechanisms that provide higher returns to those investors compared with others. These differential returns can be efficiently provided through “bank runs” in which early withdrawers (“sophisticated” investors who have relevant information through their close monitoring of managers) get higher returns than late (“uninformed”) withdrawers. [See Appendix A-3 for a simplified technical discussion, using the Calomiris-Kahn model (1991).]

One way of implementing the efficient arrangement outlined above is to think of assets being provided and being funded by demand deposits. The demand deposits allow all investors to withdraw their assets at will. In normal times (when sophisticated investors receive favorable signals about the bank’s returns), all investors wait to withdraw their assets at maturity and receive the same return. In crisis times (when sophisticated investors get unfavorable signals), large withdrawals occur. Those who choose to withdraw early receive a higher rate of return than those who wait until maturity. The observation that investors who withdraw early get a higher return resembles a bank run and therefore creates a crisis for the bank.

An assessment of the efficient monitoring view

The efficient monitoring view of the social usefulness of banks rests crucially on the idea that it is difficult to set up alternative methods of compensating sophisticated investors and/or efficient managers. But, in fact, this assumption may be unrealistic. For example, one could easily imagine various kinds of equity claims as well as combinations of equity and debt that could provide sophisticated investors with appropriate incentives to monitor the activities of managers. One could also imagine compensation contracts for managers that are tied to the market valuation of their assets. Such mechanisms are widely used in firms whose claims are traded in public markets.

On the one hand, to the extent that close substitutes to the assets held by banks are traded in public markets, the marginal value of having banks fund these projects as well is likely to be small since these assets would likely be funded by public markets even if banks did not exist. On the other hand, the costs of banks—in the form of crises and their associated bailouts (as well as the changes in bank risk-taking behavior induced by the expectation of bailouts)—are clearly quite large.

In this sense, under both the efficient monitoring and the maturity transformation views, banks provide significant social value only when the assets they hold do not have close substitutes that are traded in public markets. Bank assets having close publicly traded substitutes destroys the possible social benefit of banks under the maturity transformation view and reveals the social benefit to be zero (or small) under the efficient monitoring view.

Finally, the efficient monitoring view also poses a severe challenge to those who view bailouts as necessary for the proper functioning of financial markets. Note that under the efficient monitoring view, crises do occasionally occur, and, at the time of the crisis, if governments were particularly concerned about the well-being of unsophisticated investors, bailouts of all investors would be considered desirable. But if such bailouts are anticipated, sophisticated investors have no incentive to monitor banks when such monitoring is costly. Absent such monitoring, either valuable projects will not be undertaken or, given the expectations of large transfers from the government, inefficient projects will be undertaken.

Implications for policy

To answer the question “Do we need banks?” we first need to answer the question “What are banks?” Guided by the data, we have chosen to think of banks as institutions that hold long-term, illiquid, volatile assets and issue large amounts of short-term debt to finance these assets. Given the possibility of bank crises, this institutional arrangement seems puzzling on the face of it. Nevertheless, we need to take seriously the observation that such institutions have been a durable part of the economic landscape for many centuries and, arguably, have played a significant role in the industrial revolutions the world has been fortunate enough to experience.

Both the maturity transformation and the efficient monitoring views suggest that it may desirable to fund long-term assets that have no close substitutes in publicly traded markets with short-term debt. Both views also suggest that the social value of funding long-term assets that have close publicly traded substitutes with short-term debt is small. Given the costs imposed by crises and attendant bailouts, both views suggest that it may be desirable to allow these institutions to issue short-term debt only if their assets do not have close publicly traded substitutes. Otherwise their benefits are either zero or negligible.

These implications suggest policies that are dramatically different from those undertaken by most bank supervisors or various forms of international regulation under the Basel agreements. Current supervisory systems encourage banks to hold assets with close substitutes for publicly traded assets by giving such assets lower risk ratings and by requiring less equity capital to back up these assets. These supervisory systems encourage the banking system to hold publicly traded assets that are risky in the full knowledge that if the returns on these assets are poor, governments will step in to bail out short-term debt holders.

The framework for regulatory policy implied by our analysis would lead to a banking system that is radically different from the one we currently have. Institutions that issue large amounts of short-term debt relative to their assets would be regulated and required to hold relatively little of their assets in publicly traded securities.

This new system would not eliminate all crises. Indeed, we have argued that bank runs may well be an essential ingredient of an efficient economic system. In all likelihood, however, the crises of this new system would be much smaller and less costly than those we have experienced in the recent past. One reason: The volume of assets backed by short-term debt would be dramatically smaller under our proposed system than under the current system.

The economic theories explored in this paper suggest we do need banks. These theories also point us to constructive ways in which we can reform the financial system to make it more efficient and to minimize the spillover costs imposed on the broader economy by crises that affect particular financial institutions.

Endnote

1 The authors thank Narayana Kocherlakota, Dick Todd and Kei-Mu Yi for useful comments and Doug Clement for editorial assistance. V. V. Chari thanks the National Science Foundation for supporting the research that led to this paper.

References

Calomiris, Charles W., and Charles M. Kahn. 1991. The role of demandable debt in structuring optimal banking arrangements. American Economic Review 81 (3): 497–513.

Chari, V. V., and Ravi Jagannathan. 1988. Banking panics, information, and rational expectations equilibrium. Journal of Finance 43 (3): 749–61.

Diamond, Douglas W., and Philip H. Dybvig. 1983. Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. Journal of Political Economy 91 (3): 401–19.

Diamond, Douglas W., and Raghuram G. Rajan. 2001. Liquidity risk, liquidity creation, and financial fragility: A theory of banking. Journal of Political Economy 109 (2): 287–327.

Farhi, Emmanuel, Mikhail Golosov and Aleh Tsyvinski. 2009. A theory of liquidity and regulation of financial intermediation. Review of Economic Studies 76 (3): 973–92.

Jacklin, Charles J. 1987. Demand deposits, trading restrictions, and risk sharing. In Contractual Arrangements for Intertemporal Trade, ed. Edward C. Prescott and Neil Wallace. Vol. 1 of Minnesota Studies in Macroeconomics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wallace, Neil. 1988. Another attempt to explain an illiquid banking system: The Diamond and Dybvig model with sequential service taken seriously. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 12 (Fall): 3–16.

Zetlin-Jones, Ariel. 2011. Efficient financial crises. Working paper. University of Minnesota.