Imagine an unretired Bob Barker hosting a new show called the Health Care Price Is Right. Barker asks contestants to name the price of an ear tube insertion at a hospital in Wisconsin—a common outpatient procedure often done on kids suffering from repeated ear infections. Last year, almost 3,400 of these procedures took place statewide.

Any guesses on how much one costs? $1,300? $2,000, $3,000? $4,200? You'd be a winner guessing any of these, because various Wisconsin hospitals charged (roughly) each of those prices for ear tube insertions last year, according to data collected by the Wisconsin Hospital Association.

Any guesses on how much one costs? $1,300? $2,000, $3,000? $4,200? You'd be a winner guessing any of these, because various Wisconsin hospitals charged (roughly) each of those prices for ear tube insertions last year, according to data collected by the Wisconsin Hospital Association.

Maybe you live in Eau Claire County and want to narrow the field—and price range—to four hospitals there. Sorry, but prices still go from $1,700 to almost $4,200. Think it's cheaper in Minnesota? Guess again, according to data from that state's hospital association. The median charge for ear tube insertions at Minnesota hospitals—about $3,000—was 66 percent higher than the median charge in Wisconsin of about $1,800.

Not only are prices for the operation all over the map; none of the above figures is the full cost of the procedure in either Wisconsin or Minnesota, because the prices cited don't include professional fees for doctors or surgeons doing the procedure. So none of those prices gives you a very good idea of the total cost for the ear tube procedure, start to finish. Said Twila Brase, president of the Citizens' Council on Health Care in the Twin Cities, via e-mail: "Let's be clear. Price means nothing in health care today."

You could also say that price means many different things, as the ear tube example attests. A casual observer of health care prices might conclude that they're random, seemingly made up on the fly. That's not the case, but it might feel so because a procedure, even one offered by the same provider, can bear many price tags. The reasons for this can be traced to the unique nature of health care services and the nation's third-party payer system, where employers and government foot the bill for most medical treatment.

Instead of a straightforward supply-demand transaction between a doctor and an ill patient, the third-party payer system induces a multitude of additional transactions between providers, insurers, employers and consumers. These cumulative transactions dictate who can get (insured) care, where, at what cost, who's responsible for the bill and in what proportion. So different prices are charged to different patients for different reasons. Those without private insurance or government health care have the "luxury" of avoiding this complexity—and are rewarded with prices that can be several times higher than those for the insured patient. It sounds, and is, confusing.

This complex pricing structure is coming under greater scrutiny because medical costs have been rising steadily. As employers pay more to insure workers, some are cutting back on health care benefits, passing on more of the cost to workers or both; some are dropping coverage altogether, leading to more uninsured individuals. As a result, consumers are being both encouraged and coerced to become more savvy health care shoppers.

In response, consumers, employers and others interested in health care costs are demanding greater transparency and simplicity to understand it all. The health care industry has responded with cyber truckloads of information. But as consumers forage through available information, it doesn't take long for the head-scratching to start, because prices aren't really prices—they are charges, costs and payments. Sticker prices are mostly suggestive, and what you pay probably isn't what John or Mary pays.

Achieving a reasonably transparent pricing system for health care services is a torturous task. Moreover, even if done perfectly, transparency doesn't offer a panacea for escalating medical costs. It turns out that when it comes to choosing from the medical menu, prices are less important than our ever-growing appetite for health care.

Still, those grappling with the pricing issue say that transparency should help everyone involved—patient, payer and provider—derive greater value from their health care dollar.

A clear meaning of transparency

Some infer that wide price ranges mean that health care is not transparent and assume that a common service should trend toward a common price among providers.

But markets often offer seemingly similar goods at very different prices—a haircut can cost $10, $100, even $1,000. Where prices vary widely, consumers typically have access to information that helps them determine the value of money spent, and this is where transparency critics have a legitimate bone to pick (more on this later).

Price transparency means that sellers have clear prices attached to services, and buyers understand those prices. Here, there is an additional assumption that health care buyers don't understand the price of health care. That's not likely the case. Employers surely know what they pay for private health insurance for their workers; health insurers negotiate in advance the prices they will pay providers; consumers might have a poor idea of the total cost of a given procedure, but that's somewhat beside the point because they usually aren't paying the whole bill. Consumers tend to be pretty familiar with their out-of-pocket costs for health care, whether for insurance premiums or the co-pays and deductibles embedded in such policies.

But more costs are being passed on to consumers, and consumers are hitting the market more directly as buyers of health care (see article on consumer-driven health plans). These trends make transparency more relevant because most consumers are not familiar with the multifaceted, tiered pricing structure of health care services, making it hard for them to know what prices apply to whom and under what circumstances.

Is that for the arm and the leg?

Price transparency probably wouldn't be on the minds of so many in the first place were it not for persistent and large increases in the cost of health care.

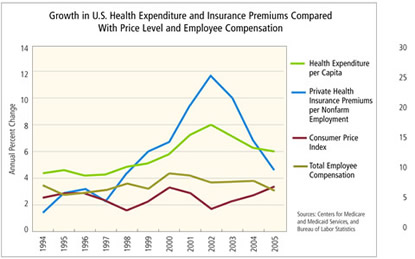

National spending on health care has risen almost 7 percent a year since 2000. That, in turn, has pushed up the cost of private health insurance premiums, which have been trending downward of late but still managed to increase by 8 percent a year since 2000. Both of those health care spending trends are well above the rate of either inflation or worker wages over the same period (see charts).

Rising costs always generate concern, whether they're paid at the doctor's office, the gas pump or the grocery store. In health care, however, cost concerns appear to be reaching an acute chronic-fatigue stage. A 2006 survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute found that "[r]ising health care costs are a primary driver of America's increasing dissatisfaction with the nation's health care system. … Many Americans report that rising health care costs have hurt their household finances and believe that steps should be taken to slow the increases."

A survey conducted this past summer by Consumer Reports National Research Center found that 29 percent of people who had health insurance were underinsured, with coverage so meager they often postponed medical care because of costs.

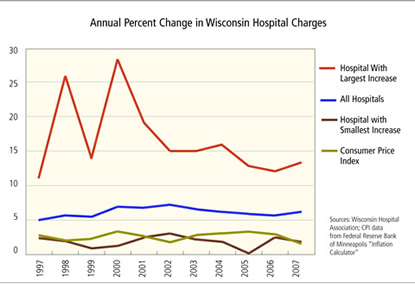

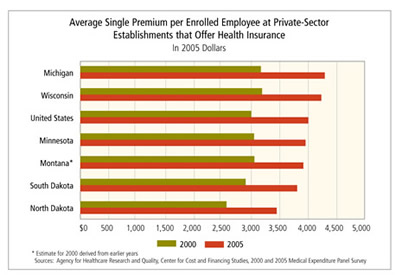

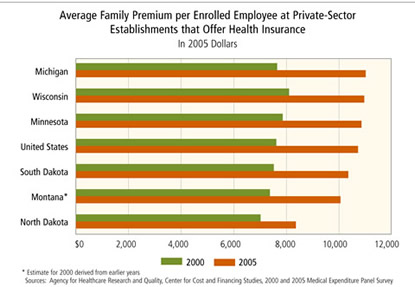

It's not just a people problem, but a business one as well, because employers pay the bulk of private health insurance costs, and premiums have been rising steadily in district states (see charts below). Higher medical costs eat into operating margins and divert attention away from core business issues. A report earlier this fall by the Kaiser Family Foundation noted that 69 percent of firms offered health benefits to employees in 2000. By 2007, it had dropped to 60 percent of firms, "driven largely by a drop in the percentage of small firms that offer coverage."

"Health-care costs have been the No. 1 issue facing small-business owners since 1986," the National Federation of Independent Business says on its Web site, "and those concerns are growing."

Such anxiety has made price transparency a prime topic in health care. President Bush signed the Executive Order on Transparency in August 2006 in Minneapolis, promoting efforts to improve price transparency and quality in federal health care programs. In his formal remarks, Bush said, "Obviously, all of us are concerned about costs. You know, I hear it a lot. … You talk to small-business owners and one of the big concerns they have is the cost of health care. ... It's troubling. It doesn't matter what your political party is; it's an issue that needs to be addressed."

Can you see me now?

As more attention turns to health care pricing, people are finding out that it's a complicated affair, to put it generously.

It wasn't so long ago that the very notion of having health care prices at your fingertips was almost unthinkable. Ask for a price quote over the phone, and you'd likely get the oral equivalent of a blank stare. But thanks to legislative mandates, technology investments, volunteer efforts among private entities and the pressure from restless patients and employers, a comparative flood of information is available online today, at least if you know where to look and what to look for. But there's enough variability among Web tools to confuse or mislead the uninitiated (see sidebar).

So transparency is seeping into the health care system, but pricing remains complicated, thanks in part to all of those separate—and oftentimes confidential—transactions between employers, health plans and providers before a patient ever steps into a doctor's office. But achieving greater simplicity is tough for reasons that go beyond mechanical bean-counting. Many sources argued that health care is inherently more difficult to price than other products and services.

"People would like health care to look like retail. But it's not like buying a tube of toothpaste," said Cindy Morrison, vice president of public policy for Sanford Health, a Sioux Falls, S.D., health organization with more than 150 care facilities in a four-state region. "If my knee hurts, I'm not going to a Web site. I'm going to my doctor. … The consumer is very intimate with their doctor when it comes to their own health."

Giving consumers an accurate quote on care also requires that the provider know something about the patient in advance, according to Deb Fischer-Clemens, director of the Center for Public Policy at Avera, a health system headquartered in Sioux Falls with 229 care facilities in eastern South Dakota and surrounding states. If a person having knee surgery has diabetes, high blood pressure "and six other things wrong with him … the cost is totally different" than for someone with no pre-existing conditions or potential complications, she said. "I think there are so many variables to consider."

Then there's the not-so-minor matter of the underlying quality inherent in a price. To the extent providers have been reluctant to reveal prices, it's often because they see little value in a static price detached from any measure of comparative quality and value of that service; some believe it's even misleading to allow consumers to shop on price alone.

Measuring health care quality requires an assessment of patient sickness and treatment success. A lot of work is being done across the district and nation to better understand what quality care is and what health outcomes it produces under a variety of conditions. But the inroads here are very slow, as are any consumer-friendly ways of connecting quality to price tags.

Indeed, even if you build the perfect price site online, would people come? You can provide consumers with all kinds of information, but that doesn't mean they will use it. So far, at least, online price tools aren't crashing from heavy traffic. The Wisconsin Hospital Association hosts PricePoint, one of the first, and still more sophisticated, pricing tools to come online. Visits to the site are "steady at about 300 per day, with occasional spikes driven by news stories," according to Joe Kachelski, vice president of the WHA Information Center, corresponding via e-mail.

Sanford Health's pricing effort occupies an isolated corner of the organization's Web site. When it was first rolled out in January 2006, "it was news," according to Morrison, and traffic poured into the Web site. But after that initial surge of users, "it fell off dramatically." Currently, the site ranks 70th in terms of the most visited page on the Sanford Web site, Morrison said.

Some of the reasons are cultural. Today, virtually all information is online, which ignores the fact that many elderly people—easily the largest and most expensive group of health care consumers—don't own computers; fewer still are Web savvy.

There are also practical matters to consider. For example, in emergency or end-of-life situations—which often demand very expensive care—consumers or their loved ones are not going to look for quotes from different providers. The emotional timing of health care decisions doesn't always align itself well with a comparison- shopping approach. You can't compare prices until you know what's wrong with you, and that often requires an office visit. Once there is a diagnosis, cost consciousness often takes a back seat to the desire for immediate treatment. If something serious is detected and the doctor wants to order a CT scan, blood work or other tests, a patient is unlikely to go home to find out if that clinic's services are the cheapest in town, delaying tests for days, even weeks.

Belly up to the health care bar

All of this is secondary to the real underlying problem, according to numerous sources—namely, that full transparency is irrelevant to a large majority of health care consumers with health insurance coverage through employers or government health programs like Medicare and Medicaid, because they pay only a small fraction of the total bill, whatever it is.

"Does transparency matter when I'm not paying the bill? I don't think so," Morrison said. "If the company is going to pay 80 to 85 percent of the bill, I'm not going to be engaged."

Brase, from the Citizens' Council on Health Care (CCHC), agreed: "Price transparency means nothing to those who are not paying the bill."

To be sure, consumers today are paying more for health care. Figures from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), for example, show that out-of-pocket expenditures rose by two-thirds from 1995 to 2005, to $250 billion. In Minnesota, the percentage of private-sector employees enrolled in a health plan that had a deductible jumped from 53 percent in 2002 to 73 percent in 2005, according to the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the average deductible for single coverage in that state rose from $412 to $710. Co-pays also rose from $16 to $20 per visit.

But those increases have done nothing to slow health care consumption, and many in the industry say utilization, not transparency, is the real crux of medical cost inflation. For example, hospital outpatient visits per capita doubled from 1985 to 2005, according to the American Hospital Association.

Those visits aren't just for the sniffles, either. According to a 2005 article in Health Affairs, the treatment prevalence for certain diseases—like pulmonary conditions, arthritis, mental disorders, back and upper gastrointestinal problems, diabetes, hyperlipidemia—went up between 50 percent and 100 percent on a per capita basis from 1987 to 2002, while average cost per treatment for some of those conditions actually went down, and several others rose less than the rate of inflation.

"We think a lot of (cost inflation) is utilization. Health care is thought of as a right," said Morrison. "Until you get to the heart of utilization, you won't have massive change."

Janet Silversmith, director of health policy for the Minnesota Medical Association, said by e-mail that about 80 percent of health care dollars are consumed by about 20 percent of the population, many of whom are dealing with chronic conditions, emergencies and end-of-life care. "As such, price transparency, and its ability on its own to reduce health care cost inflation, will likely be limited."

Kachelski said WHA believes that health care demand "is a far more significant factor in rising health care costs than the change in unit prices." Higher use of medical services can be expected as the population ages—older people tend to be more frail and sick, and consume more health care—or when advances in diagnostic and treatment technology become available. But an unknown portion of the increase also "is being driven by patients overly insulated from the true cost of care," he said.

Was blind, now I see

Even if transparency isn't a cure-all, it is part and parcel of a clear consumer movement pushing health care to become more efficient, patient-focused and price conscious.

Many sources acknowledged the difficulty in health care pricing, but stressed that such obstacles shouldn't give providers a free pass on transparency. James Hynes is the executive administrator of the Twin City Pipe Trades Service Association (TCPT), a skilled-trade union representing plumbers, pipefitters, steamfitters and others who work with pipes and fittings. (Hynes is also on the board of directors for the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.)

Hynes agreed that health care pricing is complicated. "It's not all science. Some of it is art," he said. "It's not as clear as choosing between the leather or cloth (seats) in a new car. … It's not as black and white."

The association contracts with major health plans for access to provider networks and their negotiated discounts, among other things. But the association's health plan for members is self-insured and self-administered, meaning that it designs its own health plans and pays all the medical bills, giving Hynes a unique perspective on health care's inner workings.

Hynes said the health care industry underestimates people's ability to shop for health care. "People are smart enough to buy cars, homes, trips and get to this point in their lives … and they are smart enough to buy health care for themselves." For sophisticated products, consumers generally have access to a lot of information to help them understand what they get for their money. "You don't have that for health care," Hynes said.

Certain sectors of health care, like cosmetic surgery, have already opened the window of transparency out of necessity and are doing quite well. The total number of cosmetic surgical procedures—which are not typically covered by insurance, but paid out-of-pocket—rose almost 300 percent from 1992 to 2006, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

Other sources pointed to LASIK eye surgery. The vision-correction procedure has become very popular despite the refusal of insurers to cover it. "Not only have the prices dropped exponentially, there have been advertised prices from day one," said CCHC's Brase.

The emergence of retail clinics (also called "convenient care" clinics) is a trend built around the dual notions of transparency and convenience. Such clinics are typically located at a retail destination—like a discount or grocery store—and staffed by a nurse practitioner or physician. Visits are on a walk-in basis, with wait times of usually 15 minutes or less. A handful of treatments are offered for common illnesses, like throat, ear, sinus and bladder infections. Treatment costs, usually listed prominently on a menu board, typically run between $30 and $100—often half the cost of comparable treatment at a traditional clinic.

The first such clinic opened in a Minneapolis Cub Foods store and led to the MinuteClinic franchise, still located in Minneapolis, which now boasts 200 clinics in 20 states. There are believed to be two to three dozen convenient care firms nationwide, and various sources put the total number of clinics between 400 and 1,500 by year's end. It's estimated that about 7 percent of Americans have visited a convenient care location, according to the Convenient Care Association, the industry's lobbying group. Many patients pay cash, but most clinics accept insurance, and insurers are warming to the model.

Hynes said the TCPT was the first health plan to reimburse MinuteClinic for the procedures performed at such clinics. The decision was an easy one, Hynes said, because his members were tallying more than 5,000 visits to doctors' offices for the same procedures offered at MinuteClinics and at prices that were much higher. TCPT gave clinics full reimbursement, and members faced no co-pays or deductibles to use these clinics. "Members really like it, and it saved money. Those two things don't happen often," Hynes said. His only complaint was that "not as many are using it as I would like."

Don't know what we don't know

Though there is widespread dissatisfaction with various facets of the U.S. health care system, the system can't be changed without a better idea of how existing resources are spent and to what end. And for that, "transparency is one additional way to bring focus to the discussion," said Arnold "Chip" Thomas, president of the North Dakota Healthcare Association.

Kachelski, from the WHA, pointed out that there is still a lot to learn about, and from, transparency. "Health care transparency is in its infancy. There's no doubt that what's available now will be very different than what's available in the future," he said. "But those changes will be driven by better understanding of market needs and a growing number of patients for whom actual prices matter."

As more price information spills into the marketplace, more players are coming on the scene to make it more useful. MedCare Compare, for example, is a Minneapolis-based firm hoping to become a private online clearinghouse of price data. Terry Hauer, vice president of marketing and sales, and two other owners have been working for two years to "create a true marketplace" where consumers and providers can meet as "willing buyers and willing sellers, which health care has been mostly void of."

Any provider can add price information to the MedCare site free of charge. MedCare then sells access to this price data to employers in the hope that they will encourage employees to become better, more cost-conscious consumers, which will save money for both employers and employees down the road.

Hauer acknowledged that the site currently does not have a huge percentage of either providers or available procedures. And not everyone is as enthusiastic about the model as Hauer. Larger providers that have more leverage in contract negotiations with health plans and other patient populations "have not been as excited" about this open-market type of Web site as Hauer had hoped. Small to medium-size providers, on the other hand, "have been ecstatic" to have the opportunity to openly compete for patients based on price, he said.

"Some providers see this as a race to the bottom because it's all about price. And that's not the case. It's about finding your niche" in health care, Hauer said. He likened the matter to coffee, where some people are willing to shell out $5 for a fancy Starbucks drink and "others will throw down 50 cents" for a cup of joe at a gas station. "People will make those decisions (on quality and price). Not all (providers) are going to be Wal-Mart."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.