Much has been said about economic data gaps in Indian Country. The basic premise is that too often, research and data that inform policymaking and funding allocations lack specificity for Native Americans. For example, some national survey data omit Native Americans from breakdowns by racial and ethnic group due to insufficient sample sizes. Even when statistics are available, they may flatten the vibrant colors that characterize Native communities—from Alaska to Hawaii and the forests to the plains.

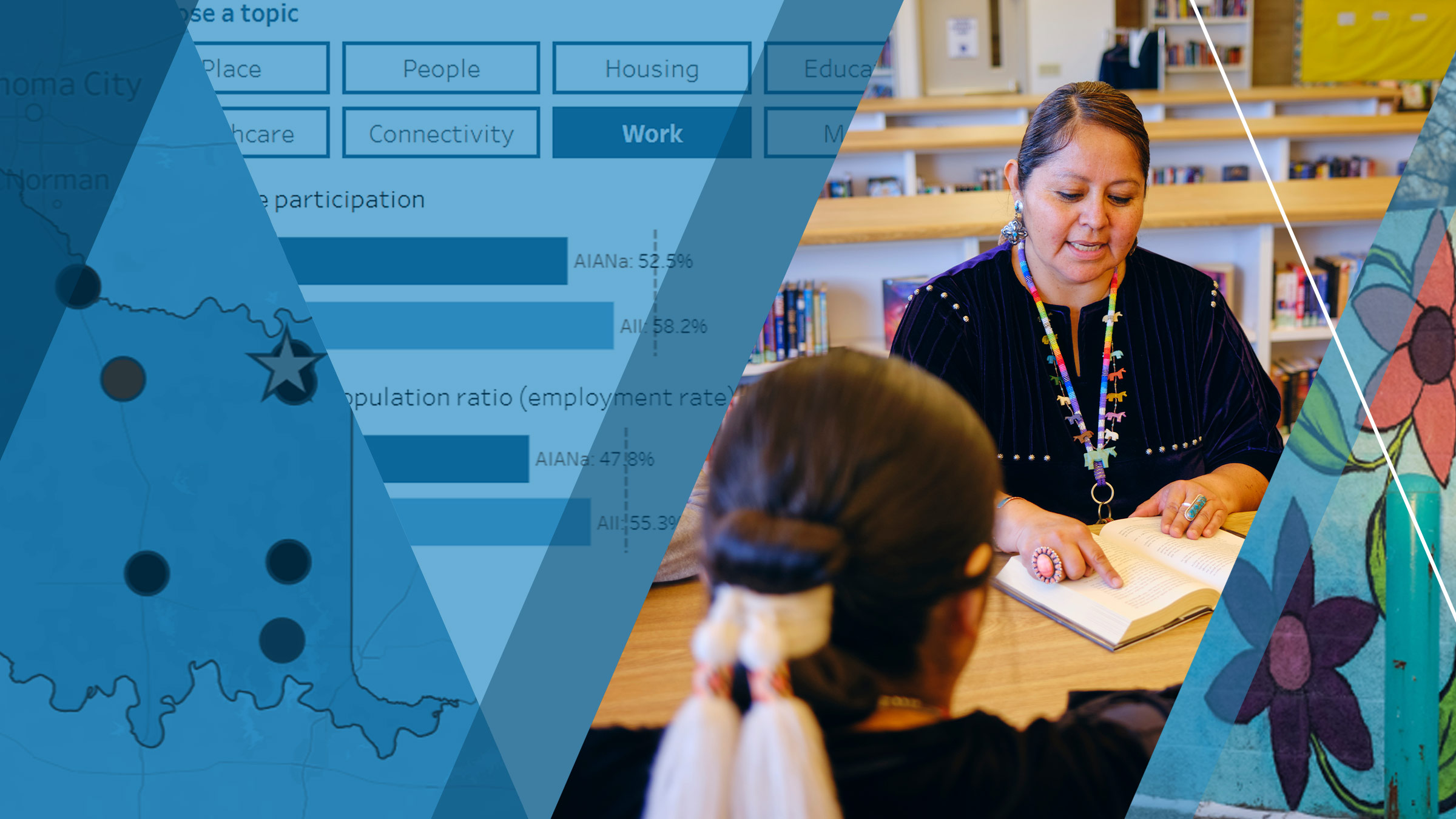

Data tools available from the Center for Indian Country Development (CICD) help tell a fuller story.

To illustrate how stakeholders can use CICD data tools to tell their own community data stories, we asked three CICD Leadership Council members to share one of the many stories that could be told from their home communities. The stories they shared are as distinctive as their communities in Connecticut, Minnesota, and Hawaii. In each case, we use CICD resources to complement their lived experience with data.

Data featured in this article come from CICD’s Native Community Data Profiles (NCDP),1 Native American Funding and Finance Atlas (Atlas), and Tribal Economic Zones (TEZ) tools—three in our suite of data resources. Throughout this article, source tools for individual data points are indicated by the tools’ abbreviations. Data points reflect the most recent data available in these tools at the time of publication.

Mashantucket Pequot Reservation (Connecticut): Bringing generosity to economic success

In southeastern Connecticut, where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Long Island Sound, the Mashantucket Pequots have lived, endured, and thrived for more than 10,000 years. CICD Leadership Council member Jean Swift (Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation), the tribe’s chief financial officer, has lived most her life in the area. In Algonquin, Mashantucket means “much-wooded lands,” Swift said. “You’re surrounded by the beauty of trees, and it doesn’t matter what time of year it is—they have beauty even in the winter.” Likewise, “Pequot means ‘people of the shallow water.’ We’re also coastal—not very far from seafood and the ocean,” she said.

Today, a small community calls the two and a half square miles of Mashantucket Pequot Reservation and off-reservation trust land home. An estimated 77 percent of residents self-identify as American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN).NCDP They reflect a community whose numbers dropped dramatically following European settlement but who, over time, worked to reclaim lost land and pursue economic opportunity. The tribe operates several enterprises, ranging from health care to entertainment to real estate.

By several economic measures, the community is prospering. Among AIAN households in the area, the estimated median household income is $81,563, which exceeds the $75,149 median household income of the United States as a whole. It’s estimated that all AIAN-headed households in the area live in single-family housing, and few reservation residents struggle to afford their housing—only 11 percent of all households in the area are cost-burdened, meaning they pay 30 percent or more of their household income on housing, compared to 31 percent in the United States as a whole. That said, Swift observes that “most homes have multiple occupants.” The share of households in the area that are considered crowded based on the U.S. Census Bureau definition of having more than one occupant per room is approximately 7 percent, compared to 3 percent of households across the United States as a whole.NCDP

Visitors travel from well outside the Mashantucket Pequots’ lands to experience the reservation’s attractions, which include a resort and casino, spa, museum, and picturesque golf course. As shown in the image below, visitors travel an average of 49 miles from their homes to places of interest on the reservation.2 Most often, they come for lodging and food, which attract 42 percent of visitors, and wholesale and retail trade, which attract 34 percent.TEZ The tribe also describes itself as one of the state’s primary employers and taxpayers.

But economic data alone don’t tell the full story. “We’re just a microcosm of the larger society. We still have our social issues,” Swift said. “I don’t know a community that doesn’t have some issues with drug abuse and addiction. We do our best to address those issues with the resources we have and to support people, whatever issues they’re facing.”

Swift also described challenges associated with taxpayer dollars flowing out of the tribal community. “One of the challenges we have is dual taxation. We see the state and local municipalities taxing our non-Native tenants from a property tax perspective. The extraction of those tax dollars hinders on-reservation economic development.”

The tribe meets challenges with what Swift described as a longstanding spirit of generosity. Even before the economic benefits of tribal gaming materialized, “there’s always been a willingness to help one’s neighbor,” she said. For example, the tribe donates to Indian Country organizations and area nonprofits, and shares swimming facilities with local schools. “Generosity is something that Pequots don’t necessarily realize we’re doing. It’s just embedded in who we are.”

As the community looks to the future, Swift sees this and other cultural values and traditions holding strong—even as younger members move away from the reservation and settle in other parts of the country. “I see this change, because it’s a little more widespread than when I was younger.” She remains optimistic that even those who move away—as she did to the Chicago area for several years—will “remember their roots and represent Pequot wherever they are.” Her grandchildren receive Pequot language instruction at the tribe’s child development center, and overall, engagement in powwows and traditional dances remains steadfast. “That’s something that’s staying the same—the respect for our culture and our traditions,” she said.

With an estimated average life expectancy on the reservation of 81 years—higher than the average life expectancy of 78 years for the United States as a whole—and an estimated zero percent unemployment rate for AIAN residents, suggesting that those who want to work can find jobs, there’s good reason to believe that those who move away may eventually return home.NCDP “They’ll bring back new knowledge, new insights, new ways of doing things, and that’s a good thing,” Swift said.

Leech Lake Reservation (Minnesota): Bringing cultural wisdom to bear on modern economic challenges

Hundreds of years ago, Ojibwe people, also known as Anishinaabe or Chippewa, traveled through the Great Lakes to settle around the lakes and densely forested areas of northern Minnesota.

“As Anishinaabe people, the prophecy we follow is to go west to where the food grows on water—which is manoomin (wild rice),” said CICD Leadership Council member Leonard “Lenny” Fineday (Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe). “The abundance of natural resources is very important to us in maintaining our way of life as Anishinaabe. That includes manoomin harvesting, fishing, hunting, gathering—those treaty-protected rights that we continue to engage in on a regular basis.”

Fineday serves as secretary/treasurer for his tribe, the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe. Located near the headwaters of the Mississippi River, the Leech Lake Reservation features some of the largest lakes in Minnesota and shares geography with the Chippewa National Forest.3 The area includes 973 square miles of land and 337 square miles of water.

Approximately 11,200 people call the Leech Lake Reservation and off-reservation trust land home, and 41 percent self-identify as AIAN.NCDP Residents blend modern and traditional ways of life. The top three industries employing people who live in the area are health care and social assistance, with an estimated 17 percent of workers; retail trade, with 14 percent; and accommodation and food services, with 10 percent.NCDP At the same time, traditional practices continue to thrive. “We have a very strong population of tribal members who still go out and practice the traditional harvesting that we’ve been doing for hundreds of years,” Fineday said.

Despite retail, lodging, food, and other attractions that prompt visitors to travel an average of nearly 50 miles to places of interest on the Leech Lake Reservation, many AIAN residents experience economic challenges.TEZ AIAN individuals in the area have an estimated per-person income of $16,530—less than half of the $41,261 per-person income in the United States as a whole. More than a third of the AIAN population, around 35 percent, experience poverty, compared to 13 percent in the United States as a whole. The estimated unemployment rate among AIAN people in the area—20 percent—is four times the approximately 5 percent unemployment rate of the United States as a whole.NCDP

Portions of the area are eligible for federal economic development programs such as New Markets Tax Credits, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Community Development Block Grants, and the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund. As shown in the image below, the community also has several affordable housing projects supported by the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC).Atlas

Although reservations are distinctive across the United States, Fineday observes many experiencing challenges similar to those of Leech Lake. “Unfortunately, I think a lot of the root cause of our challenges is related to historical trauma,” he said. “Our history has shown us that we have to be resilient.”

For those struggling with economic and social issues such as homelessness or addiction, Fineday said the tribe “takes what we believe is a proactive approach in a strategic plan that focuses on a continuum of care.” That includes hiring community recovery navigators who provide resources and service referrals.

To Fineday, his community’s resilience rests in the cultural values and traditions that shape the tribe’s approach to modern challenges. “I see our cultural identity, who we are as Anishinaabe people, our core values, and our Seven Grandfather Teachings remaining strong and being the backbone of our resilience as Anishinaabe people. Those will guide us as we continue to walk into the complexities of the twenty-first century and beyond.”

Papakolea Hawaiian Home Land: Connecting across geographic dispersion

Growing up, CICD Leadership Council member Shannon Edie (Native Hawaiian) split her time between the islands of Oahu, where she attended school, and Kauai, where she spent summers. Today, Edie—who is the executive director of the Native Hawaiian Organizations Association—lives near the Papakolea Hawaiian Home Land on Oahu, but identifies more as Native Hawaiian than with any specific local geography.

“We are unique. The majority of Native Hawaiians do not live on Hawaiian homestead land,” she said. “In order to qualify to live on Native Hawaiian Home Lands, you actually have to have a blood quantum of at least 50 percent Hawaiian, and the number of individuals who meet the requirement is relatively small compared to the overall Native Hawaiian population.”

Hawaiian homestead land is held in trust by the State of Hawaii’s Department of Hawaiian Home Lands. Beneficiaries may receive 99-year homestead leases at $1 per year. “If you qualify, you put your name on a wait list, and many people die during the time they’re on the list,” Edie said. “In order for a qualified family member to succeed to the lease, they have to have a blood quantum of at least 25 percent Hawaiian.4 The percentage of Native Hawaiians who live on Hawaiian Home Lands is relatively small in relation to the Native Hawaiian population.”

As a result, Native Hawaiians are geographically dispersed. “On Oahu and neighboring islands, Native Hawaiians are so spread out,” Edie said, adding that many have also moved outside of Hawaii due to economic necessity. “Because of our geographic isolation, groceries and other things cost so much more here than in most places in the continental United States. Salaries do not come anywhere close to meeting the cost of living here.”

But as with other communities across Indian Country, individual Native Hawaiian communities are unique. As seen in the image below, on the 0.2 square miles of Papakolea—which an estimated 1,284 individuals call home—median household income for those who identify as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NHOPI) is estimated at $100,625, which actually exceeds the $75,149 national median for all households. But while household incomes appear high relative to the United States as a whole, the estimated $32,839 per-person income for NHOPI individuals in Papakolea is lower than the $41,261 per-person income in the country overall.NCDP

Still, these data don’t tell the full story. Many Native Hawaiians and other Hawaii residents hold a few jobs, Edie said, and high housing prices “force a lot of families to move to other parts of the country in order to own a home.”

A closer look at Papakolea’s housing data shows that although relatively few households are estimated to be cost-burdened, at 18 percent compared to 31 percent nationally, a relatively high proportion are crowded, at 9 percent compared to 3 percent nationally.NCDP

Despite geographic isolation and population dispersion, Edie sees cultural traditions continuing to thrive wherever Native Hawaiians live. “Even though we are dispersed, one of the unique values we share is the concept of connection, or pilinia. It’s an umbilical cord that ties us to our family, our community, and aloha ʻāina (love of the land and natural resources),” she said. “In our community, it’s almost like we’re all family. When you meet someone for the first time, it’s as if you’ve known them forever. People might call it the ‘aloha spirit.’ We have aloha for our people, we have aloha for our families, and we have a deep respect for our land, our oceans, and our natural resources.”

When wildfires struck Maui in 2023, pilinia was evident, Edie said. “What happened on Maui brought us together as a Native Hawaiian community. We’re in a location where we’re very isolated, so when a natural disaster hits us, it can be devastating. But what happened on Maui showed the resilience of our people—our community coming together to help even those you don’t know, but you know you’re helping other Native Hawaiians.”

Part of this sense of connection stems from shared historical trauma, Edie said. “After the overthrow of our monarchy, our culture was on the brink of extinction. Native Hawaiians were not allowed to speak in our native tongue or to engage in cultural practices such as hula. At some point there began a revival of our culture, and that continues today. I think that Native Hawaiians—wherever they are—have tremendous pride in being Hawaiian. You see Hawaiians across the continent engaging in cultural practices such as hula dancing, music, and speaking the language.”

Edie remains confident that despite the economic challenges of geographic isolation, this cultural pride and renaissance will stay strong.

Telling distinctive data stories

Data stories that can be told across Indian Country are as distinctive as the Mashantucket Pequot, Leech Lake, and Papakolea communities. Even within any given Native community, many stories could be told. “Data don’t tell the full story,” as Swift observed, but data can help communicate and increase understanding of lived experiences.

Data tools available from CICD support stakeholders in telling stories that amplify a variety of experiences across Indian Country. With this enhanced understanding, decision-makers can better address Native communities’ economic needs.

Endnotes

1 The NCDP data tool aggregates publicly available data from a variety of sources. Depending on the data point and underlying data source, measures may reflect individuals identifying as American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) alone, individuals identifying as AIAN alone or in combination with another race, or all individuals or households in the geography of interest. Some data points—such as those derived from the American Community Survey—reflect estimates rather than actual measured quantities and are noted here accordingly as estimates. For data details, visit the community profile in the data tool. For additional details, see the tool’s About the Data resource.

2 Due to differences in underlying data sources, Mashantucket Pequot Reservation geographies of focus vary somewhat across CICD data tools. Data presented from the TEZ tool reflect the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation. Data from the NCDP tool reflect the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation and off-reservation trust land.

3 Due to differences in underlying data sources, Leech Lake Reservation geographies of focus vary somewhat across CICD data tools. Data presented from the Atlas and TEZ tool reflect the Leech Lake Reservation. Data from the NCDP tool reflect the Leech Lake Reservation and off-reservation trust land.

4 According to the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, when an initial leaseholder—who must have a blood quantum of 50 percent—designates a successor to the lease, the blood quantum requirement depends on the successor’s relationship to the original leaseholder. If the successor is a spouse, child, grandchild, or sibling, then the successor must have a blood quantum of 25 percent. If the successor is a parent, widow or widower of the successor’s children, widow or widower of the successor’s siblings, or a niece or nephew, then the blood quantum requirement is 50 percent.