Video: fedgazette Editor Ron Wirtz on rental housing

The Quick Take: Over the past decade, residential rental markets have seen big swings in vacancy rates and building activity, coinciding with the housing boom, subsequent recession and sluggish recovery. As recently as 2010, vacancy rates were high across much of the nation and Ninth District. But the sector is now experiencing something of a rental renaissance, thanks to strong demand and a dearth of new units, the latter a result of a near shutdown in new construction since the recession.

These factors have pushed vacancy rates lower across the Ninth District, and the outlook for property owners is very positive. New construction in multifamily units is starting to swing upward, but not likely fast enough to overwhelm low vacancy rates. After years of mostly flat rents, prices have started to rise and are expected to continue. Renters, especially low-income households, face something of a scavenger hunt given low vacancy rates. How long these conditions last will depend on the market’s response to tight conditions and on whether the growing share of renting households is temporary or a more permanent equilibrium stemming from the housing market collapse.

As the saying goes, the housing market has been down so long, people have forgotten what up looks like. Sure, there’ve been a few signs of life, but you’ve seen false starts before.

Make no mistake, however, it’s there—the good news about housing—if you just look for it. By all accounts, this is the real thing. This market has strong prospects going forward, and it’s the whole works—rising demand, swinging hammers, new units and rising prices.

But it’s not where you think. It’s past all the for-sale signs and behind all the foreclosures. What’s that? You say the only thing going on in your neighborhood is new rental units and some rental conversions of single-family homes?

Welcome to the robust part of the housing market. While the single-family homeownership market continues to struggle—dominating attention along the way—rental housing markets appear poised to enjoy a few good years, owing to strong sector fundamentals.

But rental markets didn’t get to this point in easy, stair-step fashion. Over the past decade, the industry has generally followed the volatile path of the broader economy, experiencing big swings in vacancy rates and building activity as a consequence of a housing boom sandwiched between two recessions, as well as a sluggish recovery to the later and more devastating recession. This volatility and a household preference for homeownership during most of this period gave landlords little traction to raise rents. As recently as 2010, vacancy rates were high across much of the nation and the Ninth District.

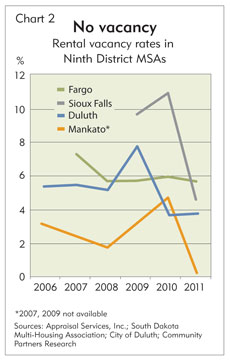

But there has been something of a rental renaissance in the past year or two thanks to pent-up demand and tight supply. Cities across the district are playing the vacancy version of the limbo, besting each other by going lower than others. In Fargo, N.D., vacancy rates are about 5.5 percent; in Duluth, 3.4 percent. The Twin Cities went below 3 percent, only to be done one better by Billings, Mont., at an estimated 2.4 percent. In oil-boom parts of western North Dakota, vacancy rates in Williston, Dickinson and Minot are reportedly below 1 percent.

In Sioux Falls, S.D., rental vacancy rates fell from 11 percent in 2010 to 4.6 percent last year. Dan Siefken, executive director of the South Dakota Multi-Housing Association, said tenant turnover in apartments is similarly low because “if you’re going to move, you have to have some place to go” that meets your household needs. “It’s like a game of musical chairs, and all the chairs are taken.”

Sources generally see green pastures for rental property owners. New construction in multifamily units is starting to swing upward, but not so fast as to overwhelm low vacancy rates, at least not immediately. Rents have started to rise, and that’s expected to continue. Of course, that’s not great news for renters; tighter vacancies and higher rents are particularly problematic for low-income renters.

How long these conditions might last is a matter of debate and will be affected by how aggressively the market responds to tight rental conditions, as well as the performance of the economy itself. It will also depend on the level of scarring inflicted by the housing market collapse on the American Dream of homeownership. Sources widely agreed that the recession and housing crash have changed people’s view toward homeownership. But there is much less agreement on whether that is temporary, and where homeownership rates will ultimately settle.

No vacancy

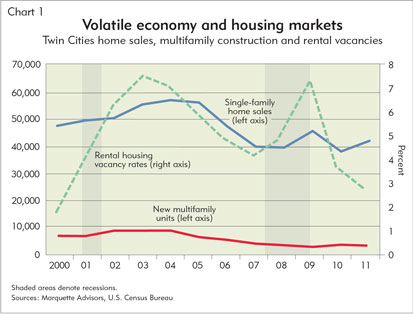

Rental markets might feel like they are owed a few decent years after surviving the past decade. The 2001 recession pushed vacancy rates up in many markets (see Chart 1 for Twin Cities illustration). Afterward, construction of new rental units grew in many places, and vacancy rates declined during the housing boom—both good indicators of industry health—but landlords were competing with a household preference to own rather than rent, making it hard to raise rents. In fact, strong growth in new rental units forced many landlords to offer incentives—first month free, no security deposit—to attract and retain renters.

Then the Great Recession hit and rental vacancies spiked again, climbing over 7 percent in the Twin Cities (see Chart 1). “The recession hit [rental markets] on both ends,” said Mary Rippe, president of the Minnesota Multi Housing Association (MMHA). Rampant job loss in 2008 and 2009, along with a soft market for college grads, forced many renters to consolidate in some fashion by moving to smaller apartments, doubling up with friends or moving back in with parents—or, for some older adults, taking a spare bedroom in their kids’ homes.

The rental market was also the unfortunate victim of the federal government’s first-time home-buyer program, which gave nonhomeowners an $8,000 incentive to buy in hopes of jump-starting the home-purchase market, pulling away more would-be renters. “So we were losing everyone on that end too, many of them long-time renters,” said Rippe. “We lost market share across the board.”

From this point, given the sluggish economic recovery and a moribund housing sector, a quick rebound in the rental market seemed like wishful thinking. But fast-forward two short years, and the Twin Cities overall vacancy rate (and 32 of 54 submarkets) had dipped below 3 percent last year, according to Marquette Advisors, a real estate services firm.

It’s a similar-but-different story across the largest cities in the Ninth District examined by the fedgazette (see Chart 2). Getting a strong handle on individual rental markets can be challenging. Centralized data are hard to find on many basic elements like rent levels and vacancy rates in most markets, especially outside the Twin Cities.

Available data and anecdotes suggest strong rental property markets across the district, even if vacancy rates are not identical. In the Chippewa Valley region of Wisconsin, home to Eau Claire, rental vacancies sat “around 5 percent” this spring and have come down considerably from about 15 percent in 2008, according to Dale Goshaw, president of the Chippewa Valley Apartment Association.

Even locations little affected by the recession have followed a similar path. Unemployment in Grand Forks, N.D., has been consistently below 5 percent for better than a decade. Its typical vacancy rate runs about 5 percent to 6 percent, according to John Colter, association executive of the Grand Forks Board of Realtors. But vacancies had been on the rise, hitting 9 percent as recently as early 2011, Colter said, mostly because of a couple of major new multifamily developments that opened in the market.

Demand gobbled up that supply, and then some. In February of this year, vacancies in the Grand Forks area were “a little north of 3 percent, so it’s really tight. … It kind of surprised me,” Colter said.

That’s almost soft compared with the western part of the state, where the oil boom has put a premium on anything with a roof. In Williston, a typical two-bedroom unit used to rent for $500 to $600 a month and today goes for $1,200 to $1,400, according to Neal Eriksmoen, president of Appraisal Services of Fargo, who does appraisal work across the state. “Those on limited income can’t live there anymore.” (For more discussion of housing in the oil patch, see the April 2012 fedgazette.)

The breakneck pace of activity in the oil patch makes it an anomaly, and in more industry sectors than rental housing. But it’s not the only region that has faced a fairly tight rental supply for a number of years. For example, a late-summer survey last year in Mankato, Minn., of more than 1,100 rental units (about 13 percent of that market) found exactly two market-rate units available for rent. “Our vacancy rate has never been high,” said Patti Ziegler, housing program coordinator for the city of Mankato. Three other surveys between 2006 and 2010 found vacancy rates between 1.7 percent and 4.9 percent.

Supply clues

In light of a weak recovery, the current tightness in rental units might seem unusual. But it’s no fluke, because the sector’s fundamentals are solid—in large part because of events that stem from the recession. For example, persistently high rates of home foreclosure are creating steady new demand for apartments, and the housing collapse has kept many would-be home buyers on the sidelines—in their apartments or looking for one. Positive (if slow) job growth since the recession is also generating some rental demand.

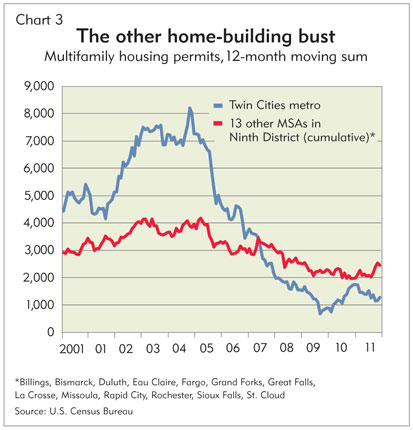

This steady rental demand is running headlong into a dearth of available units, the result of a near shutdown in new construction after the recession. For example, across the dozens of municipalities in the Twin Cities region, multifamily building permits plunged from more than 7,000 units annually from 2002 to 2004 to about 950 units in 2009 (see Chart 3). To give that number some context, Minneapolis alone averaged more than 1,000 units on an annual basis from 2002 to 2006. But it, too, followed the same pattern. During one 12-month period from late 2008 into 2009, the city approved permits for just 15 multifamily units.

Elsewhere across the Ninth District, permits appear to take a slightly less steep path—dropping by about half of their peak. But that’s due in part to stable building activity in a couple of markets with lots of renters. Fargo, for example, experienced phenomenal growth in rental housing, averaging more than 1,000 units betwen 2002 and 2005. Yet when the boom wore off, the region simply went back to its long-run average of about 600 units. Last year, it was back up to 900 units.

“North Dakota is its own ecosystem. It’s not necessarily recession-proof, but just about. And Fargo just keeps rolling along,” said Eriksmoen, who has conducted a local rental survey for about 20 years. “When the market here goes flat, that’s our downturn.” Rental vacancies were above 7 percent in 2007 thanks to the surge in new units. Despite continued building, the region’s vacancy rate has slowly trundled lower, hitting 4.1 percent in the first quarter of this year, according to Eriksmoen.

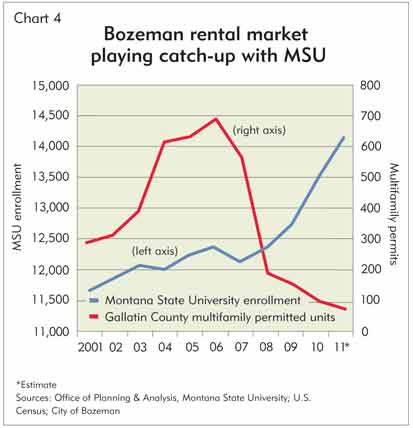

Other cities that failed to keep building, even those with large rental housing sectors, appear to be getting squeezed more tightly. Bozeman, Mont., is 56 percent rental housing, yet had a vacancy rate of 1.8 percent last year, according to a March housing study there. The squeeze comes in large part from an enrollment boom at Montana State University, combined with a crash in the number of multifamily units built in Bozeman and nearby communities in Gallatin County, from a peak of almost 700 units to mere dozens last year (see Chart 4).

Compounding the supply problem in many cities: While new construction hibernated, demolition hammers were still busy. The exact toll is hard to calculate. “Among data we wish we had are how many units are lost every year,” said Mark Obrinsky, vice president of research and chief economist at the National Multi Housing Council (NMHC), which represents large apartment firms nationwide. The organization has estimated that somewhere around 100,000 units are lost from aging and other factors across the country every year, or about 0.75 percent of existing supply. At that rate, the number of units coming into the market in 2008 and 2009 “was kind of like a net zero,” Obrinsky said.

Local checks suggest something similar. Minneapolis saw the demolition of close to 1,100 units of multifamily housing (and about 250 single-family homes) from 2007 to 2011, according to annual Minneapolis Trends reports. With little new construction and a fair amount of demolition, Duluth, Minn., saw a cumulative net loss of 40 rental units from 2009 to 2011, according to an April city housing report.

Add it all up, and it wouldn’t have been difficult to predict the current tight environment. Obrinsky said it was widely believed that “we were going to see a mismatch in a fairly short period” from a shortfall of renters to a scarcity of rental units. “Two years ago, people were optimistic about where we’d be right now.”

Outlook: Good times

Given some of the fundamentals, people on the business end of rental markets are upbeat across the district and the nation.

In Billings, Mont., rental vacancies peaked in 2009 at around 6 percent—a comparatively low peak attributable to the fact that the city “never saw super-strong growth” before the recession and has thus not experienced the vacancy pain seen elsewhere, according to Howard Sumner, a real estate consultant there who has gathered local rental market data for 30 years. Vacancies have since plunged to 2.4 percent, with the number of available units advertised in late April down 17 percent from the same period a year ago.

Sumner himself owns a number of rental units, including a 12-unit property he bought this spring. “I believe we’ve turned the corner and are now on the up-slope, and that’s where you make your money.” Sumner said development of new units “is just starting to get its feet under itself.” He has heard some talk of an outside developer building as many as 1,000 units, “but nobody intelligent would go and build that many. … You need strong increases in cash flow before you can justify the increase in new units.”

Renters in most cities can expect upward pressure on rents going forward, though rent increases are cushioned by the fact that they have been particularly modest since the recession, and longer in some markets (see sidebar). Sumner projects rent increases of 5 percent to 8 percent in Billings over the next 12 months. Twin Cities rent is predicted to increase about 5 percent for this year and next, thanks to vacancy rates that are expected to remain below 4 percent, according to CBRE, a real estate consultancy.

Development of new units has started to stir as a result. The number of new units has not fully rebounded to prerecession levels in the Twin Cities, MMHA’s Rippe said, “but there’s a lot in the pipeline being proposed.” More than 300 units were permitted in January this year in the Twin Cities, and there are whispers that as many as 2,000 new units might get built, most of them in downtown and uptown Minneapolis. “I think the rental market is cautiously optimistic. We’re doing a whole lot better than we were two years ago.”

Demand is also expected to stay strong. Home foreclosures have been a big source of new renters. Though foreclosures dipped slightly in 2011, they are nonetheless expected to remain elevated and possibly even increase again this year. Banks repossessed fewer properties in 2011 compared with 2010, due in large part to the investigations surrounding so-called robo-signings and bank foreclosure procedures, which delayed foreclosure processing, according to RealtyTrac, an online foreclosure clearinghouse. (High foreclosures have also led to an increase in owner-occupied homes being converted to rental units. For more information on this trend, see sidebar article.)

Should robust job creation ever return, there is also considerable pent-up demand waiting to be unleashed on the rental market, as the household consolidation forced on many by the recession gets reversed. The large millennial generation also is moving into prime household-forming years, and many have been forced to live with roommates or, worse, parents. A recent Pew survey found that 39 percent of all adults ages 18 to 34 say they either live with their parents now or moved back in temporarily in recent years.

A March 2012 report by the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts points out that the normal rate of household formation—from population growth, children moving from parents’ homes, divorce and other demographic events—is a little over 1 percent annually. Over the past four years, however, annual household growth has been half that rate. Some level of restrained demand is normal during recessions, but NAREIT’s review of 50 years of data suggests that current pent-up demand was three times higher at this point compared with past recoveries, and represented approximately 2 million households.

Cyclical or temporary?

Many sources also believe there is a new wild card in play—namely, the effect of the recession and housing slump on people’s attitude toward homeownership.

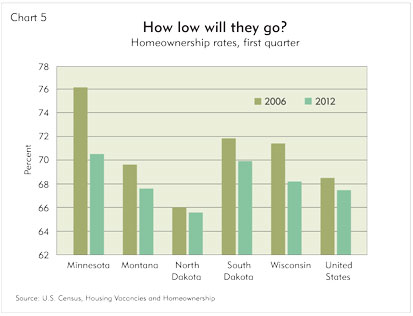

At the national level, homeownership grew from 65 percent of all households in 1995 to 69 percent in 2005. Today, it’s back to a shade over 65 percent, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures. Rates in the Ninth District generally have followed the same slope (see Chart 5). Minnesota’s homeownership rate, among the highest in the country in 2005, has witnessed a particularly long slide.

Whether or not this is a cyclical, temporary shift or a more permanent one with lower homeownership and higher renter levels will be revealed over time. In the meantime, there’s a fair amount of crystal ball reading.

Many believe that renting will grow over the next few years. A report by the Urban Land Institute called existing apartment owners “golden.” All signs, it said, “point to more Americans renting and a further decline in homeownership as defaults on mortgages and foreclosures continue.” Tighter lending standards with high down payments will also keep prospective home buyers in their apartments.

Local sources concurred. “I think there’s a shift in the mood” toward renting, said Rippe, from the MMHA. “Now, first-time home buyers are reassessing whether that’s what they want.”

That opinion is popular, but not universal. Steve Pelto, owner of Look Realty in Marquette, Mich., said he believes that home buying is a “trend that seems to be coming back. People are reaching the conclusion that to own a home is cheaper than you can rent.” At prevailing rates, the mortgage payment on a $130,000 home would be less than $600 a month. Some have complained about the difficulty of qualifying for a mortgage, but Pelto said he has one client looking at an average house, “and I have two bankers fighting over the mortgage.”

Falling home prices might eventually pull many renters back into the ownership market, “but not right now,” said Obrinsky, from NMHC. “There’s no reason to rush back into the market.” He pointed out that homeownership-to-rent ratios don’t correlate very well with prices. When home prices are going up, affordability goes down, but people keep buying because they don’t want to wait to buy and have to pay more. The inverse is also true: As prices fall, affordability improves, “but no one is buying a house” because there is little danger in waiting, Obrinsky said.

Siefken, from the South Dakota MHA, is himself a long-time renter and property owner, and has long believed in the value proposition of renting. “I was the odd man out for a lot of years,” he acknowledged. But there’s more than meets the eye in a low mortgage payment.

“[Renters] seem to understand that for $750 in rent, you’re not going to get a house for that” because there are myriad other costs to ownership, including property taxes, insurance, upkeep and in some cases utility bills that were previously included with rent. The cost relationship “was not always clear in the past, and it didn’t need to be” because homeowners could just sell at a profit if things ended up being too expensive, Siefken said. Those days are gone, and would-be buyers have been chastened by the glut of underwater homeowners who can’t get out from underneath their mortgage.

That mindset is a large part of the business model for Brent Hayden, CEO and founder of Renter’s Warehouse, of Golden Valley, Minn., which was named the largest and fastest growing property management company in Minnesota by Inc. magazine.

The company was started in 2007 and manages about 1,500 rental units on behalf of property owners, all within about a 75-mile radius of the Twin Cities. The large majority are single-family homes, condos and town homes, according to Hayden—many of them “unintentional accidental” owners who bought a house and now need to sell it, but can’t find a buyer. So they turn to Renter’s Warehouse, where they find willing (and screened) renters.

“Renting is becoming the new big thing,” said Hayden, who is 28 years old. “Right now, it’s not cool to be a homeowner. My generation isn’t a homeowner. It’s foolish to own a home if you’re going to leave in less than five years” because you won’t leave with any equity. Hayden expects rents to go up this year and that market conditions “will be the best they’ve been in 10 years.” He believes the rental market is on a five- to seven-year growth cycle. “It’s the best time to be a landlord.”

Many others are optimistic, but less willing to look quite that far out. “This year and next will be very good years,” Obrinsky said. Two years from now, he said, “is sort of wait and see,” depending on job growth and the market’s reaction to tight vacancies. “Many believe we’ll start to see new units pick up in a substantial way.”

On the question of how far ownership rates might fall, “we see the same division [of opinion] in our industry,” Obrinsky said. “We’re inclined to think there is potential for a long-term shift. It’s not going to go to two-thirds rental, but small changes can mean big things” for the industry.

Some have suggested that the national rate of homeownership might go to 60 percent. “I’m skeptical it will go that low, even on an interim basis, but I can’t rule it out. Things that you thought couldn’t happen before have.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.