As the pandemic took hold in northern California, Xavier Williams was abruptly laid off from his tech-sector job selling business security software—alongside 90 percent of his co-workers.

Nobody was hiring for the type of job he just lost. “I filed for unemployment, but that wasn’t coming through for four or five months” given state backlogs, Williams said. Over the next six months, he borrowed more than $20,000 from friends and family to pay rent, stay afloat, and invest in plan B: launching as a real estate agent.

“I went from having a $60K salary to having zero salary and having to depend on generating that income myself,” he said. “If I had not tried to transition to a different industry, I might still be trying to collect unemployment or back on my mom’s couch.”

Eighteen months on, Williams’ income has largely recovered. But the episode took a financial toll.

“Failing forward” not the reality for most

Elena Foshay oversees workforce development for the city of Duluth, Minn. She says that for most job seekers she works with, changing fields means making less money for a while. “That’s almost guaranteed at any level when you’re transitioning jobs,” she said. Foshay sees how a job switch—forced or voluntary—can sacrifice years of human capital: a combination of skills, knowledge, and connections that were worth a lot to an old employer, but less somewhere else.

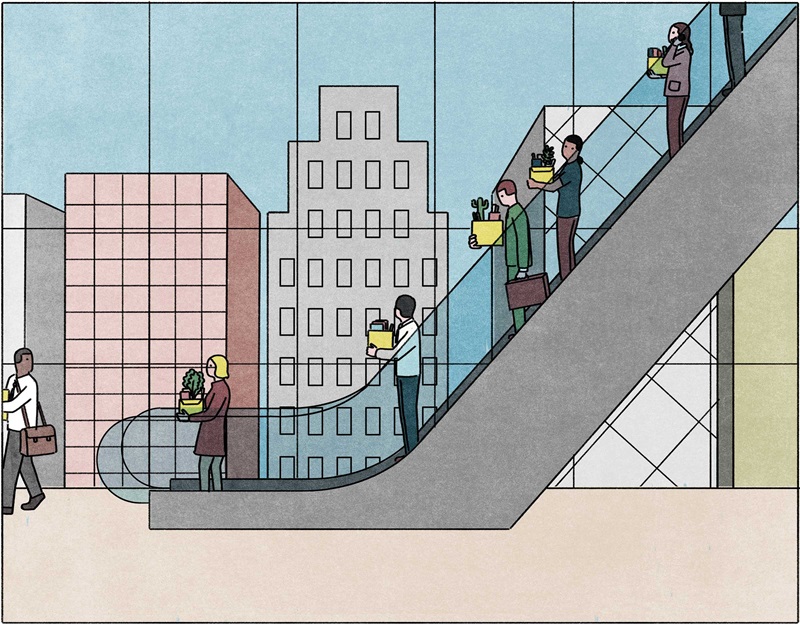

Some charmed people seem to bound up the ladder with every job switch. Certainly, there are true stories of the unexpected layoff that turns out to be a blessing in disguise. However, an unprecedented dive into 40 years of U.S. earnings data by the Minneapolis Fed validates the view from Duluth: On the whole, bouts of unemployment today last longer and strike a deeper blow to long-term income than they used to.

Earnings are becoming increasingly volatile over the course of our working lives. Notably, this increasing “income risk” is primarily a problem for college-educated people, according to a new working paper from the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute based at the Minneapolis Fed.

The likelihood of suffering a job loss hasn’t changed much over the years, said Minneapolis Fed senior economist Kyle Herkenhoff. “But when you do fall off the ladder, how far do you fall? How persistent is it? Those have really increased,” he said. “On average, you fall further. And when you get back to the labor market, some people come back with much lower wages.”

Herkenhoff and his co-authors (J. Carter Braxton, Jonathan Rothbaum, and Lawrence Schmidt1) identify these trends by applying advanced statistical techniques and heavy computing power to data on 1.2 million Americans, going back to 1982. Their unprecedented access, as part of a wider partnership with the U.S. Census Bureau, lets them link individual census survey responses to that same person’s earnings history from the Social Security Administration.2

They also use novel statistical methods to include data that seem like a no-brainer for studying income risk: stretches of unemployment. “In the past, researchers have thrown out long spells of zero earnings,” Herkenhoff said. “People who lose their job—who fall off the ladder and stay down—can’t be incorporated in existing methods. That’s where we make a methodological contribution.”

A bumpier ride, a steeper slide

An aggregate measure of income risk for U.S. workers doesn’t tell us much because it obscures multiple underlying trends.

For example, an earnings shock can last a month or two, or it can alter the path of earnings for a lifetime. The researchers find that temporary shocks have actually been decreasing slightly—our paychecks are more stable day to day. However, the size of persistent shocks has been on the rise for the employed and unemployed (Figure 1). These shocks can be positive (a big raise or promotion) or negative (a salary cut, layoff, or switching to a lower-paying job). Over time, it’s becoming a bumpier ride for American workers.

From an economist’s point of view, this volatility imposes a cost on society. It leads people to over-insure, setting aside excess savings to cushion against these future bumps. On a smoother road, they’d spend that money on other things that improve their lives or make them happy.

Not surprisingly, the earnings risk of being unemployed (top line of Figure 1) is about 40 percent larger than the risk while employed—the bumps are bigger. And losing a job today means a steeper slide backward than it used to (Figure 2). In 1985, one year of unemployment meant an average 11 percent decline in long-term earnings. By 2013, that had risen by more than half, to 17 percent.

The authors calculate huge losses to society from these trends. The findings have direct implications for how we think about retraining and unemployment insurance. The “scarring effect” of unemployment matters not just for people laid off, but for those who have to leave the workforce to care for children or elderly parents.

“Unemployment has become non-employment—long spells with large wage losses,” Herkenhoff said. “If income shocks are becoming more persistent over time, we need to be rethinking the way we insure workers.”

Which workers face greater income risk?

Probing for a source of these trends, a reasonable instinct is to consider low-skilled workers. Or perhaps it’s linked to the decline in manufacturing since the 1980s, especially in the hard-hit Rust Belt states. But the data eliminate these hypotheses.

Instead, the authors find that increasing income risk is driven by college-educated workers. Unemployed people with a college degree face over 50 percent greater earnings risk than those without. Their risk has increased over time, while the risk for other workers has hardly budged (Figure 3). The long-term, negative income consequences of unemployment are also growing faster for higher-educated workers.

There is intuition here: Higher-educated workers make more money. Their income swings will be wider, and they will have more to lose when they hit a setback. Existing unemployment insurance programs are also more effective at smoothing income for workers who make less to begin with.

This finding does not conflict with the different set of challenges imposed by rising income inequality, or with the struggles faced by people with low education and economic opportunity. Yet the lens of income risk reveals that workers with more education face increasing volatility, posing its own set of costs to society.

The role of changing technology

Last summer, a product manager named Bryce (first name only by request) was among 11 percent of staff laid off at his Colorado software company because of a merger. Although he had some time to find a new job, he worried that the highly specialized skills he had built up—training a virtual “chatbot”—wouldn’t easily translate.

“It was very niche. Not only was it a chatbot, but it was closely linked to our software,” he said. “I enjoyed it a lot. But when it came time to find a new job, that particular set of problems, those technologies that I was used to working with … I was having a hard time as I looked for new jobs, applying my experience and the things I had done to their areas.”

Thanks to a fortuitous personal connection—and living in a tech-heavy area—Bryce landed on his feet. But the data suggest his fears were reasonable. Herkenhoff and his co-authors classified the jobs of workers in their data by skill level and by the degree to which computer skills are integral to the job. Both factors were statistically significant for unemployed workers.

“We merged this stuff in, and we see that those occupations where we measure very high technology requirements were the ones that had the greatest increases in income risk,” Herkenhoff said. He offers the example of computer programmers, who risk building up expertise in languages that can become obsolete.

Back in Duluth, city workforce director Foshay sees that changing technology and practices pose a particular challenge for older workers. “We’re seeing that the workplace, and the skills needed to survive in the workplace, are changing very quickly,” she said. In a 2021 survey by Generation, a nonprofit that assists the unemployed, 53 percent of workers over 45 had been out of work for more than a year (compared with 32 percent of those under 34). Of older workers who had found a new job, 29 percent had to accept a lower salary. Fifty-two percent were unhappy and already looking for something new within three months.

For Herkenhoff, the next stage of the work involves even more data. By integrating data from the IRS, his team plans to compile the (anonymous) work history of every person who has worked or paid taxes in the United States going back to the 1970s.

“We can point to a person, in a time period, and tell you what shock that person has—was it large, small, persistent, temporary?” Herkenhoff said. “We’ll figure out who had layoffs, when, and why. And did we take care of them—or not?”

Endnotes

1 J. Carter Braxton (University of Wisconsin), Jonathan Rothbaum (U.S. Census Bureau), Lawrence Schmidt (MIT)

2 The merger is accomplished using scrambled Social Security numbers to protect data privacy.

This article is featured in the Spring 2022 issue of For All, the magazine of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Jeff Horwich is the senior economics writer for the Minneapolis Fed. He has been an economic journalist with public radio, commissioned examiner for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and director of policy and communications for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He received his master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Minnesota.