"Bleak."

That's how Roger Olson described conditions over the last decade in the small town of Chester, Mont., and the entire region fondly called the Hi-Line after the 475 miles of railroad track that run across the northern part of the state. The track set in place the many small farm-and-rail-hub towns that dot that part of the state. Olson has lived and sold health insurance in Chester since 1998, but "I've lived along the Hi-Line all my life."

The city saw its population drop by 71 people during the 1990s and is home today to 871 people—still a big city in Liberty County, where the population decreased by 6 percent (about 140 people) and stands at just 2,158.

These are tough times in Liberty County. Farming is in the dumps, thanks to low wheat prices and a persistent drought that has decimated ranchers. Per capita income during the 1990s dropped by almost 3 percent. Twenty years ago, Chester had three farm implement and three auto dealerships. The last of each has closed shop in the past three years. That's bad news for Chester, "because now there's no reason for farmers to stop [in town] anymore," Olson said. Instead, they'll drive the 90 miles to Great Falls for their farm needs, "and I'll bet that pickup will be full of groceries too."

Olson is the head of the local chamber of commerce and has been banging on the door of change, saying that if Chester and other Hi-Line communities don't pursue some new strategies, "the worm will not turn. It will only get worse."

Liberty County is one of many struggling rural counties in the Ninth District. According to the 2000 census, almost 90 percent of North Dakota counties lost population during the 1990s. So did most of the eastern counties in Montana, half of South Dakota counties and most of the southwest region of Minnesota.

At the same time, most metropolitan counties in district states are thriving. (Metropolitan counties are so-designated when one of its cities has a population of 50,000 or more, or if it is part of an urbanized area with a population of 100,000 or more. These counties are said to be part of a metropolitan statistical area, or MSA.)

Cass County, home to Fargo, N.D., saw its population increase by 22 percent; the populations of Minnehaha and Lincoln counties, home to Sioux Falls, S.D., increased 20 percent and 56 percent, respectively. Both the Twin Cities and Rochester regions grew by 17 percent. The Twin Cities metro alone added better than 410,000 people, or about 80 percent of the state's population growth.

Such a contrast makes for compelling news stories. Small towns are dying, and generations lost, while big cities vacuum up rural folks who are simply looking for opportunities no longer available in rural America.

Or so the story went. One has to look long and hard for much positive news regarding the long-term outlook for rural areas. Media coverage of the 2000 census often implied that rural areas were doomed to fade quietly, but inevitably.

Well, are they?

If one looks only at population trends and is content to compare urban and rural counties to each other, then yes, rural areas are squarely behind the eight ball in many socio-economic comparisons.

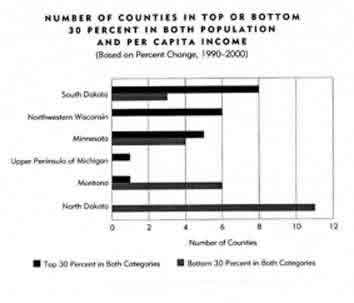

In an effort to get a glimpse into rural demographics but also consider a broader measure of well-being, fedgazette looked at how the district's 274 rural (or non-MSA) counties compared with each other in two key statistics: percentage change in population and per capita income during the 1990s.

Counties were ranked in each category, and those counties scoring in the top and bottom 30 percent in both categories were then targeted for further analysis. In all, there were 21 rural counties in the district that ranked in the top 30 percent in each category; 24 counties scored in the bottom 30 percent (see "What's Under the Performance Hood" with county listing and discussion of the methodology employed).

These top- and bottom-performing groups reinforce the notion that many rural counties are facing truly critical times. But the rankings also indicate that some counties are holding their own, even thriving.

The right stuff

In an attempt to glean some insights from the top- and bottom-performing counties, fedgazette took a closer look at what commonalities and differences exist between the two groups. The search floated a few factors to the surface (see accompanying summary table ).

-

Bigger is better. Top-performing counties have much larger average populations, were more likely to have a city of at least 5,000 people and have more large employers than bottom counties.

-

Location matters. Top counties were more likely to be located near faster-growing metro regions, usually capturing some of the spillover. So too were top counties more likely to have an interstate rolling through it.

-

Manufacturing trumps farming. Top-performing counties were more dependent on manufacturing, while bottom-performing counties derived a larger-than-average share of personal income from farming.

-

Bet on growth. Top counties were more likely to be the home of a Native American casino.

To be sure, some factors that correlate positively with top-ranked counties are a bit self-evident, even self-reinforcing—like the coincidence of having larger populations, more cities of at least 5,000 people and more large employers.

But not all top-ranked counties had a city of 5,000 (only one-third did), and after factoring for population size, top-ranked counties still had significantly more large employers. Such findings suggest that population clearly influences a county's performance, but does not do so in isolation.

How big is yours?

One of the clearest differences in top- and bottom-performing rural counties was their population size. On average, top counties had fourfold more people than bottom counties. Top counties also were smaller geographically, which means their population density was even more pronounced—sixfold higher than bottom counties.

Top-rated counties also had more cities with at least 5,000 people. Despite negative connotations widely attached to city-living—too crowded, too noisy, too smelly—the 2000 census demonstrated that cities big and small-but not too small-were growth magnets.

There are more than 100 cities in Minnesota with a population over 5,000, according to the State Demographic Center. Collectively, they averaged 14 percent growth in population during the 1990s. Fewer than one in five lost population. That was not the case for small cities. Minnesota has almost 650 cities with fewer than 2,500 people. Collectively, their population grew at a much slower 6 percent, and better than 40 percent lost population.

In a similar vein, fedgazette research indicates that even comparatively small cities acting as regional economic hubs were important sources of growth for rural counties. Among top-rated counties (all of which saw population growth), one in three had a city of at least 5,000 people; among bottom-rated counties, it was fewer than one in 10.

One such case was in Brookings County, S.D., where the population grew by 12 percent in the 1990s and per capita income increased better than 70 percent, ranking it well within the top 30 percent of both categories. The engine of that growth was the city of Brookings, which was responsible for three-quarters of the county's population growth and a disproportionate number of new jobs.

According to Scott Munsterman, owner of Brookings Chiropractic and a city councilmember, the city acts as an "anchor" for the rest of the county, offering good jobs, a sizable labor pool for employers, cultural and recreational amenities and a range of retail and commercial services.

"Part of it has to do with [Brookings'] attitude" toward growth, demonstrated in the fact that the city dedicates almost 10 percent of its annual budget to growth and development efforts, Munsterman said. The city owns a fair amount of land, which means it can "cut good deals for businesses" looking to relocate.

The city has built a new ice arena and is working on a fine arts center, which makes life for current residents more enjoyable, but is also intended to make Brookings more attractive to people looking for a place to settle down.

"I think we're at a critical juncture. It all hinges on what you can offer people," whether it be job opportunities, good schools or a better lifestyle, Munsterman said. If the city doesn't continue its pursuit of becoming a high-amenity location, according to Munsterman, "we could become one of those dying communities. But I don't think that's going to happen."

One of the big draws for Brookings is South Dakota State University, and in fact, presence of a university or college had a positive correlation for top-ranked counties in general. Along with substantial employment—including many good-paying, stable teaching jobs—higher education institutions bring numerous other benefits to the local community.

"The college brings in culture," said Munsterman. It also brings about 8,000 college kids to town, which offers local businesses a ready-made supply of high-skilled workers. "Our job as city leaders is to keep them here."

Big brother—both good and bad

Rural counties also tended to fare better in the rankings if—or more likely, because—they were located near metro regions.

Union County, S.D., for example, is sandwiched unevenly between Woodbury County, Iowa—home to the Sioux City region—and Lincoln County, S.D., to the north, which in 2000 was designated as part of the Sioux Falls MSA.

Most of the growth in Union County was "bottom heavy," as one local source described it, growing north from Sioux City, which is seeing a modest rebound of sorts after two decades of farm and industrial difficulty. While Union County's population growth was strong (almost 24 percent), what really set it apart was the 108 percent increase it saw in per capita income, fueled by incredibly strong job growth in high-paying sectors.

Much of that growth settled in Dakota Dunes, a planned community less than 10 minutes from Sioux City that has become one of South Dakota's most well-to-do enclaves. Less than 2,000 acres in size, the community—it is not technically a municipality—did not exist when the 1990 census was taken. Back then, the area now called Dakota Dunes "was just a few farm houses," said Jeff Dooley, district manager of Dakota Dunes Community Improvement District.

But over the past decade, that farmland has grown a rich crop of jobs and houses. Union County's population went up by 2,400 people, and 2,000 of them landed in Dakota Dunes. In the community's marketing material, a new couple gushes, "Because everybody's so new here, everybody wants to get to know everybody else."

The county also added 7,500 jobs during the 1990s, an increase of better than 150 percent. Dakota Dunes is home to 1,600 of those jobs, and 500 more are expected with the recent expansion announcement by Premier Bankcard. The community has a large medical campus and is a corporate headquarters of the former meatpacker IBP, which was bought out by Tyson last year. The community is also just up the road about a mile from North Sioux City, S.D., the former headquarters of Gateway Computers before it relocated to San Diego. The company still employs almost 3,700 in major manufacturing operations there.

All those high-paying jobs are reflected in the property value of Dakota Dunes, which has gone from just $2 million in 1990 to $172 million in 2001. "It's starting to snowball," Dooley said regarding new development. The average house value in Dakota Dunes is $245,000, based on sales in 2001. There is no housing under $100,000.

But being next to a metro county is not always sugar and spice. Nearly 30 percent of bottom-ranking counties bordered an MSA county. The difference appears to depend on whether a county still acts as a "population feeder" and sees net out-migration to a metro region, or is close enough from a development standpoint that it sees spillover growth as a metro area expands and people look for cheaper land to build houses and locate new businesses.

Lincoln County, S.D., saw the fastest growth of any county in the district at 56 percent, or almost 9,000 people. Most of its growth—going back to 1980, in fact—is attributable to the fact that Lincoln County has become a bedroom community to an expanding Sioux Falls region. But that proximity hasn't always helped the county. From 1930 to 1970, the county lost 15 percent of its population (more than 2,000 people) before rebounding strongly in each of the last three censuses (see additional discussion).

Down on the farm

For the most part, counties that performed poorly were more notable for traits that were absent than traits that were present. The one exception was the dependence of these counties on farming.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Economic

Analysis

Bottom-rated counties earned almost 18 percent of total personal income from farming in 1990, according to figures gleaned from the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). In contrast, only about 4 percent of personal income in top-rated counties came from farming. As a result, when the farm downturn hit in the 1990s, bottom-rated counties generally got hammered while top-rated counties got by with a few scrapes, thanks mostly to gains in other sectors that more than offset difficulties in farming.

Consider Nelson County, N.D. In the 1990s, it lost 16 percent of its population, falling to just 3,715 people. The county's per capita income went up an anemic 15 percent, well below the rate of inflation.

Situated in the eastern part of the state between Grand Forks and Ramsey counties—home to the cities of Grand Forks and Devils Lake, respectively—Nelson County has no real regional center. Lakota, the county seat, has been losing population since 1960 and has just 898 residents, yet is still twice as big as any other town in the county.

Here, everything starts with agriculture. Or maybe more accurately, everything has stopped with agriculture. In 1990, farming was responsible for a little more than 25 percent of personal income in Nelson County, according to figures from the BEA. Then came the farm setback.

The nationwide downturn in the farm economy started around 1997. But in Nelson County, the crisis started already in 1993 "when it started raining and it never quit," said Bruce Anderson, president of the State Bank of Lakota. He means that literally. Anderson said that about one-quarter of the farmable land is perpetually under water, and the local economy has struggled for the last decade.

In 1990, farming in Nelson County brought $21 million in income. (Farm income is calculated after expenses and does not include government payments. Neither does it include secondary income effects, like local income derived from the production or sale of, say, tractors.)

Low prices and other pressures have been compounding to the point that the county reaped less than $50,000 in farm income in 2000. During this time, the nonfarm economy in Nelson County grew almost 30 percent, but that was not enough to offset farming losses, and the county's total economy (as measured by total personal income) shrank about 4 percent.

Both Anderson and his bank are exceptions in Nelson County. Despite being a farm lender, the State Bank of Lakota has managed to remain "fairly stable," Anderson said. The number of borrowers has decreased, "but they are bigger loans" as farm size increases.

Anderson himself is a Lakota native who went away to college in Texas and took his first job in Minneapolis working for an accounting firm. But in 1989, he returned to Lakota to work at the bank, which his family has owned since 1946. But Anderson is the demographic exception in Lakota. "The average age of the population is way high, and young people are not hanging around," Anderson said. "There is no economic opportunity." He said he still talks with old friends who live elsewhere. "A lot of them would move back for a viable economic opportunity."

Still, Anderson and others hold out hope. "What's the future of the area? That's tough to say." Anderson said. "I'm an optimistic person. If I wasn't we'd have sold out and moved on long ago."

Lakota has high-speed Internet access and, over the last five years, has managed to overhaul its road, sewer and water infrastructure. It also updated its golf course and built a new community center, in hopes of marketing itself as a bedroom community to Devils Lake, which is about 25 miles to the west. "That's the way we can position ourselves for growth," Anderson said.

But the county is swimming against a strong current. Research by John Fraser Hart, a geography professor at the University of Minnesota, has shown that the last decade "was a continuance of existing trends" in many rural areas that "have been losing population for half a century." Nelson County, in fact, has been losing population steadily for 80 years, and today has about 36 percent of the population it had in 1920.

The reason, Hart said, is that many rural counties are dotted with small towns that were developed as supply outposts for farmers. Steady and significant improvements in farm productivity have sliced labor needs dramatically, and many small towns "have not developed any alternative economy" to replace the lost jobs and income for these workers, said Hart, who's been studying small town population trends for the better part of a five decades.

"What's taking the place of [farming]? Nothing," Hart said. As a result "there's a tremendous redundant population," and many people leave for better opportunities.

Manufacturing, big employers

Top-ranked counties, on the other hand, appear to have made that transition to a nonfarm economy. With just a small fraction of income coming from farming, the farm crisis has brought much less shock to these counties' economies.

Indeed, one of the more counterintuitive findings was the strength in and dependence on manufacturing among top-rated counties, and the virtual absence of manufacturing in the economies of bottom counties.

Manufacturing as a percentage of the economy has been slipping for a number of years as other sectors, particularly services and retail trade, gain prominence. But manufacturing nonetheless appears to be an important stabilizer for top-rated counties, which had much higher manufacturing employment (13 percent) than bottom counties (only 3 percent).

In many cases, manufacturing employment hasn't been in decline so much as it hasn't been growing as fast as other sectors. For example, manufacturing jobs made up 15 percent of employment in Minnesota in 1990. Despite adding better than 40,000 more manufacturing jobs over the next 10 years, the sector's portion of total employment fell more than a point and a half.

Given the decline in farming, manufacturing appears to offer a solid base of good-paying jobs, particularly compared with the two fastest-growing employment sectors of retail trade and services. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), average manufacturing wages and benefits were almost 13 percent higher than average jobs in the service sector and more than double the compensation of retail trade jobs.

Extensive research also shows that company size and wages are related—the bigger the company, the better the wages. Almost on cue, top-rated counties were shown to have significantly more large employers (companies with more than 250 workers) than bottom counties, even after factoring for population size.

A human resource manager at a large employer in northern Minnesota said, "I think the scale [of a large company's employment] brings a certain level of wages and benefits" that smaller companies can't often match.

BLS data confirm that notion. Average wages at companies with fewer than 100 employees was $13.88 per hour as of March 2002; firms with 100 to 499 employees paid their workers almost $2 more an hour, and companies with more than 500 employees paid their employees an average of $20.79 an hour. They also offered much higher benefit levels, including better paid leave, insurance and retirement benefits.

Higher wages and benefits are good for workers but also good for the local community. According to a human resource manager of another large employer in northern Minnesota, "The [higher] wages and benefits really create a much more stable community. People can afford to buy a house."

The road to growth

Mobility and access have always been a key factor in growth patterns nationwide, going back to waterways, steam engines and railroads. So not surprisingly, interstate highways were found in top-performing counties at more than twice the rate of bottom counties.

In South Dakota, Interstate 29 plays connect-the-cities, starting on the southern border with the Sioux City, Iowa, region and climbing north through Sioux Falls, Brookings and Watertown on its way to Fargo, N.D. Along the way, it runs through three top-rated rural counties, each of which is home to regional centers or major employment hubs.

Interstate 94 runs through Dunn County, in western Wisconsin, and is an integral part of the local economy because it connects the county and its largest city, Menomonie, to both the Eau Claire and Twin Cities metros, said Gene Smith, administrative coordinator for the county. "We are also in direct line between Minneapolis and Chicago."

The county is seeing strong growth as a distribution hub from both new businesses and expansion of existing ones, like Wal-Mart, which is doubling its existing distribution warehouse in town, Smith said.

But an interstate highway is not necessarily the yellow-brick road to prosperity. For example, Interstates 90 and 94 roll through much of the district and link a number of the district's growing metro areas. Both enter the eastern part of the district in Wisconsin, slowly separating from each other as they stretch across Minnesota and the Dakotas, and then slowly nearing each other again in Montana until finally meeting in Billings. Here, I-94 ends, and I-90 continues across the state and then jogs north toward upper Idaho.

In all, the two interstates lay asphalt through about 50 rural counties in the district. Yet only three counties along these interstates were among the top performers—the same number that also made the bottom list. Neither were there any top (or bottom) counties along I-15 in Montana, and only one top-performing rural county along I-35 in Minnesota.

"It probably relates to other issues," Smith said regarding the influence of interstate highways. For example, Smith grew up in Albert Lea in southern Minnesota, a city in Freeborn County that is dissected by two interstate highways (I-90 and I-35) yet has not seen the gangbuster growth one might anticipate. One reason might be more favorable workers' compensation laws in Mason City, about 25 miles over the Iowa border, Smith said. "The interstate provides the avenue (for growth), but there are a lot of other factors."

Casinos improve odds

Especially among isolated rural counties, nothing seems to have influenced county performance quite like the presence of a Native American casino. Almost three of five top-performing counties had such a casino within its borders, while fewer than one in 10 bottom counties did.

Mackinac County, in the very eastern part of Michigan's Upper Peninsula (U.P.), is an area known for summer tourism, thanks to the fact that the county's entire southern border looks out over Lake Michigan. The county seat of St. Ignace, which hugs the Mackinac toll bridge linking upper and lower Michigan, has a population of about 2,700.

"It swells dramatically during the summer," said James North, president and CEO of First National Bank of St. Ignace, "and in winter things shrink back to reality."

But more people are deciding to call it home. During the 1990s, Mackinac County saw its population increase about 12 percent to almost 12,000. Equally notable, per capita income jumped 64 percent, to about $25,000.

One likely source is the county's two Kewadin casinos, one in St. Ignace and a small gaming outpost in tiny Hessel, about 30 miles further east, both owned and operated by the Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians.

North said the casinos "have created a lot of employment and served to flatten out" the summer-heavy economic activity in the county.

Michelle Litzner, public relations director for Kewadin Casinos and a tribal member, agreed the casinos have brought more year-round activity to St. Ignace and surrounding areas. "Before the casino, you could shoot a shotgun down the street and not hit anyone."

The St. Ignace casino opened in 1988 with just 4,000 square feet of gaming. In 1996, 27,000 square feet of gaming and office space were added, and another 25,000 square feet were added several years later, according to Litzner. Kewadin employs 341 people at St. Ignace and 37 more in Hessel. It also operates three other gaming venues in nearby counties that employ another 900. They are a big reason Mackinac saw its unemployment rate drop from almost 15 percent in 1990 to under 9 percent a decade later.

Litzner said the pristine surroundings of Mackinac County help the casino draw customers. "The things that set us off [from other casinos] are the amenities," Litzner said. But it works both ways. The casino promotes other area attractions in its own marketing material to help spread tourism spending among local businesses.

The tribe has also invested heavily in new housing, community centers and health facilities for tribal members and contributes 2 percent of its earnings from slot machines to local governments in the tribe's seven-county service area. Annual payments are about $2 million, and to date the tribe has contributed close to $16 million.

But the casinos do have a downside, according to North, pointing out that his bank has been seeing "record" personal bankruptcies. Litzner also acknowledged that the market for casinos is also pretty saturated and competition is fierce among the state's 20 casinos, more than half of which are in the UP As a result, the dramatic local impact of casinos "is going to level off eventually," Litzner said. "You can only tap [tourist gamblers] for so much."

Intangibles

In some cases, none of the variables investigated were good predictors of a county's performance.

Take Butte County, S.D. Set on the western border with Wyoming and a small piece of Montana, Butte looks fairly indistinguishable. A large county with a small population (just 9,000), it has a population density of just four people per square mile—exactly the average density for bottom-performing counties. Neither does it have a city of more than 5,000 people, nor an interstate highway nor a single large employer.

But things are looking up in Butte. Population increased a solid 15 percent during the 1990s, and per capita income jumped some 60 percent to almost $20,000. It's a full county away—about 50 miles—from Rapid City.

A closer look would show that Butte comes horseshoe-close on two related variables analyzed by fedgazette. I-90 comes within a whisker of the county border and makes a beeline for Rapid City, passing a number of smaller cities along the way.

According to Todd Keller, mayor of Bell Fourche, the county seat, that proximity has allowed the city to play bedroom community for workers in Spearfish, Lead, Sturgis and even Rapid City.

"We're a little cheaper, and I think we have a friendlier community," said Keller, who is also a lab manager for a local health care center. As a result, Belle Fourche (pronounced bell-FOOSH) grew to 4,500 people in the latest census.

But it's more than a freeway that brings people to town, Keller believes. "The biggest attribute of our community is the volunteers." The city's annual Round-Up celebration over the July 4 holiday brought an estimated 27,000 people to town, some from as far away as Arizona and Oregon, Keller said. The event is run entirely by volunteers.

"That's the glue of this community. They don't ask for anything. They just want to make the community better," Keller said. "Everybody pitches in. ... It doesn't matter what walk of life you're from."

Research for this project was contributed by Tobias Madden, regional economist; Rob Grunewald, regional economics analyst; and research assistants Nik Grezda and Nisha Lima. Additional research was provided by St. Olaf College students Elizabeth Holmes and John Palmer, under the supervision of Terry Fitzgerald, St. Olaf economics professor and Minneapolis Fed consultant.

Related articles: |

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.