Video: fedgazette Editor Ron Wirtz on manufacturing

The Quick Take: Manufacturing has been a bright spot in an otherwise sluggish economic recovery. After being pummeled by the recession, output growth returned to manufacturing in 2009, and employment gains followed a year later and have continued. Gains have been seen across district states, largely in durable goods manufacturing. Sources of that growth include inventory restocking after steep recession cutbacks, growing exports, and strong energy and agricultural markets. There is even anecdotal evidence that some production is being “reshored” from other countries. The recession itself can take some backhanded credit for forcing companies to reevaluate and improve their products, processes and personnel.

Many hope the sector’s rebound will return the industry to its historical prominence in the national economy. That’s unlikely. Despite strong output growth, manufacturing employment has risen only modestly and is still far from prerecession levels. But that’s actually good news for the sector: Rising output coupled with modest job gains is an indication of high productivity, a key to manufacturers’ future competitiveness.

On a sunny day in May of last year, workers at OEM Fabricators, a heavy-industry fabrication shop in Woodville, Wis., did not come dressed in the work clothes they normally wear to weld, machine, paint and assemble products for customers. Instead, they came in suits and ties to pay distant respects to the deceased.

Despite coming off a strong year of growth, the company was hosting a funeral. Even the community showed up. Workers dug a hole and laid a wooden coffin to rest right there on company grounds. And then they celebrated, ate and danced to a Dixieland band. For they had all shown up to bury the recession—literally, it was inscribed on the coffin—that was long past for the company, but still lingering on the minds of many.

OEM President Mark Tyler said the faux funeral was meant to change people’s mindset. Times were tough during the recession. “It dropped a piano on our head” in terms of sales, and employment was more than halved to about 150 workers, Tyler said. The company’s fortunes soon turned around, but you wouldn’t have known or felt it around the company.

“You know the guy in [the comic strip] Li’l Abner that always had the black cloud over his head? Well that’s what it felt like for a long time, even within the company. We were growing; we were coming out of the [downturn]. And yet there was this feeling that things were bad,” said Tyler. “But things weren’t bad. Things were good—we’re riding this rocket ship in terms of revenue growth, and earnings are strong. And so we thought, ‘How do we break this attitude? And we said, ‘Let’s bury it,’ and thought a New Orleans-style funeral might be appropriate.”

OEM hasn’t looked back on the dark days. Last year, revenues grew 75 percent and are on a similar pace this year, Tyler said. The company expanded its Woodville site, and it expects to move into its biggest facility yet in neighboring Baldwin. The company’s current workforce of 500 is 50 percent larger than its prerecession peak.

OEM Fabricators is a heavy-industry fabrication shop in Woodville, Wis., that serves the robust energy and agricultural markets, and other customers of machinery and durable goods.

Not all manufacturers are experiencing the same success as OEM, but the sector in general has been a bright spot in an otherwise sluggish recovery. Output has recovered, and many firms are seeing revenues, particularly sales of durable goods, return to and often exceed prerecession levels. Even manufacturing employment has risen in district states, reversing many years of decline.

Many factors are involved, including a bounce-back in orders stemming from steep inventory cutbacks during the recession, strong exports and some evidence that more orders are being filled in the United States rather than elsewhere—all of it facilitated by a seemingly manic focus on productivity and adding value to products, courtesy of the recession. Firms that managed to hang on through the recession have been forged stronger by the need to reevaluate products, processes and personnel from top to bottom. The experience made companies leaner and more efficient, and their products more competitive.

Many hope for a manufacturing renaissance that might return the industry to its former prominence in the national economy—creating jobs, vacuuming up unemployed workers and making “Made in the USA” more than an economic wish or election slogan. Manufacturing output is doing its part, rebounding past prerecession levels. But manufacturing employment—while growing of late—is still far below prerecession levels, and the long-term job trend since the 1970s is decidedly downward.

But maybe counterintuitively, given the public’s preoccupation with job growth, the dual trend of rising output and modest job growth is itself a positive development for manufacturing because it signals rising productivity, a key to long-term health and survival for firms and their workers.

Recession: R.I.P.

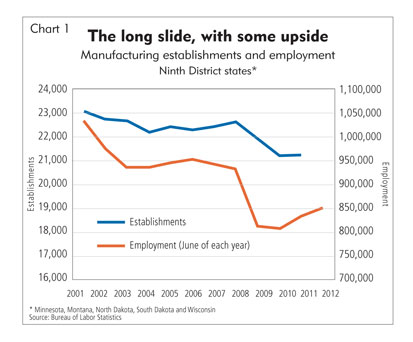

The manufacturing industry had a forgettable past decade, thanks mostly to bookend recessions. After mostly treading water in the middle of the decade, manufacturing establishments and related employment in the Ninth District were pummeled by the Great Recession of 2007. District states lost more than 1,300 (net) manufacturing firms, countless others saw cutbacks and 150,000 manufacturing jobs were eliminated (see Chart 1).

But things started turning around for many manufacturers by about the middle of 2009, when the recession officially ended. Some, even much, of the early rebound was simply rebuilding inventories, which fell dramatically during the recession as businesses across the economy cut orders in light of the financial crisis and simply used what they had on hand. Manufacturers responded in kind; shipments sank during the recession, then steadily rebounded.

Daniel Berdass is president of Bermo Inc., a manufacturer of metal components in Circle Pines, Minn. During the last recession, “we dropped tremendously,” he said, and employment shrunk by about half. But business started rebounding within two years, “and it’s been a snowball ever since.”

Bermo sales since the recession’s nadir are up 300 percent—from the “teens to the sixties [million],” according to Berdass—and are now above prerecession levels. Employment has grown on par with revenues as well, he said, and the company now employs over 200 people at its 286,000-square-foot headquarters facility.

Similar stories of transition, rebound and growth are easy to find around the Ninth District. Bus maker Motor Coach Industries is adding about 80 jobs in Pembina, N.D., a community of just 600 on the Canadian border. In the Twin Cities, steel-maker Gerdau is investing $50 million to significantly increase capacity at its St. Paul plant. Just to the east, Polaris Industries, a maker of all-terrain and other recreational vehicles, is adding 89 jobs at a 140-worker plant in Osceola, Wis., a partial reprieve from its 2010 announcement that it would close the plant entirely and eliminate more than 500 jobs. In Sioux Falls, S.D., Twin City Fan & Blower is building a new 50,000-square-foot facility and expects to hire more than 50 employees.

Not everyone’s a winner in the sector’s recovery, of course. Agribusiness giant ADM closed its ethanol plant in Walhalla, N.D., this summer, eliminating 61 jobs. In Sartell, Minn., a Verso Paper plant that employed 259 workers was destroyed by fire in May and will not be rebuilt given high operating costs and sluggish paper markets. At the end of last year, Ford Motor Co. closed its 86-year-old truck facility in St. Paul, putting 800 people out of work. At its zenith in the 1970s, the plant employed more than 2,000.

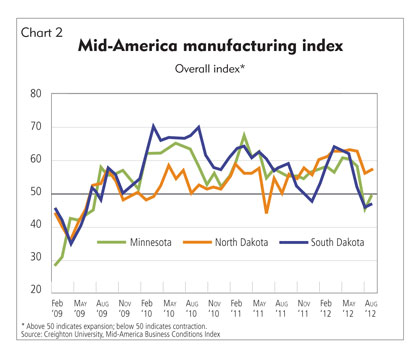

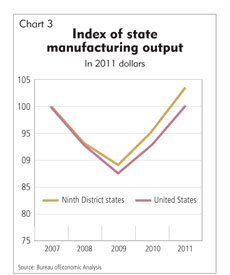

Though some manufacturing indicators softened over the summer, most macro measures suggest that the industry needle has moved to the positive side overall. For example, the number of manufacturing job vacancies has been on the steady uptick, from fewer than 2,000 in the fourth quarter of 2009 to 4,900 two years later, according to surveys by the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED). The Mid-America Manufacturing Index, which regularly surveys producers in Minnesota and the Dakotas, has indicated expansion among district manufacturers since the summer of 2009. (See Chart 2; this summer, however, producers started reporting some softness. More on current conditions later in the article.) That optimism was validated by steep increases in manufacturing output in district states since 2009, which outpaced the sector’s recovery nationwide, according to the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis (see Chart 3).

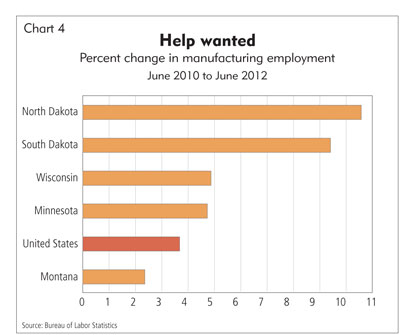

Strong optimism and output have led to recent hiring—a notable reversal for the sector—starting in 2010 (see Chart 1). From June of that year to June 2012, manufacturing employment grew by 5 percent among all district states, or about 41,000 jobs. Though the manufacturing base in the Dakotas is still quite small—fewer than 70,000 jobs combined—the two states saw sector employment expand by nearly twice the district rate (see Chart 4).

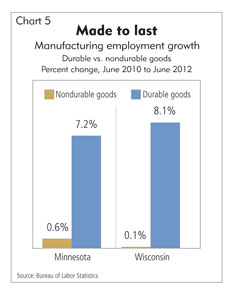

But not all manufacturing jobs are created equal, and statewide data obscure a large amount of industrial variation. For example, employment has grown significantly faster among makers of durable goods—things like machinery, transportation equipment, metal fabrication—compared with nondurable goods (see Chart 5).

Even within durable goods, some sectors have not recovered. In 2005, wood products employed 52,000 workers across district states, many of them making lumber and other products for the housing industry. The subsequent housing bust sawed off about 40 percent of jobs—some 20,000—by 2010. Since then, employment levels have been merely flat. Responding to a fedgazette online survey, the owner of a western Montana lumber company said it has had to cut payroll significantly, adding that any “sunny spot” in manufacturing seen elsewhere “doesn’t exist here. … I honestly don’t believe we’ve hit bottom. Public confidence in our area is as bad as I have seen it in 37 years.”

Energy and ag

For those industries seeing growth, there are many sources, but a few seem to stand out. Robust energy and agricultural sectors are big consumers of machinery and other durable goods, and manufacturers serving these markets have seen little downside in recent years, according to Andy Peterson, head of the North Dakota Chamber of Commerce. “Those two sectors have been blown out of the water, and companies can’t keep up.”

With strong crop prices for several years running, farmers are taking the opportunity to invest in their operations. That translates into more tractors and other farm equipment purchased from the likes of Bobcat, a Bismarck, N.D., maker of compact loaders, excavators and other farm equipment. The firm announced in April that it was expanding and adding about 200 jobs in partnership with Menlo Worldwide Logistics.

International companies are also looking to bring products closer to their final markets. Last month, German-based Geringhoff announced plans to invest over $20 million in a new plant in St. Cloud, Minn.—its first manufacturing facility in the United States, which will make corn-harvesting and other farm machinery. The move will create 100 jobs initially, with significantly more anticipated in the future.

A strong ag sector also trickles to niche markets like drainage tile for farmland. In February of last year, Willmar, Minn.-based Prinsco opened a tile production facility in Beresford, S.D., and broke ground on a second district facility this year in Fargo, N.D. But that’s only the half of it. Advanced Drainage Systems also opened a production facility in Buxton, N.D., in early 2011 and this summer announced plans for a new multimillion-dollar facility in Watertown, S.D.

The nationwide oil and gas boom, including intensive drilling of the Bakken oil shale formation in western North Dakota and eastern Montana, has been another obvious source of demand for manufacturers. Mark Oelke owns M & W Machine, a small machining interest in Three Forks, Mont. Via email, Oelke said 2008 and 2009 “were rough years. … I came real close to laying off a very seasoned employee.”

So in 2011, “as a means of survival,” Oelke started traveling to the Bakken, about 400 miles away. It worked. Oelke found business for its boring, milling, welding and other machines, and the company also bought two computer numerical control machines “to cater to what some of the companies were asking for.” That year, business grew by 30 percent and has leapt by 150 percent so far this year—90 percent of which was oil-patch-related—allowing M & W to add three employees. Now, he said, “There’s no downturn in sight.”

Last year, revenues at OEM Fabricators grew 75 percent and are on a similar pace this year. The company’s current workforce is 50 percent larger than its prerecession peak.

OEM Fabricators—remember the funeral in western Wisconsin?—derives more than 40 percent of its current business from oil- and gas-related products, including items like large engine manifolds, stator frames for motors and generators, mixing tanks and myriad other mechanical components. The company has a history of serving others in the energy sector. But as companies have become active in the Bakken, “we have seen increased activity from nearly all of them. … It’s just been an accelerator,” said Tyler, company president.

Prospects also look good for steady business going forward, according to Tyler. “We have been watching the energy sector outlook and have gotten the sense that we are in a level of activity that is sustainable for many years.”

Forged by fire

Many other factors have helped the manufacturing sector. Exports, for example, have grown at exceptional rates since the recession (see Exporting growth). Employer costs also haven’t risen much—workers’ wages have been held in check by the downward pressure of widespread unemployment. From 2007 to 2011, unadjusted average weekly manufacturing wages in district states rose between 7 percent (Montana) and 12 percent (North Dakota)—barely ahead of the rate of inflation only because inflation has been so low.

But in the most fundamental sense, the recession appears to have played an important, if unwelcome, role in the manufacturing rebound. Industry sources widely described the recession as a meet-your-maker event that put everything under the microscope. Those that survived can’t help but be leaner, more strategic and more productive for the experience.

“In this recession, very few companies didn’t get forced to think about their personnel,” said Bob Kill, CEO and president of Enterprise Minnesota, a state-chartered organization affiliated with the Department of Commerce that offers fee-based consulting services to manufacturing firms. But in this recession, he added, “more than in the previous two [recessions], companies have really had to invest.” And it’s not all capital investment. Increasingly, companies are investing in analytics—that’s where Enterprise Minnesota comes in—to see how processes can be more streamlined and efficient to cut labor, energy and other costs.

“Sometimes when you invest, you don’t spend money,” Kill said. “It means sometimes not investing in any new equipment, but improving production processes” or finding other efficiencies that get passed on to customers. As a result, “firms were better able to weather the storm. … What we have left are firms that can compete.”

At OEM Fabricators, “there is no doubt that the recession drove improvements in our operations,” said Tyler. The company looked at personnel and processes, and “many changes were made, leaning our operations.” Employment was slashed during the recession, and while it bounced back fairly quickly, it was done carefully “to retain the efficiencies gained during the recession,” he said. The company also hired some “outstanding, highly skilled” employees who were available as a result of the downturn.

As business increased coming out of the recession, the company also invested heavily in new equipment and technology, which Tyler said “drove even higher levels of productivity.” While OEM employment is 50 percent higher than before the recession, sales have more than doubled. The company is in the process of expanding to an 80,000-square-foot facility in Baldwin, Wis., its third and largest plant.

It’s the same story at Nicolet Plastics, a plastics injection molding company located in Mountain in the northeastern part of Wisconsin. President and CEO Bob MacIntosh said the company downsized its workforce by more than 20 percent in 2009. As business rebounded, “we were able to manage most of the growth with the remaining workforce and some added automation.” The company is doing about $2 million more in business—now at about $10 million—than it did in 2008, “and we still have not gotten back to the ’08 employment levels.”

Many sources also talked about “going up the value chain” to develop products whose competitive advantage is based on more than just low price. That’s the case even for seemingly mundane items like packaging and product containers. Thirty years ago, the container industry “was a brown box to get something to the end user,” said Jim Haglund, owner of Central Container of Minneapolis, which employs about 150 people throughout its 175,000 square feet of plant and generates about $30 million annually in revenue.

The container industry has evolved. Haglund said the company made a big commitment during the last decade to go “lean and green,” hiring the design and engineering talent to go after new, value-added product markets like medical supplies. This brought some growing pains. To package medical products, Haglund said, “it seems like we go through the same ropes as the stent you put in your body.” These companies, he added, “are very strenuous and demanding. But it forced us to get good in quality.”

Striving for quality brought the security of better margins. Haglund said that for a $5,000 medical device, “it’s not a big deal if the packaging is 50 cents more than a competitor. It is a big deal if the product is [worth] two dollars.”

During the recession, Central Container’s revenues dropped about 15 percent. Slowly, they rebounded. Last year was “not bad,” Haglund said, and this year the company’s revenues are up 10 percent, moving it above prerecession levels. “I’m pretty positive,” he said, evident in the fact that the company expected to add 13 workers by year’s end.

Central Container of Minneapolis employs about 150 people throughout its 175,000 square feet of plant and generates about $30 million annually in revenue.

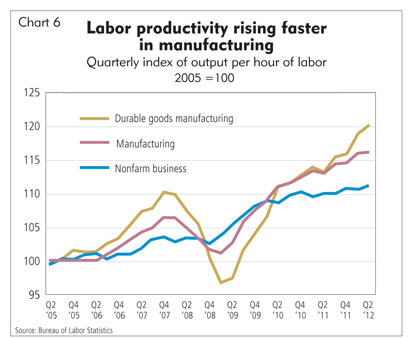

These anecdotes give life to the macro data, which show that productivity is rising among manufacturing firms—and particularly among those producing durable goods. Productivity has also been rising faster in manufacturing than in all other nonfarm businesses (see Chart 6). (There is, however, some debate about how to measure manufacturing productivity. See interview with Susan Houseman, a labor economist with the W.E. Upjohn Institute.)

Big challenges remain

But none of this is to suggest that district manufacturers have found refuge from the tempest of global competition. Challenges are omnipresent, from Chinese competition to the need to constantly innovate to satisfy finicky, fickle buyers.

Kill, from Enterprise Minnesota, said the optimism of manufacturing CEOs is “tinged with caution.” The European debt crisis, America’s own debt problem, a slow national economy, health care reform and other economic concerns “get in the minds of people, and they get more conservative,” said Kill, adding that order backlogs “are good, but future visibility is still very short range.”

This summer various manufacturing indicators were starting to soften. The Institute for Supply Management’s factory index saw three consecutive months below 50 (the benchmark for industry expansion). The Mid-America Manufacturing Index, a regional subset of the Institute’s survey, also dipped into negative territory (see Chart 2).

If that weren’t enough, firms fortunate enough to be doing good business are having difficulty finding qualified workers. A fedgazette survey of Montana manufacturers found that revenue increased over the past two years for half of the 55 respondents (one quarter had flat revenue and another quarter saw revenue decline). But two of three respondents said finding the necessary labor was difficult. In the past year, employers have expressed similar sentiment in surveys by the DEED and Enterprise Minnesota.

Skilled labor conditions are even tighter in North Dakota, which has the envious challenge of dealing with an oil boom and virtually uninterrupted economic growth over the past decade. Peterson, from the state chamber of commerce, said that an executive at Case New Holland told him: “Give me 50 trained welders, and I’ll hire them today. Give me 50 more, and I’ll hire them tomorrow. Give me 50 more, and I’ll hire them the day after.” Those stories abound in North Dakota. He noted that two other large manufacturers in the state had all the business they could handle, “and they can’t get enough workers. … Their greatest fear is not finding enough workers to grow in North Dakota.”

Randy Schwartz, director and CEO of the nonprofit Dakota Manufacturing Extension Partnership, pointed out that North Dakota manufacturers are looking for workers whose skill sets are similar to those working in the oil and gas industry, where wages “are roughly double what they are in many manufacturing companies.” With such hot competition for skilled labor, Schwartz said, “more manufacturers are going to have to avoid becoming the workforce feedstock for the energy industry.”

Is this different?

Despite these myriad challenges, many are cautiously optimistic about the future of manufacturing. Some are gaining confidence from an increasing number of anecdotes about manufacturers “reshoring” jobs back home, or giving contract work to domestic suppliers rather than sending the work abroad (see Made (again?) in the USA).

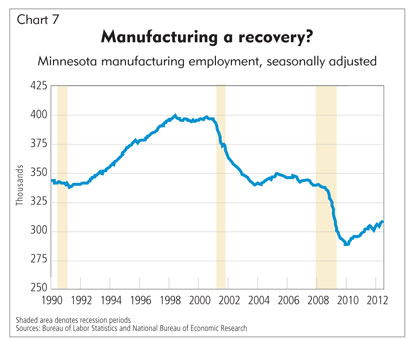

The encouraging thing about this manufacturing recovery is that sector employment has rebounded more quickly this time compared with the 2001 recession (see Chart 7) and to date is roughly in line with the recovery after the 1991 recession, which was subsequently followed by strong manufacturing growth for most of that decade. The Mid-America survey and others also continue to be upbeat regarding future employment.

That’s good news for workers and policymakers fretting about continued high unemployment. But job gains in the sector will probably be comparatively modest; despite 41,000 new manufacturing jobs in district states since the upturn, the industry employs 100,000 fewer workers than it did before the recession, while output in most district states has generally equaled or surpassed prerecession levels.

There is little reason to believe manufacturing will significantly reverse the sector’s steadily sliding share of employment—from 25 percent 40 years ago to 10 percent—because manufacturing today simply requires less labor than it once did, thanks to new technology and rising worker skills. New manufacturing jobs often demand a range of mechanical and computer skills to run sophisticated machines that do most of the production work. “Mechatronics” has become something of a buzzword in some manufacturing circles. It represents a skill set—as well as a curriculum in some district technical colleges—that combines mechanics, electronics, software and other technology, according to Kill. It transitions the manufacturing worker from brawn to brains, but requires fewer workers to produce the same number of widgets.

Kill acknowledged the trade-offs. “Does it require as many employees? No. Is it skilled? Absolutely. Does it pay more? Absolutely,” said Kill. “This is where [manufacturing] is going.”

So while manufacturing in the Ninth District has made a solid recovery by many measures, there is just as much work ahead if manufacturers hope to remain competitive. As Central Container’s Haglund put it, “Status quo used to be status quo. Now status quo is regression.”

For a final tale of both promise and peril in manufacturing, gather around Daniel Berdass, from Bermo Inc., who is something of a celebrity within the industry. “Everyone wants to hear my horror stories. It makes them feel good,” said Berdass.

While Bermo is currently seeing strong growth in its metal components business, it’s been a volatile arc. It went through gut-wrenching upheaval in the last two recessions. In 2001, the company was an international supplier to computer and electronics firms like Dell during the high-flying 1990s. The collapse of the Internet and telecomm bubble with the 2001 recession saw the “loss of 90 percent of our business in 45 days.” The company shut down six plants abroad, leaving only its Twin Cities facility, and employment shrank from 1,200 to just 110. That period “was probably the most difficult thing I ever experienced. You wouldn’t believe the trauma,” Berdass said.

So the company decided that the only feasible, yet risky, move was to shift into heavy equipment prototyping, fabricating and stamping. The thinking, according to Berdass, was that “the bigger and the heavier, the better a chance [production] has to stay” in the United States at which point the company could expect to compete for business.

Berdass said that retrenchment finally took hold after about five years, just in time for a smackdown by the 2007 recession. Revenues dropped and employment got cut in half. But while the firm struggled, “we were used to this. We knew how to shrink.” Recovery took a couple of years, but today “things look very good, very strong,” said Berdass. Even among his competitors, “95 percent of us are doing very well.”

But none of the recent success is much comfort to Berdass because he knows how fast things can change. “It’s very scary. Certainly the next six months look strong … but we’re very cautious.”

Whether the current upturn in manufacturing is merely a temporary sunny spot or something more long lasting is “a question I ask myself every day, and I have no idea,” said Berdass. “You get whacked twice in eight years, it’s very hard. I’m scared. From here it looks strong. But we could get [contracts] canceled tomorrow and things will look terrible. It’s happened before.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.