In October 2016, the Center for Indian Country Development (CICD) held its inaugural convening at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. The theme of that first conference was Early Childhood Development in Indian Country, a fitting recognition of the Bank’s considerable research in this area and of the real social benefits of investing in the youngest members of society, especially American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) youth.

Research highlighted both the social and the economic case for high-quality early childhood development (ECD) programs: “Not only do such programs reduce societal costs and increase tax revenue, but they can boost future labor force productivity, a key ingredient of economic growth.1 Minneapolis Fed economist Rob Grunewald’s presentation and research also informed participant that the return on investment of these programs demonstrates that for every dollar invested in early childhood programs, society reaps a return of up to $16.2 Early childhood education and quality child care advocates believe that this monetary return on investment also has a human capital return for the child and his or her primary caregivers, which ultimately benefits the entire community. As Grunewald says in his research, “The public benefits from reduced societal costs and increased tax revenue (are) larger than private benefits to children and their families.”3

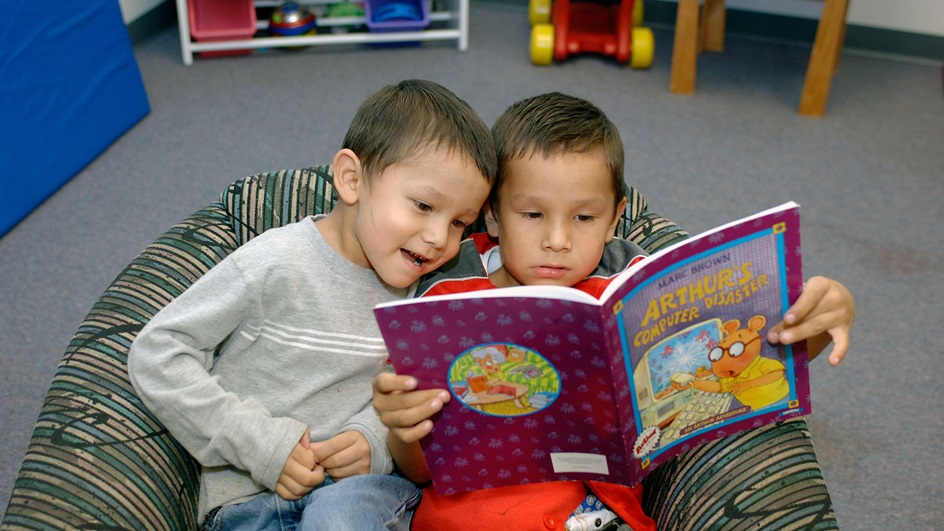

Photo: Casey Family Programs

Indeed, while “sustaining the gains children made in early childhood during elementary school and beyond is important to achieving these high returns,”4 chronic school absences are a major challenge to sustaining ECD gains for AIAN students. The National Center for the Study of Children in Poverty (NCCP) suggests that “large numbers of chronically absent students could indicate systemic problems that affect the quality of the educational experience and/or the healthy functioning of the entire community.5” In its recent study on chronic school absences, the U.S. Department of Education (DOE) found that AIAN children have the highest levels of chronic absenteeism at all (K-12) grade levels.6

Chronic school absences—that is, missing at least 15 days during a school year—is a “hidden national educational crisis,” according to the DOE. 7 Attendance Counts, a national educational advocacy organization, defines chronic absenteeism as missing 10 percent or more of school in an academic year. Starting as early as kindergarten, missing that much school is directly associated with declining academic performance. This is where it is most important to reinforce parents, families, and communities as essential educational resources.

Photo: Casey Family Programs

The model for strengthening family and building community already exists in ECD research. These programs not only nurture young children, they also encourage and promote parental growth and development. This is consistent with the Center for the Study of Social Policy finding that early childhood programs create natural support networks for parents, which reinforces the practice-based evidence of parental and community benefits. Moreover, in terms of health promotion and family strengthening, these networks enhance parental resilience, social connections, and knowledge of parenting and child development; provide concrete support in times of need; and promote social competence.8

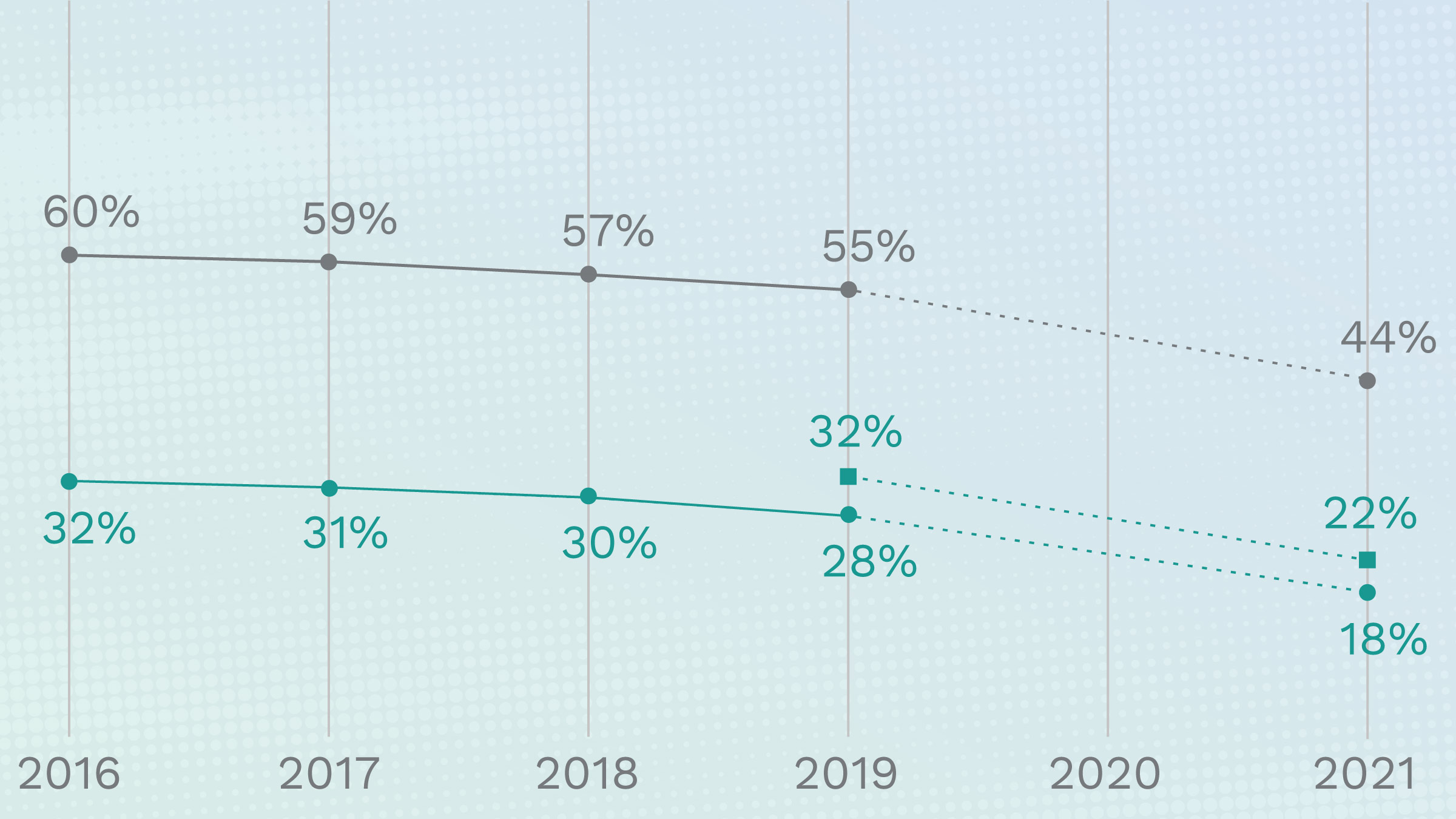

According to the DOE study, AIAN middle and high school students show the highest levels of chronic absenteeism among all races/ethnicities: 22.2 percent for middle school students and nearly 28 percent for high school students. Of high interest to ECD advocates, professionals, and tribes is that the DOE data and report also show startling disparities for AIAN K-5 students: Nearly 20 percent of these very young students are chronically absent from school compared with fewer than 10 percent of white K-5 students nationally.9

The effects of chronic absenteeism are stark. For example, if you’re an American Indian student in Minnesota, your chances of graduating from high school in four years are lower than for any other racial and ethnic group. Minnesota ranks 45th in the nation in on-time graduation rates for American Indian students—only slightly more than half of American Indian high school seniors in Minnesota graduated on time in 2015. The graduation rate for Indian students in Minneapolis is even lower at 36 percent. Despite some improvement over the past four years, the numbers remain hard to comprehend.

The documented gains that AIAN children and their families realize from ECD demonstrate its protective and resiliency power to level the playing field for vulnerable students and their families. To sustain these gains and realize the benefits advocates, educators, and others need to work both strategically and with urgency with primary care givers to ensure that these students are present in school every day and receiving everything they need to develop their fullest potential.

In future blogs for the CICD, I will explore some of the issues and solutions to chronic school absences for AIAN students. My initial focus will be on early learners and K-5 students. I will also invite readers to engage with me in a dialogue about culturally responsive local solutions (practice-based evidence) that are showing promise, evidenced-based practices that are being adopted or adapted by Tribal ECD practitioners and K-5 educators, as well as community-based collaborative approaches that address chronic absenteeism from a whole-child perspective.

Resources

https://www2.ed.gov/datastory/chronicabsenteeism.html#intro

http://www.attendanceworks.org/about/

http://www.chalkboardproject.org/sites/default/files/Oregon-Research-Brief-June-20-2012.pdf

https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pdf/studies/2006463.pdf

Endnotes

1 Grunewald, Rob. 2016. Investments in Young Children Yield High Public Returns. Cascade 93, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Fall.

2 Grunewald, Rob. 2016. Investments in Young Children Yield High Public Returns. Cascade 93, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Fall.

3 Grunewald, Rob. 2016. Investments in Young Children Yield High Public Returns. Cascade 93, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Fall.

4 Grunewald, Rob. 2016. Investments in Young Children Yield High Public Returns. Cascade 93, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Fall.

5 Chang, Hedy N., and Mariajosé Romero. 2008. Present, Engaged, Accounted For: The Critical Importance of Addressing Chronic Absences in the Early Grades. National Center for Children in Poverty. Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

6 U.S. Department of Education. 2013-14. Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) for the 2013-14 School Year.

7 U.S. Department of Education. Chronic Absenteeism in the Nation’s Schools: An Unprecedented Look at a Hidden Educational Crisis.

8 Center for the Study of Social Policy. 2003. Protective Factors Literature Review: Early Care and Education Programs and the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. Strengthening Families Through Early Care and Education, pp. 1-20.

9 U.S. Department of Education. Chronic Absenteeism in the Nation’s Schools: An Unprecedented Look at a Hidden Educational Crisis.