In the debate over the direction of middle class lifestyles, there is a scene oddly similar to one in the “Wizard of Oz”: Pay no attention to all those things going on behind the garage door.

Money doesn't buy happiness, as the cliché tells us. In the vein of this research on middle class progress, rising income is not the be-all and end-all for a contented life. But rising income is the gatekeeper to a higher standard of living that most people seek—indeed, have come to expect—over the generations and the course of their lifetime.

No matter how you crunch the data, there are examples of lackluster income growth for some kinds of households and in certain locations—stagnation that can’t be calculated away. And many are getting the double whammy today with the onset of much higher expenses for necessities such as gasoline and food, provoking complaints that the middle class standard of living is going in the tank.

No matter how you crunch the data, there are examples of lackluster income growth for some kinds of households and in certain locations—stagnation that can’t be calculated away. And many are getting the double whammy today with the onset of much higher expenses for necessities such as gasoline and food, provoking complaints that the middle class standard of living is going in the tank.

But a long-term generational assessment of middle class progress has to look at the majority of the population over time, because there are always exceptions to long-term trends, and periods of slow growth tend to be balanced by periods of rapid growth. Throughout U.S. history, the middle class has had to persevere through periods of economic stress, and today is no different.

So in the big picture, is the middle class better off today than the previous generation? Given the many caveats to income and wage growth trends since 1979 (see cover article), it helps to take a look at how people actually live for additional clues. A look at the middle class through the lens of consumption shows that it enjoys considerably more creature comforts than previous generations.

They don’t call it a castle for nothing

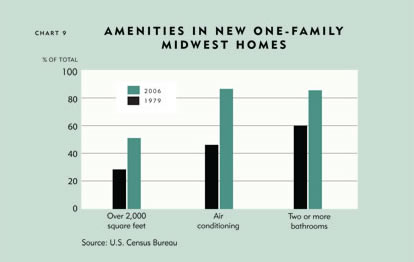

Few assets demonstrate an improving standard of living better than people’s homes, which are unequivocally larger and have more amenities than in the past. In 1979 the median size of new single-family houses in the Midwest was 1,605 square feet, according to U.S. Census data. By 2007 median size had grown 29 percent to 2,064 square feet. Nationwide, new homes grew 40 percent in size to 2,277 square feet. Many more homes today have air conditioning as a standard feature, and they boast more bathrooms (see Chart 9).

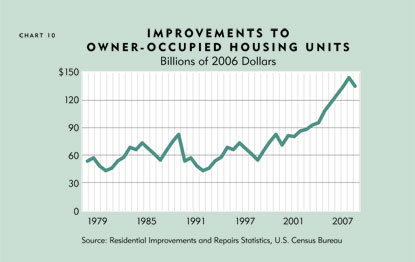

But that’s brand-new housing, you might say, and not everyone in the middle class can afford what’s getting built today. OK, but for those living in an older home, there is a good chance they've spent some money adding on an extra room or remodeling a bathroom or kitchen. Between 1979 and 2006, annual spending on improvements to existing, owner-occupied housing increased 167 percent (inflation-adjusted) to $144 billion, according to residential improvements and repairs statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau (see Chart 10).

I want, therefore I am

It’s also useful to peer into people’s homes to see what possessions they have and how they live.

Like past generations, people have accumulated more stuff over time, evident in the number and size of garages—the prevalence of three-stall garages in new Midwestern homes rose from 18 percent in 1993 to 32 percent in 2007—and the rapid expansion of the mini- and self-storage sector, which was virtually nonexistent in the 1970s and is now a staple in communities large and small.

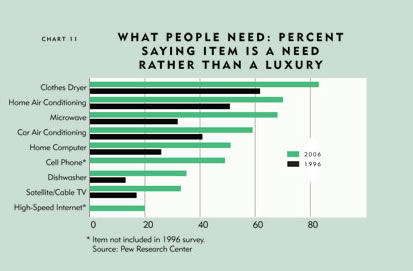

Today, more homes are likely to sport amenities that were seen as luxuries a few short decades ago. According to the most recent iteration of an annual survey by the Pew Research Center, only 32 percent of respondents said the microwave oven was a necessity in 1996; 10 years later, 68 percent of respondents said they couldn't get by without one. In 1996, cell phones were not even part of the survey; in 2006, almost half said they were a necessity (see Chart 11).

For regular items on surveys going back to 1973—like clothes dryers, dishwashers and air conditioners—“this march toward necessity has tended to accelerate in the past 10 years,” the Pew report noted, adding that income has a direct effect on whether a person views goods and gadgets as necessities rather than luxuries. The old adage proclaims that necessity is the mother of invention. These findings serve as a reminder that the opposite is also true: invention is the mother of necessity.”

Some of this demand stems from the fact that many new electronic devices and household conveniences—cell phones, televisions, microwaves, computers—have become cheaper over time. Regardless, it means that more households can afford items once seen as luxuries.

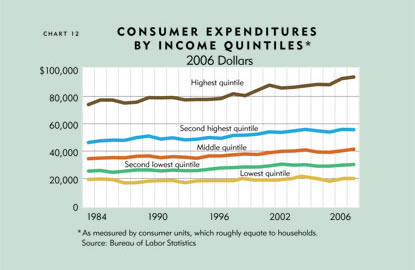

The Consumer Expenditure Survey, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, has collected detailed data on consumer spending going back to 1984. As you might expect, growth in consumer expenditures was strongest at the top, following income gains. But spending by the middle income quintile (and the middle three quintiles, in fact) rose significantly as well

(see Chart 12).

The CES also gives a conservative estimate of consumer spending, particularly over time; it’s well established that consumption growth as measured by the CES is much smaller—and likely less accurate—than personal consumption expenditures tallied by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, based on national income and product accounts, which are used to calculate gross domestic product, among many things. The disadvantage of BEA figures is that expenditures are not broken down by income.

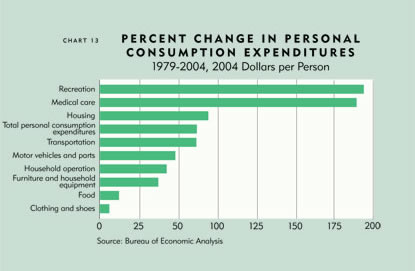

So what are people spending their money on? BEA figures show steep increases in expenditures for housing and health care from 1979 to 2004 (the most recent categorical figures available; see Chart 13). Though costs for both have been increasing faster than inflation, consumption is also higher for each—bigger houses with more amenities and more visits to more health care practitioners, be they family doctors, specialists, therapists or dentists.

It’s true that the rising cost of health care has pushed it out of reach for some: Nationally, health care coverage has sagged slightly, the number of uninsured has been rising, and workers and their families are paying more for that coverage. However, it’s also true that employer costs have gone up even faster, and workers’ share of health care premiums has actually dropped since the mid-1990s, according to the Employment Benefits Research Institute.

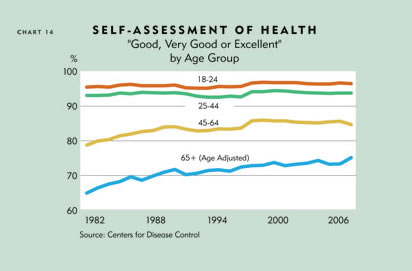

Still, many people might feel that they’re spending more for the same generic health care product. But the data suggest that the care received is leading to better health—not everywhere and in all ways, but overall. These net gains are translating into longer life: Since 1979, life expectancy for males is up five years to more than 75 years. Life expectancy for women has increased less (about two and half years), but exceeds 80 years. That’s probably not all due to health care spending, but neither is it likely a coincidence or statistical anomaly: Older people are increasingly saying they are in better health (see Chart 14).

At the other end of the age scale, infant mortality rates have been halved since 1979, dropping from 13.1 to 6.6 per 1,000 births. The effect is hard to overstate. Since 1980, about 4 million people have been born in the United States each year. The reduction in the infant death rate means that every year, 26,000 more infants get a chance at life today than would have without such improvement. For middle-class families, lower infant mortality goes to the heart of improving quality of life.

But paychecks are not just going toward health care and houses. People are also having more fun with their money: Entertainment spending has increased more than any other category. Increased entertainment spending is possible in part because of lower inflation-adjusted expenditures for things like food and clothes. That trend is likely to shift in the opposite direction due to recent higher prices for food, gas and other energy. But at the same time, a declining housing market will likely lower (or at least moderate) annual living expenses, and the past several years have witnessed unprecedented discounts on cars and trucks.

I’m fine, you’re not

Living standards are a squishy concept, because money alone doesn’t dictate how comfortable one feels. A household earning $90,000 in rural North Dakota or Montana will likely feel richer than a household bringing home the same figure in the Minneapolis suburbs.

Nor are all expenditures a net benefit to a household in terms of quality of life. As more parents work, daycare expenses often become a large and unavoidable expense with murky net benefits. In other cases, possessions and attainments that have come to define middle class living are simply more difficult to afford. The cost of a college education, for example, has spiraled well beyond the rate of inflation and rising wages (combined, in fact), and many worry about what that means for their children’s future. And when common middle class goals—like paying for college out of your own pocket—seem out of reach, it’s enough to make people question social progress; never mind the fact that a significantly higher percentage of people go to college today than 30 years ago.

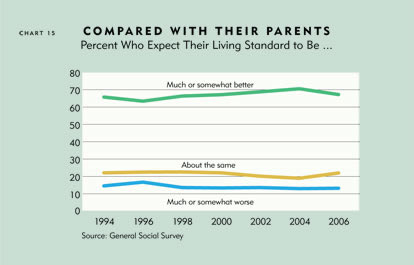

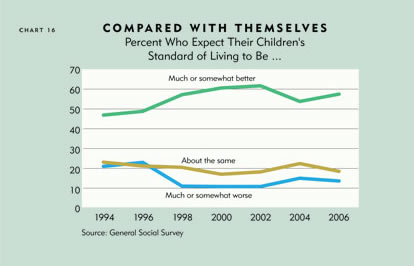

People’s opinions of middle class progress also depend on whether they’re looking at a mirror or through a window. They tend to be pessimistic about broad social trends, but are nonetheless optimistic about their own situation, as well as their kids’ future, according to the most recent iteration of the General Social Survey, one of the longest-running surveys in the country, which began asking about comparative standards of living in the mid-1990s (see Charts 15 and 16).

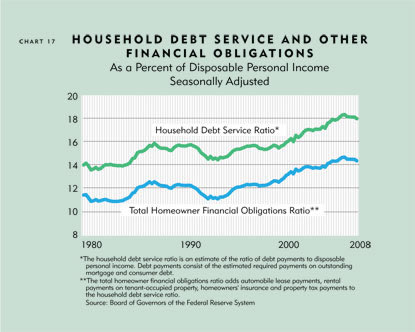

Whether or not accelerating consumerism and material wealth make Americans better off is itself controversial. More households have more debt today than ever before, particularly mortgages and other home-secured debt. Household debt service and financial obligations as percentages of disposable personal income have been steadily rising (see Chart 17). While net household assets and wealth have increased similarly, the current housing foreclosure crisis offers plenty of anecdotes regarding the dangers of mounting household debt.

But neither is higher debt a universal problem. People have always borrowed against future income, and the more people earn, the more likely they are to use—and can afford—such financial leverage to enhance their standard of living.

Historically, society has gauged progress by the growth in “things obtained”—whether it be housing, health care, education, entertainment or sundry consumer goods and services—because people tend to purchase things that make life more convenient, pleasurable and productive. And virtually across the board, the middle class is consuming more of everything, which makes the notion of a stagnant middle class an argument that doesn’t fit well in the garage.

Related articles: Say hello to the modest good life for me

Just what is the middle class and other stuff

Has Middle America Stagnated?, The Region, September 2007

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.