The dozens of lakes and streams on the Lac du Flambeau Indian Reservation in northern Wisconsin form a complex network of aquatic assets that members of the tribe’s natural resources department work diligently to protect. One way of safeguarding the tribe’s water resources is to identify catchment basins that feed rainwater into the system. By ensuring that identified basins are adequately covered in vegetation, which filters pollutants found in runoff, the tribe can help protect the overall health of its watersheds.

The task is made easier through the use of geographic information system (GIS) technology. A GIS is a computer system that enables users to visualize and analyze spatial information. In other words, it allows people to produce data-rich maps that can be used to make informed decisions. Len Fralick, a GIS specialist and roads planner for the Lac du Flambeau tribe, explains that to understand where catchment basins are, the natural resources department creates a map that includes not just lakes, streams, and vegetation but also the elevation and slope of the terrain. Doing this helps the tribe determine the direction of water flow during and after a rain event and, therefore, where catchment basins lie.

“GIS is critical to our efforts here,” he says. “Just about every program we have has a need or purpose for mapping.”

Managing natural resources is just one application of GIS technology. Other common uses include community development and planning, transportation and network analyses, public safety planning, cultural and historic preservation—essentially, anything that can benefit from the tying of data, such as demographic or environmental information, to a point or area on a map. For American Indian tribes, interest in using this technology comes at a time when they face increasingly complicated land-management decisions, including those prompted by a recently implemented federal program that enables tribes to buy back and consolidate privately held reservation land.1/ Once acquired, the land can be used for commercial development, housing, tourism, or whatever long-term purpose a tribe intends. With so much at stake—economic development, cultural preservation, community planning, etc.—the need for an effective land-management tool, such as a GIS, is clear.

“One of our primary uses of GIS is mapping out land ownership,” says Fralick. “We’re using this technology to help us to better understand the conditions on our reservation. Other tribes can do this, too.”

A spectrum of sophistication

Although no definitive figure exists on the number of tribes that use GIS, Garet Couch, president of the National Tribal Geographic Information Support Center, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization with an objective to provide assistance to Native American tribal governments and Native American organizations regarding geographic information technology, believes that nearly 45 percent of the 566 federally recognized tribes use the technology. However, he notes that the sophistication of GIS offices from tribe to tribe “runs the spectrum.”

“Some tribes have multiple, full-time staff who perform wide-ranging GIS services, while others have just a part-time staff person who makes relatively simple maps,” Couch says. Couch would like to see tribes establish the former type of GIS department—self-sufficient, comprehensive shops that support tribes in many of their land-management and community development efforts—but he identifies funding and appropriate staffing as obstacles. To fund GIS activities, tribes often rely on contracting and grants, neither of which is a reliable source over time. And to staff GIS departments, tribes need employees who not only have adequate technical expertise but also institutional knowledge built up over years of work.

“Too often, tribes will lose the only person they have working in GIS,” says Couch, “and that person leaves with all of their contacts and knowledge. When tribes eventually do hire a new GIS technician, it’s almost like they have to build their department from scratch.”

Couch suggests that, if funding permits, tribes hire a community member to shadow the GIS work being done. He or she will then be able to orient new GIS hires to past projects and current administrative practices. Ultimately, he says, tribal leaders need to be aware of the power of GIS technology and devote the resources to deploying it.

Comprehensive curricula

As of summer 2014, about 20 of the 37 native colleges and universities across the country offered coursework in GIS.2/ While the majority of those classes limit the depth of study to introductory material, several colleges have established comprehensive curricula that encompass a range of GIS concepts and methods, from basic to advanced.

One such school is Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College (LCOOCC) near Hayward, Wis. In 2010, it began offering a one-year certificate program in geospatial technology after the demand for its introductory GIS class, which it had been offering since 1996, grew from about one or two students a year to more than a dozen.

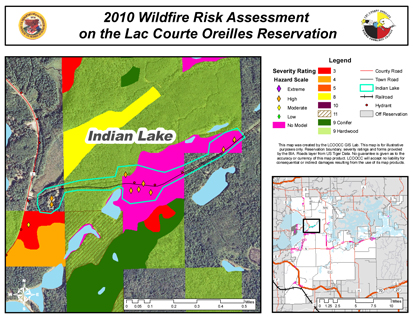

A recent project LCOOCC’s GIS students worked on was a wildland fire-risk assessment of the nearly 400 homes on the Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservation, an analysis that the Fire and Fuels Department of the Great Lakes Agency of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) had contracted with the school to conduct. Over the course of a year, students analyzed aerial imagery, vegetative land cover, fire hydrant locations, and home locations on the heavily forested, 77,000-acre reservation and then presented their results to both the BIA and the tribe’s volunteer fire department.

“In the end, this project benefited many parties: students, government, volunteer fire fighters, and the reservation in general,” says Amber Marlow, LCOOCC extension director, who has taught GIS. She notes that funding for the LCOOCC’s GIS lab and coursework, though unsteady, often comes from contracts with non-tribal government agencies and tribes located near the school. “These are the types of projects that resonate with people learning about GIS.”

Offering tribal members courses in GIS isn’t limited to tribal colleges, however. The BIA’s Office of Trust Services Geospatial Support (OTSGS), a Colorado-based department of the federal government that helps tribes learn about and deploy GIS technology, offers free in-person and online courses to tribal and BIA employees who use GIS software as part of their jobs. According to the department’s program manager, Wyeth “Chad” Wallace, the OTSGS has been offering classes and training for longer than two decades. Moreover, the OTSGS makes available to all federally recognized tribes a suite of GIS products and extensions at no cost. To date, approximately 245 federally recognized tribes have taken advantage of this free service, and more than 4,000 tribal workers have registered with the OTSGS as users of GIS.3/

“We’re seeing a lot of interest from tribes that want to use GIS as a tool to help manage their lands,” says Wallace, “but we’d like to see even more.”

An everyday tool

For the many tribes that have already embraced GIS, practical applications for the technology continue to multiply.

On the Lac du Flambeau Reservation, Len Fralick recently completed a map to help the tribe’s council visualize how a proposed youth center would look amid the existing buildings in the town center of the reservation. Initially, council members wanted the building to be on the small side, but now they’d like to add a few features that would require more space.

“We can use a map to help the council understand the increased space that is required for developing a larger youth center, and GIS is the tool we are using to do that,” he says. “It’s essential to our work. We basically use it every day.”

1/ For more on this, see “Maximizing the tribal land buy-back program: How priority lists can help tribes influence what’s purchased,” in the July 2014 issue of Community Dividend.

2/ Based on a review of the course catalogs of the 37 institutions. For a list of tribal colleges and universities, visit the web site of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium at www.aihec.org.

3/ For more on the office’s services, visit bia.gov/WhatWeDo/ServiceOverview/Geospatial.