On the Flathead Indian Reservation in western Montana, against a timeless backdrop of jagged mountain peaks and rolling plains, modern enterprises dot the landscape. From time immemorial, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) have lived, endured, and thrived in this area by honoring tradition as they embrace new opportunities.

This ability to weave past and present can be seen in the tribe’s approach to economic development. In deliberate, culturally centered ways, CSKT has grown and diversified a family of tribal enterprises that support the community’s traditions and long-term economic prosperity. For insight into this approach, the Center for Indian Country Development (CICD) conducted interviews with nine past and present tribal enterprise executives, enterprise board members, and economic development leaders, who identified five key factors in CSKT’s enterprise development. Their perspectives, summarized in this article, offer lessons in building business ventures that honor the past, present, and future.

The impetus to pursue enterprise building

First, some historical context on what drove CSKT to pursue tribal enterprise development. Like many tribal communities, CSKT has historically experienced taxation constraints, limited access to financial services and capital, and division and allotment of its land as the demand for territory and resources overrode treaty terms. In 1904, the Flathead Allotment Act opened the reservation to settlement by non-tribal members,* which resulted in a loss of grazing land that interviewees described as having a devastating impact on tribal members’ cattle, horse, and bison operations. After the timber industry took hold in the early 1900s, tribal finances relied heavily on timber as a revenue stream. Over time, tribal leaders needed to find new ways to generate revenue and create job opportunities—and preserve CSKT’s natural resources for future generations.

In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) provided a legal framework for tribes to adopt a constitution and form businesses. Under Section 17 of the act, tribes may establish corporations that are owned by the tribal government and are not subject to federal income taxes. Following the passage of the IRA, CSKT adopted a constitution that laid the foundation for the tribe’s entry into business operations.

The first factor in successful tribal enterprise development that our CSKT interviewees identified is built directly on that foundation.

Key factor 1: The governance model supports enterprises

CSKT’s constitution grants the tribe the power and duty to charter organizations for economic purposes. It further outlines CSKT’s power to elect managing boards of tribal enterprises and accept grants and donations. Importantly, the tribal council operates as the primary shareholder of its tribally owned enterprises but does not manage their day-to-day operations.

In this way, the constitution provides for separation of powers between the tribal government and enterprise operations. At the same time, the tribal council’s nomination of enterprise board members ensures that enterprises keep the tribal government’s interests in mind. Board appointees represent tribal council interests, but the boards and their management teams operate their businesses at a distance from political decision-makers.

“The tribe has been supportive but not directive,” said one enterprise leader. “The nice thing about the tribal council is that they’ve left business leaders to direct their own company. The tribal council has allowed them to choose how they invest their money and to continue to develop the company the best way they see fit.”

This separation of powers also helps the tribal council objectively focus on community interests. A tribal official explained: “When the political body changes, it doesn’t exercise any more direct influence on the operations of the corporations than the prior council. Instead, the tribal council in its capacity as primary shareholder selects new board of directors members as director terms expire and provides general guidance and some strategic direction.”

Key factor 2: Credit solutions lay groundwork for growth and expansion

Interviewees also identified addressing credit challenges as a key factor in CSKT’s successful enterprise development. Lack of access to capital and credit has historically constrained tribal communities’ economic development and ability to invest in business and infrastructure. Over time, CSKT identified creative ways to enhance the availability of capital to support new enterprises.

An early example: In 1936 the tribe established the Tribal Credit Program to make loans that would enhance tribal members’ economic and social well-being. Since its inception, the program has helped tribal members purchase homes, pursue education, and grow enterprises. In the words of one tribal official, “Tribal Credit was the root of all successes.”

Over time, the tribe also grew capital for enterprise investments by leveraging one-time government settlements. Like many tribes, CSKT has received sizeable settlement disbursements from the federal government. As described by one tribal official, “CSKT has been strategic about the large windfalls of funding that have come into the government. When CSKT receives funding, they look at the short- and long-term benefit.”

Long-term strategies have included moving a portion of settlement funds into an investment pool and building a trust fund dedicated to tribal enterprise investments. Such investment vehicles have allowed CSKT to earn investment income while addressing more immediate government-service needs.

Another important way the tribe brought capital resources into the community was by establishing a tribally owned bank. The council wanted a financial institution that understood CSKT’s governing systems, in addition to its capital needs, and was invested in the community. Native American Financial Institutions (NAFIs)—including banks, credit unions, and loan funds—are characterized by public commitments to provide affordable and culturally informed financial services, credit, and capital in Indian Country. (For locations, asset sizes, and other details about NAFIs, see CICD’s Mapping Native American Financial Institutions tool.) In 2006, the tribe opened Eagle Bank.

Although the bank initially struggled with modest assets and competition from other banks in the region, the tribe deployed a variety of strategies to support its success. One bank leader observed: “The tribe keeps their money at Eagle Bank, which is smart because they’re supporting their own bank.” The tribal council also encouraged tribal enterprises to bank there. At the same time, bank officials spread the word that “the bank is not only for tribal members,” according to a bank leader.

The bank further diversified its portfolio through market investments, loans purchased from other banks, and its own lending decisions. In the words of a bank leader, “The only way to be a high-performing bank in this area is to appeal to everyone’s needs.” Eagle Bank also forged partnerships with other Montana banks to offer more substantial loans and compete with bigger banks in the region. Today, Eagle Bank boasts approximately 8,000 members and, as of June 2023, approximately $126 million in assets.

Key factor 3: Sequenced development builds resilience

In the years since CSKT expanded beyond the timber industry, the tribal council has approached new enterprise opportunities carefully. Interviewees described the importance of sequencing development to ensure long-term success. As one tribal official put it, “When CSKT establishes enterprises, they look into how to use the current opportunity to benefit future generations.”

Case in point: CSKT’s 2015 purchase of the Se̓liš Ksanka Ql̓ispe̓ Dam, which controls the flow of water from Flathead Lake into the Flathead River, followed decades of saving and planning. According to interviewees, tribal leaders saw value in diversifying into the energy industry and viewed the purchase as an opportunity to regain sovereignty over parts of the lake and river. The tribe saved for 30 years to acquire the capital needed for the purchase without draining tribal treasuries. Fifteen years ahead of the purchase, the tribe created a government department dedicated to building the leadership, skilled workforce, and systems needed to successfully operate the dam. After assuming ownership, this foundation helped CSKT weather early challenges with energy pricing and operations.

In considering new enterprise opportunities, the tribal council also weighs how the new opportunity would fit with the overall mix of enterprises. This perspective has translated into investing finite tribal dollars into markets that can provide employment opportunities and dividends back to the tribal council—in a way that doesn’t compete with existing tribal member-owned businesses. “The goal of tribal enterprises is not to compete with other tribal businesses,” said one enterprise leader.

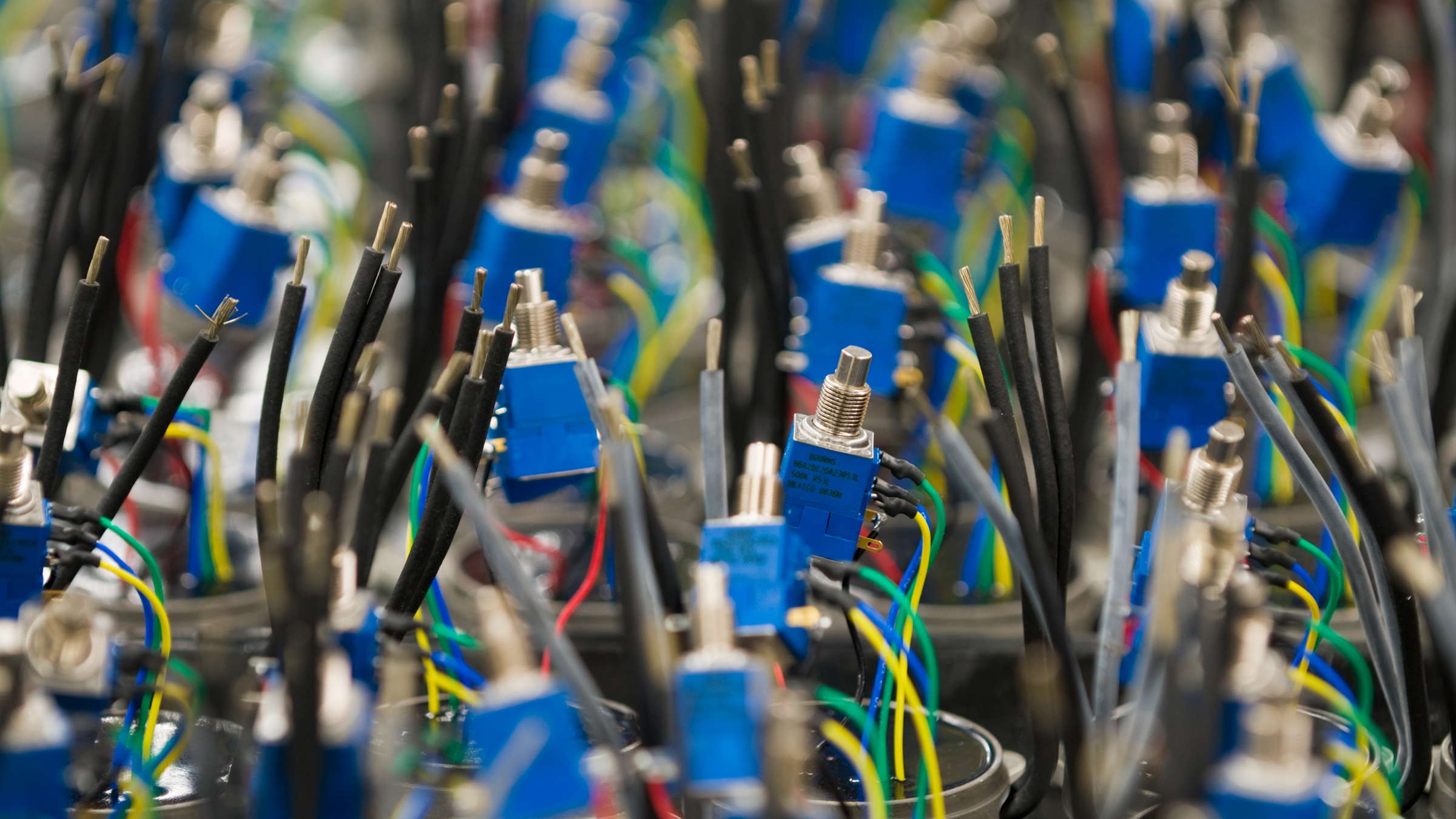

With these principles in mind, CSKT ventured into federal contracting. In the early 1980s, the tribal council identified an opportunity to operate a manufacturing facility that could build military defense instruments for the federal government. “The tribe wanted to expand beyond the timber and agriculture industries and step into a new sector,” an enterprise leader said. In 1984, the tribal council established S&K Electronics.

Initial tribal council investments gave the enterprise “some legs to get up and walk,” the enterprise leader said. Several years into operation, the company received another boost through 8(a) certification. Designed for socially and economically disadvantaged small businesses, the U.S. Small Business Administration’s 8(a) Business Development program provides training, technical assistance, and federal contracting preferences. “That program was really a key to building a groundwork for success,” the enterprise leader said.

A tribal official described S&K Electronics as “the first successful and autonomous” CSKT tribal enterprise that followed several unsuccessful endeavors in the 1950s and 1960s. S&K Electronics also marked the first of a family of enterprises that would, over time, help tribal leadership refine their relationships with enterprise boards.

Key factor 4: Industry diversification creates complementary revenue streams

In the early 1990s, CSKT turned to gaming as another potential source of revenue and jobs. Following the passage of the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, CSKT conducted a market analysis to determine the optimal location for a gaming establishment. Findings pointed to the tourism-rich community of Polson on the shores of Flathead Lake, and a few years later CSKT opened the KwaTaqNuk Resort and Casino there. The gaming operation not only leveraged existing summer tourism but also helped further develop the area’s tourism industry and created seasonal and permanent employment opportunities. The facility also provided a meeting ground for community and cultural events. In time, the tribe opened additional gaming operations and in 2006 founded S&K Gaming, LLC to oversee them.

Meanwhile, as S&K Electronics grew, tribal leaders explored opportunities to diversify CSKT’s federal contracting portfolio. In 1997, the tribal council incorporated S&K Technologies as a division of S&K Electronics focused on providing engineering, information technology, and other services complementary to S&K Electronics products. Benefiting from the company’s prior experience, S&K Technologies acquired 8(a) certification and quickly began earning federal contracts. In 1999, S&K Technologies spun off into a company in its own right.

Interviewees described the introduction and spinoff of S&K Technologies as a key step in CSKT’s enterprise diversification. By separating these companies into different sectors of the defense market—products and services—the tribal council helped distinct enterprises win customers they could support in complementary ways. In time, S&K Technologies further diversified its federal contracting portfolio by establishing a family of limited liability corporations it oversees as a holding company.

None of this diversification has been taken lightly. As one enterprise leader put it, “As you’re diversifying, you’re going into a riskier environment. What we have to do is take small steps into those environments so we don’t take on a full-blown risk as we diversify.” Diversification is baked into the company’s structure: “We have full-time people who have the part-time job of looking where to diversify.”

Key factor 5: Community reinvestment supports public services and cultural preservation

As tribally owned enterprises, CSKT’s suite of businesses provide key revenue streams for supporting the tribal government and, by extension, public services. According to interviewees, the tribal council directs enterprise dividends toward a variety of community services and activities, including education, teacher training, elder services, land purchases, language revitalization, powwows, and cultural committees. “Tribes have a unique focus on education and culture to ensure the subsistence of Indian culture and meet community needs that the federal government does not provide for,” said one tribal official.

This focus on community well-being connects tradition to present and future needs. As articulated in the tribe’s description of its family of enterprises, “Taking responsibility for ourselves in order to ensure our future has always been our way of life.”

A model to learn from

Today, CSKT serves as the primary shareholder of 18 tribally owned enterprises that span diverse industries. Almost all CSKT enterprises were established as Section 17 corporations under the IRA. Collectively, these enterprises employ approximately 1,200 workers and help fund vital community services. While the tribe continues to experience labor shortages and other challenges, its enterprise successes—built on supportive governance, credit solutions, sequenced development, industry diversification, and community reinvestment—offer valuable insights for other tribes. One by one, individual tribes’ unique enterprise stories can collectively broaden our understanding of what economic development looks like across Indian Country.

Endnote

* The Flathead Allotment Act followed passage of the General Allotment Act, also known as the “Dawes Act,” in 1887, which opened treaty-protected lands for non-Native settlement.