The most common child care environment is not a licensed child care center: it is a private home where the care provider’s work is typically unlicensed and unregulated by public agencies. A growing number of states have turned their attention to this so-called family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) segment of the child care ecosystem.

While definitions can differ, the term is generally meant to encompass care providers who work in an environment that doesn’t require a state license—likely because the number of children being cared for is too low. Examples of FFN child care range from a grandmother watching a child a few hours a week for free to a paid nanny working full-time.

There are not as much data about the FFN sector as there are about more formal providers due in large part to the unregulated nature of FFN child care work. However, some data sources do exist—and some states are starting to invest in efforts to better understand and support the FFN sector as part of their early childhood development strategy.1

National data

The federally funded National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), last administered in 2012, surveys parents about their child’s care environment. While it doesn’t incorporate specific FFN verbiage, it does contain some distinctions that provide a sense of the size and character of the market.

The NSECE differentiates among providers based on three main factors: whether child care is provided in a home or in a child care facility, whether a provider is listed in state registries of child care providers, and whether a provider is paid or not. Providers who work in a home and are unlisted are most likely to fall within the bounds of common FFN child care definitions.

The NSECE reveals several key roles that FFN can play for families with young children. For example, unlisted providers are far more likely to be available during nonstandard work hours: 67 percent of paid, unlisted providers and 82 percent of unpaid, unlisted providers are available during the evening, overnight, or on weekends, compared to just 8 percent of child care centers and 34 percent of listed in-home child care providers.2

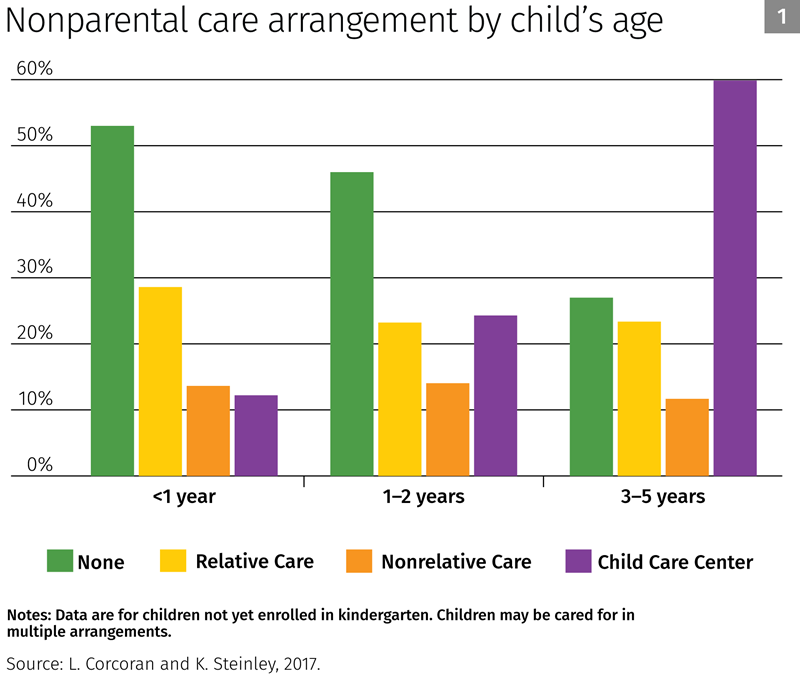

FFN child care also plays a large role in the lives of our nation’s very youngest. NSECE results show that about 28 percent of children under age one have a weekly child care arrangement with a relative, about 4 percentage points higher than for children age one to five. Meanwhile, average usage of child care centers increases from 12 percent for infants to 60 percent for preschool-age children. (See Figure 1).3

Implications for child care subsidies

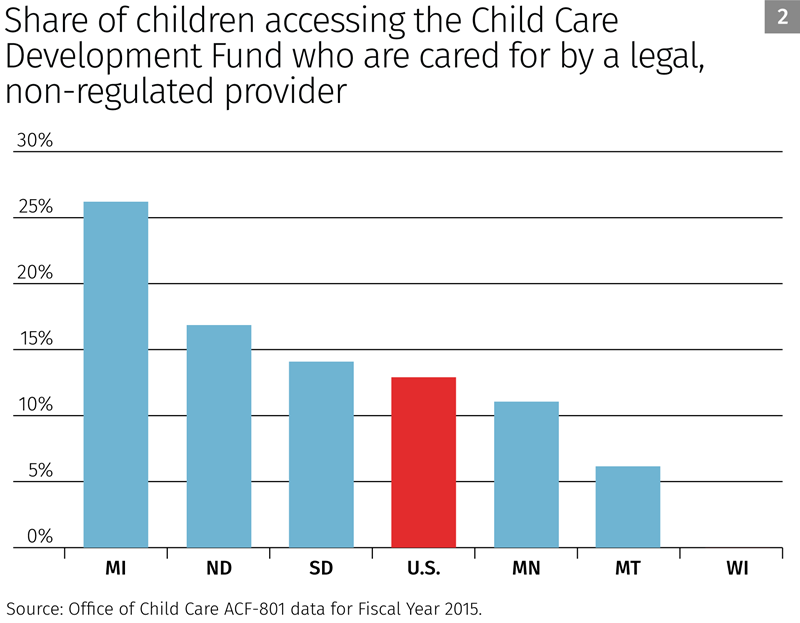

Most states allow participants in subsidies provided through the Child Care Development Fund (which encompasses the Child Care Development Block Grant, but also a few other funding sources) to choose a paid FFN care environment. About 13 percent of children whose care is funded through the CCDF are cared for in a non-regulated setting, a distinction that would capture many FFN providers. These providers often have to meet other legal requirements to qualify for subsidy payments, but remain unregulated otherwise.

Within the Ninth District, over 25 percent of children in Michigan with a child care subsidy receive care from an FFN provider, about double the national average. Meanwhile, just over 5 percent of children in Montana with a child care subsidy receive FFN care, while Wisconsin doesn’t provide child care subsidy payments to FFN providers. (See Figure 2.)

Endnotes

1 For examples, see “Supporting License Exempt Family Child Care” from the National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance; and “Improving the Quality of Family, Friend, & Neighbor Care,” a literature review prepared by the Oregon Department of Education’s Early Learning Division.

2 “Fact Sheet: Provision of Early Care and Education during Non-Standard Hours,” OPRE Report No. 2015-44, NSECE Project Team, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015. Available here.

3 L. Corcoran and K. Steinley, Early Childhood Program Participation, From the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2016, NCES 2017-101, National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2017. Retrieved on June 27, 2018, from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch. Author’s calculations.