Broadband access is now seen as an integral part of community development.1 The U.S. Census Bureau has been collecting information on households’ internet access since 2013, but the data had been insufficient to estimate high-speed, or broadband,2 internet access for lightly populated counties and many American Indian reservations. That changed with the recent release of the American Community Survey’s five-year (2013–2017) rolling average data for small areas. These new figures show that broadband access rates differ significantly among American Indian reservations but are, on average, low relative to national norms. Tribes and tribal organizations are working to reduce this impediment to economic development on reservations.

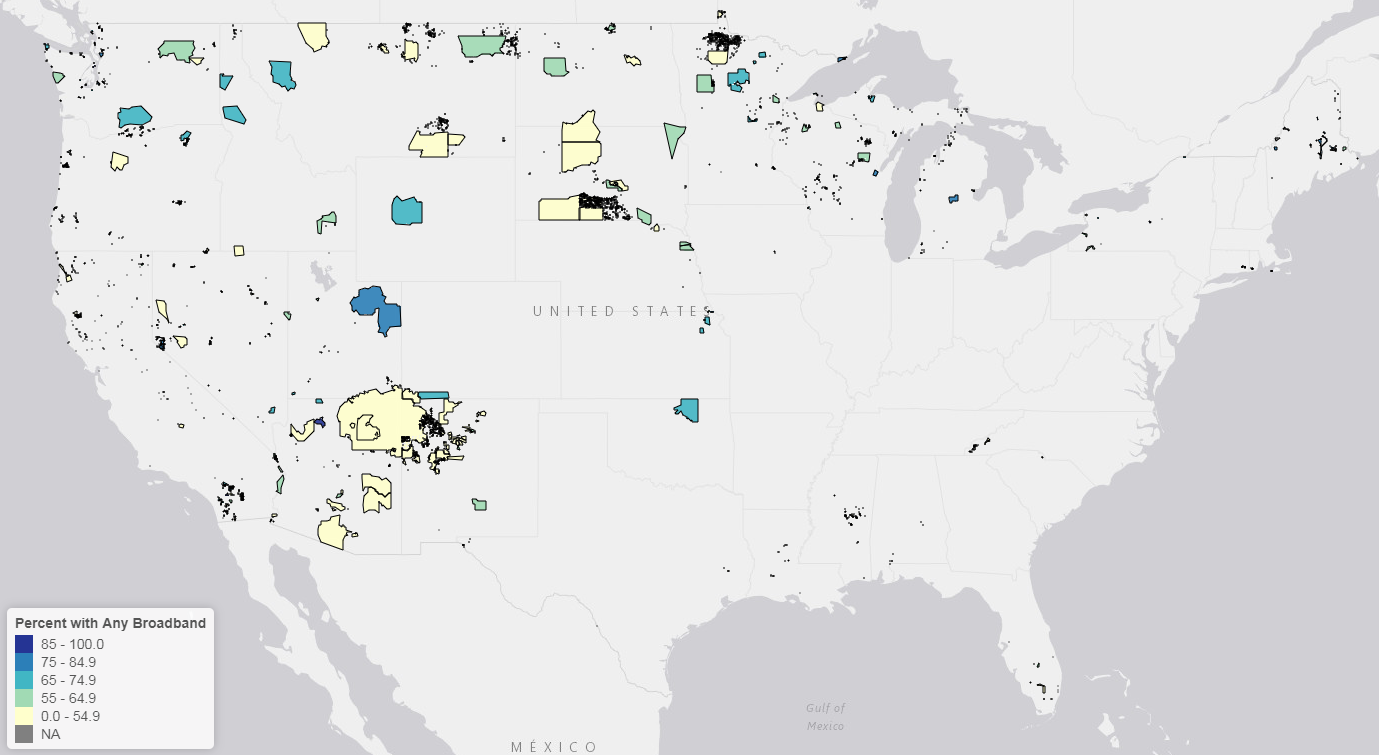

The variation in broadband access levels among reservations is illustrated in Figure 1, which maps reservations in the contiguous 48-states.3 Broadband access is categorized by the same five levels of access the Census Bureau has used for U.S counties.4 The lowest category, in light yellow, shows reservations where fewer than 55 percent of households have broadband access. This access rate is well below the national average of 78 percent as well as below the average rate in completely rural counties of 65 percent,5 and is evident in several geographically large reservations in the Southwest, Northern Plains, and Intermountain West. However, other large reservations in the same areas have rates closer to national and rural county norms. It is also evident from Figure 1 that a few reservations match or exceed the national average.

Broadband access levels for many geographically small reservations are hard to discern in Figure 1 but can be analyzed statistically. Across 262 federally recognized reservations, in the typical (median) reservation, 61 percent of households have broadband access. This percentage is significantly lower than the percentage of households with broadband access in the typical U.S county which is 69 percent. In the typical county that overlaps at least one reservation, 70 percent of households have broadband access.

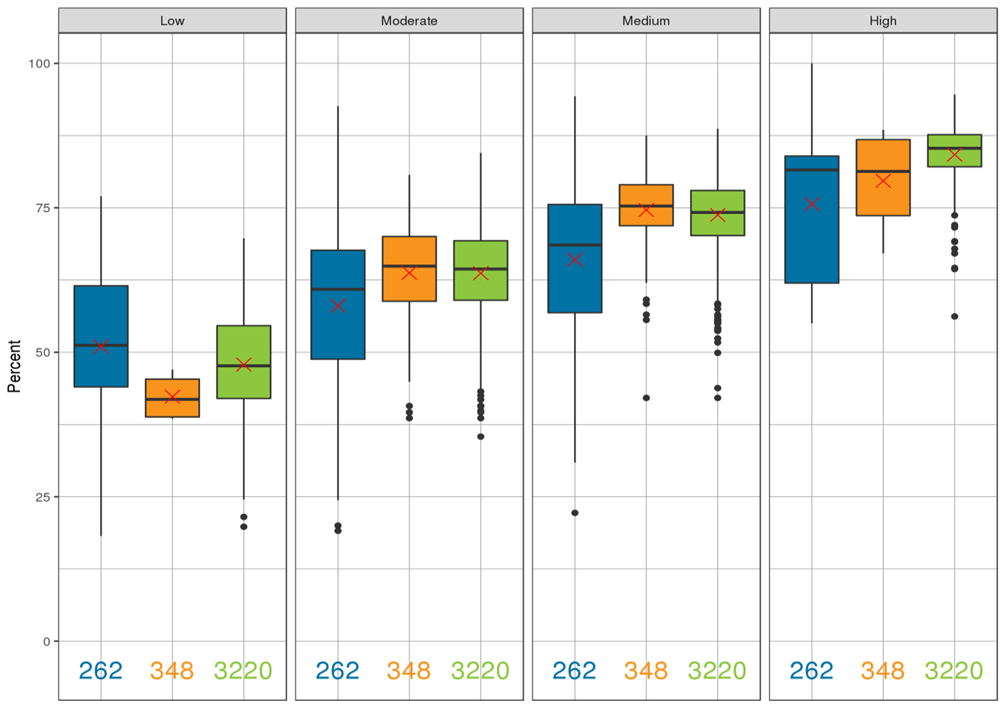

The Census Bureau has shown that counties’ rates of broadband access are positively correlated with income.6 We have found the correlation between income and broadband access for reservations is very similar as to counties. This can be seen from the box and whisker plot in Figure 2 by the similar degree of rise in the median of each box. This implies that the lower average levels of broadband access in reservations is likely attributable to lower median incomes on average, rather than a fundamentally different relationship between income and broadband access than in counties.

However, the relatively low rates of broadband access in reservation communities may also add to their economic development challenges. Enhanced Internet access may not boost all types of reservation economic activity. For example, if reservation residents increasingly purchase consumer goods online from remote suppliers, employment at local retail outlets may fall. However, the net effects of enhanced access are generally considered positive for economic vitality, including through channels such as increased productivity at local businesses, increased sales to consumers outside the reservation, improved life-style and government services that attract residents, improved medical and educational services, and more.7 For these types of reasons, tribes and tribal organizations are taking steps to enhance Indian Country’s broadband access.8

Broadband access is a potential addition to the upcoming updates to the CICD’s Reservation Profiles economic development resource.

Figure 1: Percentage of Reservation Households with Broadband Access

Note: For federally recognized American Indian reservations in the contiguous 48 states. The national county-level average percentage of households with broadband access is 78 percent. The average rate in completely rural counties is 65 percent.

Figure 2: Percentage of Households with Broadband Access, by Location and Median Household Income Level

Legend: Reservations (blue), counties overlapping reservations (orange), and all counties (green)

Endnotes

1 An argument for this case is made in work by the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank’s Community Development Department. See Jordana Barton, “Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations,” (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, July 2016).

2 In the American Community Survey (ACS), a household is considered to have broadband access if it has “at least one type of Internet subscription other than a dial-up subscription alone,” or, specifically, if the household has one or more of the following Internet subscription types: “DSL, cable, fiber optic, mobile broadband, satellite, or fixed wireless.” See Camille Ryan and Jamie M. Lewis, “Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2105,” U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey Report (September 2017). By defining access in terms of households’ subscription levels, the ACS data reflect both the raw availability of services in an area and the ability and willingness of local households to purchase one or more of the available services. For measures more limited to the physical availability of broadband services, see the Federal Communications Commission’s website Measuring Broadband America.

3 Not shown is the federally recognized Annette Island Reservation in Alaska, whose broadband access rate is 68.5 percent.

4 For data and commentary on access levels in counties, see Michael J. R. Martin, “For the First Time, Census Bureau Data Show the Impact of Geography, Income on Broadband Internet Access” (U.S. Census Bureau, December 6, 2018).

5 Camille Ryan and Jamie M. Lewis, “Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2105,” U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey Report (September 2017).

6 Michael J. R. Martin, “For the First Time, Census Bureau Data Show the Impact of Geography, Income on Broadband fInternet Access” (U.S. Census Bureau, December 6, 2018). Because this report also shows that urban location is associated with higher broadband access, we analyzed the relationship between broadband access and population density. For the relative low range of population densities relevant to reservations, we found little evidence of a significant association between density and broadband access in either reservations or counties. Accordingly, we do not discuss population density effects here.

7 For a discussion of some of these factors, see Peter L. Stenberg and Sarah A. Low, “Rural Broadband at a Glance, 2009 Edition” (U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Economic Information Bulletin 47, February 2009) and Peter L. Stenberg, “Rural Broadband at a Glance, 2013 Edition,” (U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Economic Brief Number 23, June 2013).

8 See the policy advocacy by the National Congress of American Indians or, for a local example, the initiatives of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa in Minnesota. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report discusses opportunities to improve the federal government’s support for enhanced tribal broadband access (GAO, “Tribal Internet Access: Increased Federal Coordination and Performance Measurement Needed,” GAO-16-540T, April 27, 2016).