Disability is a circumstance that most people believe happens to someone else. That’s why most people don’t buy individual policies to protect themselves.

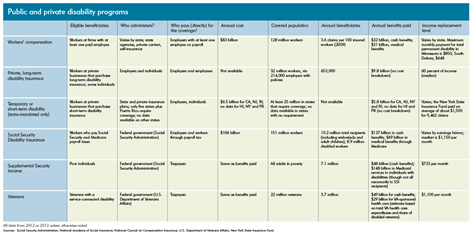

In place of individual protection, very large plans or programs have evolved over time that offer protection against the ravages of aging and accidents that can occur on the job or off. In all, these programs provide disability coverage to most workers and pay disability benefits to at least 20 million individuals annually (not including spouses and children who also qualify).

That number is artificially low because nationwide data for private disability plans are scarce. But of this total, the large majority—roughly 95 percent—of those receiving disability payments are receiving them through one of three federal government programs: Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for individuals with a disability and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

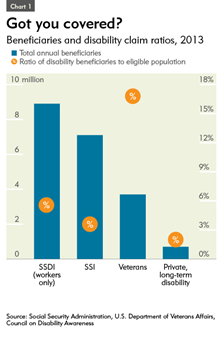

Disability coverage varies widely. SSDI covers anyone having paid into Social Security for 10 years, which is currently more than 150 million workers. SSI-disability is technically available to 195 million adults aged 18 to 64, but recipients must be extremely poor. Private, employer-based long-term disability insurance plans reportedly cover 32 million workers, according to the Council on Disability Awareness (CDA), an industry group representing long-term disability insurance companies. There are also a handful of federal disability plans for specific occupations—railroad employees, coal miners—that cover a tiny fraction of all workers.

Most programs protect against long-term disability of any sort, incurred on the job or off. But other types of protection exist. Workers’ compensation covers 128 million workers for job-only related injuries and related time away from work; roughly 40 percent of workers also have short-term disability policies, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally speaking, most coverage comes through an insurance model, where there are distinct candidate pools, upfront costs to potential beneficiaries (and/or their employers) and defined benefits for those qualifying. Others, like SSI and VA, are designed more like a social safety net; these programs provide defined benefits for qualified individuals, with no payment required.

There is some overlap among programs. For example, a person can receive SSDI and still qualify for other coverage. According to a Congressional Research Service report, about 6 percent of SSDI beneficiaries in 2012 also received benefits from either workers’ compensation or a private disability plan.

More recipients, except not

Each of these programs has experienced significant—but in some cases dissimilar—trends in recent years. Broadly speaking, the total number of recipients has jumped in the federally sponsored disability programs. Annual recipients of SSDI (workers only) and SSI rose by 52 percent and 28 percent, respectively, from 2005 to 2013. The number of people receiving veterans disability increased by 42 percent over the same period—likely due to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—while the eligible population declined by 16 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Statistics on private, long-term disability plans are less robust. Available data show that the annual number of private disability recipients has stayed mostly level since 2009, at around 660,000, according to the CDA, whose members represent 75 percent of this market. In comparison with the three federal plans, long-term private disability plans make up a small fraction of total beneficiaries and have a lower incidence rate (see Chart 1). The number of new beneficiaries is also much smaller for private plans—about 150,000 in 2013, compared with more 623,000 and 888,000 for SSI and SSDI, respectively.

The annual number of workers’ compensation claims is considerable—there are no nationwide claim data, but California (with about 10 percent of covered workers) saw almost 500,000 claims in 2011, according to an annual state report. However, in contrast to growing disability in federal programs, the national rate of workers’ comp claims (per 1,000 insured workers) was cut in half from 1995 to 2009, according to the National Council on Compensation Insurance, which did not respond to data requests.

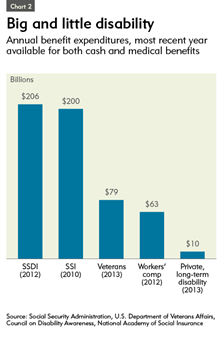

With much higher enrollments, federal disability programs dominate total program outlays. Combined, recipients of SSDI, SSI and veterans disability received almost $500 billion a year in cash and medical benefits (see Chart 2). The only private program in the same neighborhood is workers’ compensation, at $63 billion in benefits.

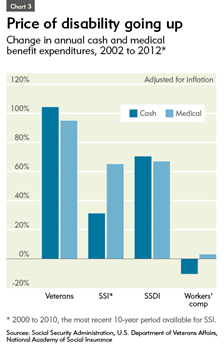

Costs for both cash and medical benefits have also been rising steadily for public disability plans, while those for workers’ compensation have stayed in check (see Chart 3). By comparison, total real costs for private, long-term disability plans (which are not listed in the chart) went up by 13 percent from 2009 to 2013, to about $10 billion, according to the CDA.

Related content

Disability and work: Challenge of incentives

More working-age adults are leaving the workforce because of disability, owing in part to demographics, the economy and changes in program eligibility

Eligibility and awards

Though overall award rates are low, persistence tends to pay off

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.