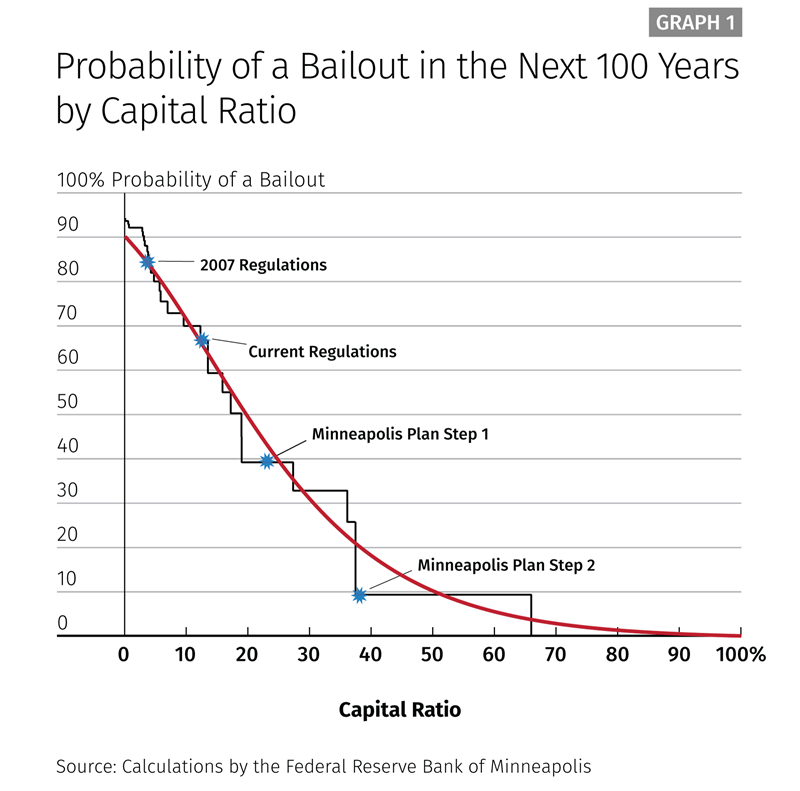

The Minneapolis Plan reduces the risk of a financial crisis, and resultant bailout, over the next 100 years to 9 percent, with the net benefits equaling 15 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), as shown in Table 1. The current regulations, put into place after the 2008 financial crisis, are considerably less effective in reducing risk, lowering the 100-year chance of a bailout from 84 percent to 67 percent.

Summary of the Minneapolis Plan

- What is the TBTF problem the Minneapolis Plan is designed to solve?

Banks are TBTF when their failure or potential insolvency can cause widespread damage or “spillovers” to other banks, financial markets, and the broader economy. When facing such a devastating outcome for their citizens, governments are usually forced to step in with taxpayer bailouts to stabilize the TBTF firms. Such bailouts are not made to support the banks themselves, but to prevent the fallout on Main Street. In most other sectors of the economy, firms are able to fail without requiring taxpayer bailouts or triggering widespread economic damage. The goal of the Minneapolis Plan is a financial system that enables the U.S. economy to flourish without exposing it to large risks of financial crises or without requiring taxpayer bailouts.

- What will the Minneapolis Plan accomplish?

The Minneapolis Plan is designed to reduce the risk of a financial crisis and bailout to as low as 9 percent while passing a benefit and cost test. We estimate that the current regulations put into place after the 2008 financial crisis reduced the 100-year chance of a bailout from 84 percent to 67 percent. The Minneapolis Plan reduces that risk to 9 percent and provides an overall net benefit to the economy. There is a trade-off involved in ensuring greater safety in the U.S. economy; we show that the added safety here is well worth the cost.

- What are the keys to ending TBTF?

Ending TBTF means either substantially reducing the chances of failures (and hence bailouts) of TBTF firms or restructuring the financial system such that banks are no longer so large, important, or interconnected that their failures cause widespread harm to the economy. Policymakers could make banks less likely to fail by requiring that they issue more equity to absorb losses. Governments could also reduce the damage caused by failures by forcing banks to reorganize themselves such that their failures will be unlikely to spread to other firms. We do not think a mandate prohibiting bailouts is credible, because tying policymakers’ hands without addressing the underlying risks from TBTF firms could inflict widespread damage on the U.S. economy. The risks posed by large banks must be addressed before bailouts can be prevented.

- What is the Minneapolis Plan?

The Minneapolis Plan to end TBTF has four steps:

- Step 1. Dramatically increase common equity capital, substantially reducing the chance of a bailout

The Plan requires the largest banks to issue common equity equal to 23.5 percent of risk-weighted assets, with a corresponding leverage ratio of 15 percent. This level of capital maximizes the net benefits to society from higher capital levels. This first step substantially reduces the chance of a public bailout relative to current regulations from 67 percent to 39 percent. This substantial improvement in safety comes with net benefits.

- Step 2. Call on the U.S. Treasury Secretary to certify that individual large banks are no longer systemically important or else subject those banks to extraordinary increases in capital requirements, leading many to fundamentally restructure themselves

Once the new 23.5 percent capital standard has been implemented, the Plan calls on the U.S. Treasury Secretary to certify that individual large banks are no longer systemically important. The Plan gives the Treasury Secretary discretion in making this determination so that the Secretary can rely on the best information and analysis available. If the Treasury Secretary refuses to certify a large bank as no longer systemically important, that bank will automatically face increasing common equity capital requirements, an additional 5 percent of risk-weighted assets per year. The bank’s capital requirements will continue increasing either until the Treasury Secretary certifies it as no longer systemically important or until the bank’s capital reaches 38 percent, the level of capital that reduces the 100-year chance of a bailout to 9 percent.

Step 2 is a critical step for ending TBTF. Under the current regulatory structure, there is no explicit timeline for ending TBTF and regulators never have to formally certify that they have addressed systemic risk. Instead, banks and designated nonbank financial firms under the current regime can continue to operate under their explicit or implicit status as TBTF institutions potentially indefinitely. The Minneapolis Plan reverses this approach and gives the Treasury Secretary a new responsibility, with a hard deadline. Within five years of implementation of the Minneapolis Plan, the Treasury Secretary either will certify that large banks are no longer TBTF or those banks will face extraordinary increases in equity capital requirements.

We believe that these automatic increases in capital requirements will lead banks to restructure themselves such that their failure will not pose the spillovers that they do today and thus will not lead to bailouts. We chose the capital level that reduces the probability of a bailout in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries to the lowest level possible while keeping total costs below benefits. This level of capital is appropriate for the largest banks that remain systemically important, as their failure alone could bring down the banking system.

The only banks that could remain systemically important after the Minneapolis Plan has been fully implemented would have 38 percent common equity capital, with a risk of failure that is exceptionally low. Regulators have taken a similar

approach with nuclear power plants: While not risk-free, they are so highly regulated that the risks of failure are effectively minimized. Step 2 of the Minneapolis Plan reduces the chance of a future bailout to 9 percent over 100 years. - Step 3. Prevent future TBTF problems in the shadow financial sector through a shadow banking tax on leverage

The Minneapolis Plan levels the cost of funding between banks subject to a 23.5 percent capital requirement and shadow banks through a tax on leverage on shadow banks larger than $50 billion of 1.2 percent (120 basis points). This tax rate will apply to shadow banks that do not pose systemic risk as certified by the Treasury Secretary. A tax rate equal to 2.2 percent will apply to the shadow banks that the Treasury Secretary refuses to designate as not systemically important. Thus, the

shadow banking tax regime mirrors a two-tier capital regime. These taxes should reduce the incentive to move banking activity from highly capitalized large banks to less-regulated firms that are not subject to such stringent capital requirements. Nonbank financial firms that fund their activities with equity will not be affected. - Step 4. Reduce unnecessary regulatory burden on community banks

Ending TBTF means creating a regulatory system that maximizes the benefits from supervision and regulation while minimizing the costs. The final step of the Minneapolis Plan allows the government to reform its current supervision and regulation of community banks to a simpler and less-burdensome system while maintaining its ability to identify and address bank risk-taking that threatens solvency.

Together, the higher capital requirements on banks and a tax on leverage in the shadow banking system will result in a financial system that is much more stable and poses a substantially lower risk of failure that could lead to a bailout.

- Step 1. Dramatically increase common equity capital, substantially reducing the chance of a bailout

- What will the financial system look like after the Minneapolis Plan has been implemented?

After the Minneapolis Plan has been fully implemented, we expect the financial system to have fewer mega banks and less concentration of banking assets. The banking sector will be much more resilient to shocks because the sector as a whole will be much better capitalized. Any firms that are still systemically risky at that point will have so much capital that their risk of failure will have been truly minimized.

- Is this a breakup proposal?

The Minneapolis Plan does not set a size limit on banks per se, but we fully expect banks facing the higher capital levels in Step 1, and especially those facing the substantial increases in Step 2, to face increased pressure to consider breaking themselves up. Large banks already face pressure from shareholders to reorganize in response to increased regulation. We expect these pressures to increase substantially as a result of the Minneapolis Plan. These banks’ profitability will fall as a result of higher capital standards. In effect, we expect that institutions whose size doesn’t meaningfully benefit their customers will be forced to break themselves up. And when they do, the resulting entities will not be systemically important. However, institutions whose scale provides real value to their customers should be able to maintain their size while being much safer as a result of the substantially increased capital requirements provided by Step 1 or Step 2 of the Minneapolis Plan.

- What types of systemic risk is the Minneapolis Plan addressing?

The Minneapolis Plan is designed to address two types of systemic risk, and Step 1 and Step 2 work in concert to achieve this:

- A systemwide economic shock could hit the entire financial sector, potentially leading to a severe economic downturn. This is essentially what happened in 2008 when the U.S. housing market collapsed and many banks, large and small, were exposed to large losses from their mortgage portfolios. Step 1 of the Minneapolis Plan raises the capital level of all large banks to 23.5 percent to make sure that they have enough capital to withstand such a major shock across the whole system. Like building a wall against a tidal wave, it is impossible to protect against all possible risks. Our analysis suggests that 23.5 percent is approximately the optimal capital level for Step 1 when considering both benefits and costs.

- The failure of an individual institution can pose a systemic risk if that institution is particularly large, interconnected, and important to the financial system. When the capital position of all large banks is increased to 23.5 percent in Step 1, the financial system as a whole will be much more resilient against the failure of any individual firms. In addition, the largest and most complex or most important banks that are systemically risky will be subject to the higher capital requirements of Step 2, up to 38 percent. At these much higher capital levels, these banks will have even stronger incentive to restructure themselves so that they no longer have the potential to trigger widespread economic damage. If the firms choose not to restructure themselves, they will have a large enough capital buffer that their risk of failure is effectively minimized. Again, this is regulation akin to that of a nuclear power plant: If a nuclear power plant melts down, it can cause widespread harm to society. Instead of banning nuclear power plants, the U.S. government regulates them so tightly that their risk of a meltdown is minimized.

Application and Timing of the Minneapolis Plan

- Which financial firms does the Minneapolis Plan apply to?

The Minneapolis Plan applies to bank holding companies (BHCs) located in the United States with assets greater than $250 billion. The proposed shadow banking tax applies to specified firms with assets greater than $50 billion (measured by on-balance-sheet assets, off-balance-sheet assets, and assets under management). We assume that regulations for BHCs with less than $250 billion in assets and shadow banks with less than $50 billion will be unaffected by the Minneapolis Plan, although the Treasury Secretary will have the discretion to review the systemic importance of any financial firm.

- Why have a shadow banking tax?

A shadow banking tax is needed because shadow banks were a significant part of the last financial crisis, and reforms must be a part of any solution. One of the major concerns of new regulations created as a result of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and a concern we share in developing our own proposal is that we might simply encourage activity in the banking system to move to less-regulated shadow banks, such as hedge funds. If the same activity merely moves to other corners of the financial system, has safety been enhanced?

In order to address this risk, the Minneapolis Plan proposes a tax on the borrowings of shadow banks such as hedge funds, mutual funds, and finance companies of 1.2 percent, or 120 basis points, for those certified as not systemically important by the Treasury Secretary. We calculate that this charge is roughly equivalent to having a 23.5 percent minimum capital requirement for shadow banks. The tax will be 2.2 percent for those the Treasury Secretary refuses to certify as not systemically important. We apply these taxes to large shadow banks with assets greater than $50 billion as measured by assets on balance sheet, off balance sheet, or under management. The tax will apply to firms’ nonequity funding—anything other than high-quality common equity. This tax will ensure that all financial firms, including nonbanks, take into account the potential for excessive borrowing to lead to negative spillovers to the rest of the economy and should discourage activity to move from banks to large shadow banks as a result of increased capital requirements.

If risk moves from the largest banks to many small shadow banks, each independently making its own investment decisions, it is very likely that systemic risk will have been reduced. Hence, we apply our new tax only to large shadow banks, those with more than $50 billion in assets, to avoid creating new systemic risks. If large shadow banks do not use leverage to fund their investments, they will not be subject to the new tax.

- Who will the shadow banking tax apply to? Why not insurance companies?

We rely on work of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to identify types of firms that are considered shadow banks. We include:

- Funding corporations

- Real estate investment trusts

- Trust companies

- Money market mutual funds

- Finance companies

- Structured finance vehicles

- Broker/dealers

- Investment funds

- Hedge funds

Our approach does not put insurance firms into the group of shadow banks facing our proposed new tax. Supporting this decision is the view that insurance firms do not engage in the maturity transformation or reliance on short-term funding that typically generates systemic risk. We view additional analysis on the systemic risk posed by insurance firms as useful and important to determining if these firms should be subject to a shadow banking tax.

- Over what time period will the Minneapolis Plan be implemented?

Step 1, the new capital standard of 23.5 percent, and the shadow banking tax will be phased in over a period of five years to give regulated entities time to implement the new regulations. At that point, the Treasury Secretary must certify that individual firms are no longer systemically important. If the Secretary refuses to make that certification, individual banks will be subject to dramatically increasing capital standards and individual shadow banks to the higher tax rate.

Community Bank Reforms

- How will the Minneapolis Plan supervise and regulate community banks?

The focus of our Ending TBTF initiative is addressing the systemic risks posed by large financial institutions. Enacting the Minneapolis Plan for large banks will enable reforms for community bank regulation to proceed. Key features of the proposal to right-size community bank supervision and regulation are as follows:

- Make the capital risk-weighting regime for community banks much less complicated, so that it largely mirrors Basel I.

- Create a default mode for supervision of community banks where supervisors would only review, subject to an exception process, (1) how banks comply with specific laws passed by Congress (and the rules and guidance issued to implement those laws) or (2) operations, policies, or procedures of a bank for which the banking agencies have empirical evidence supporting a correlation with materially weaker bank conditions.

- Impose a wide range of specific risk-focused reforms including but not limited to a longer exam cycle, appraisal reform, reductions in call report collections, and a review of the Current Expected Credit Loss accounting standard.

- Repeal solvency and other noncompliance-related provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act that apply to community banks and that do not have a strong link to their chance of failure.

Legislative and Regulatory Issues

- Will the Minneapolis Plan require new legislation?

Yes. We believe Congress should take action to implement this new Plan. First, the changes we propose are far-reaching and transformational. Ultimately, the public must decide how much safety they want in order to avoid a taxpayer bailout and what cost they are willing to pay for that safety. Congress is the appropriate body to make that determination on behalf of its constituents, rather than regulators. Second, some aspects of the Plan, such as calling on the Treasury Secretary to certify that banks are no longer TBTF and implementing the new shadow banking tax, would require new legislation. Finally, we support codifying the new capital standards into law to make them hard to change.

Societies often forget the lessons of past crises and end up repeating their mistakes. It usually doesn’t happen quickly—oftentimes it is a future generation that repeats past mistakes. The goal of the Minneapolis Plan is to implement a legislative and regulatory system that will allow the U.S. economy to flourish while institutionalizing the lessons from past crises so that future generations don’t repeat past errors. We would not want future policymakers to lower their guard when the economy seems strong.

- What is different about the Minneapolis Plan compared with current regulations?

There are a number of important differences between the Minneapolis Plan and current regulations:

- The Minneapolis Plan does not count debt as a resource to absorb bank losses. Only common stock is counted in the financial cushion that banks can use to absorb losses in the Minneapolis Plan. Other current proposals under which certain debt is meant to take losses in a crisis are problematic because when the crisis indeed hits, policymakers will be reluctant to actually impose losses out of concern that this step would exacerbate the crisis. It is better to rely on equity, rather than debt, to take losses.

- Step 1 of the Minneapolis Plan provides a much higher minimum capital requirement for all U.S. banks with assets greater than $250 billion, 23.5 percent, and it does not vary from year to year.

- Step 2 of the Minneapolis Plan calls on the Treasury Secretary, within five years, to certify that individual banks are no longer systemically important. Absent that certification, banks will face substantially increasing capital requirements, leading many banks to choose to restructure themselves. Current regulations do not force a firm deadline on regulators to decisively address systemic risk.

- The Minneapolis Plan addresses the potential for systemic risk to shift from banks to shadow banks by recommending a new type of tax of 120 basis points on borrowings for shadow banks with total assets above $50 billion (220 basis points for those that remain systemically important following the Treasury Secretary’s certification process). Like the FSB, we count firms like hedge funds, other investment funds, and finance companies as shadow banks. The tax applies only to their leverage, so only firms that borrow to fund their investments would face a tax. No such tax currently exists.

- Finally, the Minneapolis Plan rationalizes the regulations of community banks.

- What elements of current regulations does the Minneapolis Plan propose to keep?

The Minneapolis Plan builds on current efforts to address TBTF, which include higher liquidity standards, new approaches to resolution and recovery planning, and efforts to make derivative markets safer, among many other efforts. The changes we propose are to the capital regime, the determination of whether banks are systemically important by the Treasury Secretary, the implementation of the new tax on shadow banks, and the call for simpler, less-burdensome regulations on community banks. The regulation of banks with assets greater than $10 billion and less than $250 billion will be unaffected by the Minneapolis Plan.

- Why is the risk of a future bailout for current regulations so much higher than for the Minneapolis Plan?

While we and the Federal Reserve System Board of Governors agree that 23.5 percent is a reasonable level of loss absorption for large banks in Step 1, the Board of Governors counts debt as absorbing losses. We do not. Our analysis assumes that in a future systemic crisis, debt will not get converted to equity (as was the case in the recent crisis). Hence, our equity requirement is almost twice as high as required under current regulation, where common equity is set at 13.0 percent and a bailout is triggered as soon as that equity is wiped out. In the Minneapolis Plan, common equity is set much higher, at a minimum of 23.5 percent under Step 1, resulting in a substantial increase in safety and reduced risk of a future bailout.

- Doesn’t the Minneapolis Plan ignore the progress that has been made beyond just capital requirements, for example, in liquidity requirements, stress testing, and resolution?

It is true that progress has been made across a number of fronts, but a requirement for higher capital, the buffer to absorb losses, is the single best tool we have to improve the safety of the banking system. Current regulations acknowledge the need for much higher levels of loss-absorbing capacity, but they mistakenly include long-term debt, which has repeatedly failed to absorb losses in past crises.

BENEFITS AND Costs

- Does the Minneapolis Plan pass a benefit and cost test?

Yes. Assessing benefits and costs of current and potential alternative regulations is at the core of our work to end TBTF. Like terror events, financial crises are hard to predict and hard to prevent. People understand that regardless of how much the United States spends on homeland security, the risk of terrorism can never be reduced to zero. And people understand that increased safety usually comes with increased costs, such as for more law enforcement. The challenge is to find the right balance of safety and costs.

That is our approach to ending TBTF. We want to achieve as much safety as possible while imposing as few costs as possible on the economy. We believe the Minneapolis Plan achieves this balance, but also provides the public with the information they need to make their own assessment of these trade-offs.

- Why is a minimum of 23.5 percent capital the right level for large banks?

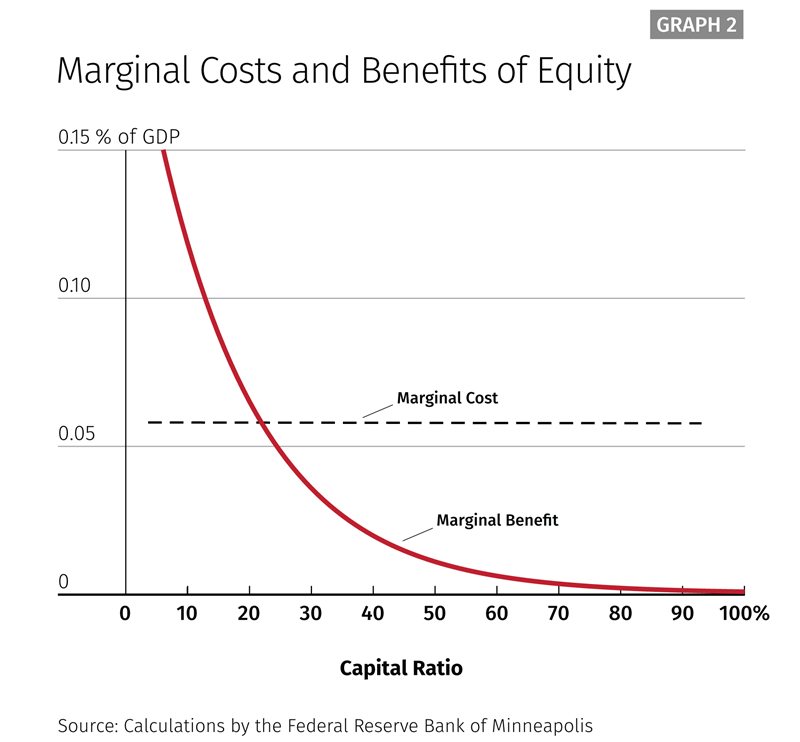

We studied analyses from the Board of Governors, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the FSB, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and leading academics as well as conducted our own analysis. Based on the data and analyses available, we determined that a capital level around 22 percent maximizes net benefits to society, considering the benefits of safety and the costs of slower economic growth. Graph 1 reports the marginal costs and the marginal benefits of increasing capital. We assume that costs increase with increased capital levels due to higher borrowing costs in the economy. We assume that benefits increase with a reduction in the probability of a future financial crisis. We chose the precise number of 23.5 percent based on the Board of Governors’ proposal—which is now a final rule—for the amount of loss-absorbing capacity the most systemically important banks must have. We believe their analysis is reasonable and have adopted it as our minimum capital requirement in Step 1.

- Won’t such high capital levels hurt economic growth?

We believe the cost of higher capital is low compared with the benefits of increased safety. Our analysis suggests that the total costs to society of the Minneapolis Plan are approximately 24 percent of GDP for Step 1, whereas the cost to society of a typical financial crisis is approximately 158 percent of GDP. The Minneapolis Plan will have paid for itself many times over if it avoids one financial crisis.

- How does the Minneapolis Plan calculate the costs of these regulatory changes?

We use the same method used by the BIS to estimate costs. This method recognizes that more capital is costly. The higher cost shows up as higher loan rates for borrowers. This reduces lending and investment, which lowers GDP. We estimate this cost through our own calculations and using the Federal Reserve’s model of the economy, FRB/US.

- How does the Plan calculate the risks of future bailouts?

As it is for natural and man-made disasters (such as earthquakes and terrorist events), it is difficult to predict financial crises or even estimate their likelihood or severity. All regulators who want to limit future bailouts must rely in part on the historical experience with these rare but costly events. And we look to these data as well.

While we considered work from regulators and academics around the world, we focused on analysis from the IMF, which reviewed data on past banking crises, public bailouts, and capitalization levels of various banking systems. We are the first to admit that this is an imperfect science, but we believe our approach is sound and relies on the best data and analyses available.

- Why doesn’t the Minneapolis Plan reduce the chance of a future bailout below 9 percent?

Capital in large banks is the equivalent of building a wall to protect against a tidal wave. Societies have to decide how high a wall to build and how much they can afford to spend to protect against a possible future flood. We believe the Minneapolis Plan offers an appropriate balance of safety at a reasonable cost. Ultimately, the public needs to decide how much safety they are willing to pay for.

We set our goal to reduce the chance of a future bailout to less than 10 percent, which requires a capital level up to 38 percent, where total benefits to society still exceed total costs. Increasing capital levels further could push the bailout odds lower still, but total costs will exceed the benefits at some point.

Moreover, some leverage in the financial system is useful. After all, banks are in the business of transforming borrowed funds, including deposits, into loans. We are proposing a considerable increase in equity funding in the financial system, but not a system funded entirely with equity, as some experts have proposed.

- Why does the Minneapolis Plan impose a 23.5 percent equity capital requirement in Step 1 on banks larger than $250 billion when those banks had to have been certified by the Treasury Secretary to not be systemically important in order to avoid Step 2? If they aren’t systemically important, why impose Step 1 at all?

Banks that are only subject to Step 1 will no longer be systemically important because many will have responded to the threat of the higher capital standards of Step 2 by lowering their own risk so that they are not TBTF and can earn the Treasury Secretary’s certification and remain in Step 1. They will do this by shedding assets and restructuring their business lines so that their failure cannot inflict systemic harm on the banking sector. But the potential for an individual bank to trigger systemic damage is not merely a function of that individual bank’s assets and liabilities; it is also a function of the strength and capital position of the rest of the banking sector. For example, if an individual bank with $250 billion in assets failed when all other banks with $250 billion or more assets had at least 23.5 percent capital, we believe such a failure would likely not pose a systemic risk. However, if that individual $250 billion bank failed when all other large banks were lightly capitalized, that failure might pose a systemic risk. Hence, the minimum 23.5 percent capital requirement for all large banks is essential to enabling individual firms to make themselves no longer TBTF.

- What happens if a crisis hits that is so large that even the higher capital level in the Minneapolis Plan is not enough?

Unfortunately, it is impossible to know just how big an economic shock the U.S. economy may face in the future. Just as it is impossible to design a building that can withstand an earthquake of unlimited intensity, it is impossible to completely eliminate the possibility of a future bailout. Our experience and analyses suggest that if the capital in the banking system is wiped out due to massive losses, the government will likely have to step in with some form of bailout, as it did in 2008. That should be far less likely under the Minneapolis Plan than under current regulations but, in either case, if losses exceed capital for many large banks at the same time, we believe policymakers will need to turn to taxpayers to support the financial system. As in 2008, the costs to Main Street if the financial system were allowed to collapse will likely far exceed the cost of a bailout.

- How will the Treasury Secretary determine that banks no longer pose systemic risk in Step 2?

Regulators around the world use a common approach to measure the systemic risk of banks when it comes to setting the capital that these banks must issue. Specifically, this common approach is used to set the “systemically important financial institution capital surcharge.” These metrics reflect the regulatory state of the art today. The Minneapolis Plan calls on the Treasury Secretary to look to this measurement approach used by many regulators in making the certification that a bank does not pose systemic risk, but would not limit the Treasury Secretary’s assessment to this one approach. Banks would face automatic, substantial increases in their equity capital requirements unless the Treasury Secretary deems them no longer systemically important. We believe that banks facing such increasing capital standards will likely restructure their operations such that they no longer are systemically important and thus do not have a material chance of needing a bailout.

- How did the Plan determine the maximum capital level of 38 percent in Step 2?

One of the goals of the Minneapolis Plan is to reduce the chance of a future bailout to less than 10 percent. We set the maximum level of capital at 38 percent to achieve that goal, while also ensuring that total benefits exceed total costs to society as shown in Graph 2.

Important Considerations

- Why isn’t debt counted as capital in the Minneapolis Plan?

We learned from past financial crises, including the 2008 crisis, that nothing beats equity for absorbing losses. Equity holders have long taken losses in the United States and thus expect that outcome. Moreover, equity holders cannot run during a crisis. In contrast, debt holders of the most systemically important banks in the United States and around the world have repeatedly experienced bailouts and likely will expect such an outcome during the next financial crisis. Indeed, the most recent crisis showed that even some debt holders who had been explicitly told that they would take losses during a crisis got bailed out.

Governments are reluctant to impose losses on debt holders of a TBTF bank during a crisis because of the risk of contagion: Debt holders at other TBTF banks may fear they will face similar losses and will then try to pull whatever funding they can, or at least refuse to reinvest when debt comes due. This is why, regardless of their promises during good times, governments do not want to impose losses on debt holders during a crisis. History has repeatedly shown this to be true and, while we can hope for the best, there is no credible reason to believe this won’t be true in the next crisis. Only true equity should be considered loss-absorbing in a crisis.

- Won’t long-term debt be less costly than equity in terms of economic growth?

Some proponents of the current regulatory framework argue that since long-term debt is cheaper than equity for banks to issue, it will therefore have a smaller impact on lending rates for borrowers and, hence, economic growth compared with issuing more equity. Yet these same regulators argue that this long-term debt really will face losses in a crisis. In other words, they argue that investors will misprice these securities, demanding small compensation for the risk they are taking. Over time, such mispricing is unlikely to be sustained. Either the securities really will face the risk of losses (in which case they will be priced more like equity—providing little benefit in terms of economic growth) or the securities really won’t face losses, in which case they are not useful for preventing financial crises and bailouts. Counting on long-term debt to be both loss-absorbing and low cost is simply not credible.

- Isn’t long-term debt superior to equity by allowing for recapitalization of failed banks?

Some regulators have argued that long-term debt is critical to giving them additional financial resources to recapitalize a bank once it has failed and gone through the resolution process. They worry that a bank issuing more equity will have no funds left to recapitalize it post-resolution. All the equity, they argue, would be gone by the time the bank goes into resolution.

This is not an argument in support of issuing more debt. Instead, it is an argument for closing banks before they are totally insolvent. Regulators could close banks with low but still positive equity. Such a system would leave regulators with the same financial resources they have today with none of the complexity and uncertainty of the current regulatory framework.

- The Minneapolis Plan will likely reduce the number and size of large banks. Aren’t large banks needed for a strong economy?

Large global banks add value to the economy by providing services that small, regional banks cannot. However, the benefit of large banks comes with extraordinary risks of financial instability. The Minneapolis Plan assesses the benefits and costs of large banks and of increased safety. We attempt to achieve the appropriate balance that will allow the U.S. economy to flourish without taking unacceptable risks.

- Don’t bank supervisors already have to reduce the systemic risk of the largest banks to immaterial levels?

No. While regulators are working to reduce systemic risk, they never have to formally make the certification that banks are no longer systemically important. As a result, banks may be able to enjoy their explicit or implicit TBTF status potentially indefinitely. It is true that supervisors, through the living will process, have to determine if BHCs can effectively go through the commercial bankruptcy regime. Moreover, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) can potentially act if a firm poses a grave threat to the financial stability of the United States (but only after a series of votes at the FSOC and the Board of Governors). However, there is no mandate that regulators must act. In contrast, the Minneapolis Plan forces the government to certify that banks are no longer systemically important within five years of the Plan’s implementation.

- Why not reintroduce Glass-Steagall?

By itself, Glass-Steagall would not have prevented the 2008 crisis, and we doubt that it would prevent a future crisis. It is true that a reintroduction of Glass-Steagall would likely result in somewhat smaller and less-complex financial institutions, but we do not believe it would substantially reduce systemic risk or the risk of a future taxpayer bailout. Many banks whose activities were restricted to either the commercial or the investment banking sectors ran into trouble in 2008, illustrating that trouble was not limited to firms engaged in both types of operations. Increased capital levels are much more likely to improve the safety and soundness of the U.S. financial system than a reintroduction of Glass-Steagall.

- Why not just put the big banks in a form of bankruptcy and/or the resolution system set up by Dodd-Frank?

A bankruptcy-based approach does not credibly reduce the risk of a bailout. Bankruptcy and the new resolution system under Dodd-Frank rely on imposing losses on creditors during a crisis to prevent a bailout. The debt becomes a source of equity for the firm leaving reorganization. As previously explained, we do not think that is a credible option for the largest, most systemically important banks, because it may lead to contagion to other banks and potentially trigger widespread economic damage. Bankruptcy and the Dodd-Frank resolution system should be viable options for banks that emerge after implementation of the Minneapolis Plan because they will likely be smaller, less complex, and safer.

- New proposals have come out from Congress and the Trump Administration. How do those proposals compare to the Minneapolis Plan?

The House of Representatives passed the Financial CHOICE Act on June 8, 2017. The Treasury Department released “A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunity: Banks and Credit Unions” on June 12, 2017. Each includes some measures to try to reduce the risk of financial crises and bailouts, among a wide range of other provisions. The Financial CHOICE Act would create an “off-ramp,” allowing banks with a leverage ratio of 10 percent to not face a host of banking regulations, such as the Comprehensive Capital Assessment and Review (i.e., the “stress test”) and post-financial-crisis liquidity rules. The Treasury report is less definitive, suggesting the consideration of such an off-ramp and referencing, by example, a higher leverage ratio of 10 percent.

Our analysis indicates that a 10 percent leverage ratio would only reduce the odds of another financial crisis in the next 100 years to 50 percent, which we believe is far too high. We also do not support the “off-ramp” approach. We believe banks will not take the off-ramp, resulting in no reduction in risk for taxpayers from current high levels. The Minneapolis Plan is far more aggressive in addressing TBTF than either the CHOICE Act or the Trump Administration’s regulatory proposal. Our recommended leverage ratio, if measured in the same way as the CHOICE Act, is 33 percent higher.

- Why not just wait until the next crisis and implement another TARP program?

Some experts have argued that preventing financial crises is too costly and that it may be cheaper to address the problem once it happens. They argue that increasing capital standards requires society to pay every year with slightly lower economic growth and that perhaps the economy would be better off with a higher growth rate between crises. We believe the Minneapolis Plan will allow the economy to enjoy strong growth with fewer and less-severe financial crises than the current regulatory framework. Ultimately, the public must decide whether they want to prevent financial crises or clean up after them. And if cleaning up after a crisis is indeed the preferred approach, uncertainty remains as to whether future legislators would approve another TARP program.

In 2008, policymakers and Congress had no choice but to deal with the crisis once it began. Even though the direct fiscal costs of the TARP program were very small compared with the size of the U.S. economy, the cost of the crisis was nonetheless devastating for Main Street. We think our regulatory system can and must do better.

- Since the Minneapolis Plan draft was released in November 2016, several analytical studies have been released assessing benefits and costs of higher capital standards. What do they conclude?

Many economists have published studies in 2017 assessing capital standards for large banks, and nearly all of their analysis supports the higher equity levels that we recommend (23 percent range or even higher on a risk-weighted asset basis or 15 percent on a leverage basis). This result is powerful precisely because these economists do not use our methodology, but come to the same conclusion. Chair Janet Yellen (2017) summarized some of this same research recently, noting that “this research points to benefits from capital requirements in excess of those adopted.” We summarize this analysis in more detail in our accompanying comment and response document (see Comment/Response 15). In total, these studies highlight a growing consensus among experts that capital standards for large banks should be raised to protect taxpayers.

References

U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2017. A Financial System that Creates Economic Opportunities: Banks and Credit Unions. Available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/A%20Financial%20System.pdf.

Yellen, Janet L. 2017. Financial Stability after the Onset of the Crisis. Remarks at “Fostering a Dynamic Global Recovery,” a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyo., Aug. 25. Available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20170825a.htm.