Staff at the University Children’s Learning Center on the campus of the University of North Dakota were nervous when state evaluators walked through their door. But by the time the evaluators’ work was done, staff members were excited to apply the lessons they’d learned.

“Our staff loved the opportunity to learn how to be even more intentional in how we relate to our kids,” Dawnita Nilles, the center’s director, said. “We’ve learned a lot about how to encourage our kids to be more critical thinkers.”

The evaluators came from Bright & Early, North Dakota’s child care quality rating and improvement system (QRIS). The “quality” in QRIS refers to program characteristics consistent with fostering healthy child development, such as skilled teachers, research-based curricula, and parent engagement.

Every state in the Ninth Federal Reserve District has rolled out its own version of a QRIS except for South Dakota, where QRIS planning is currently under way. These systems aim to establish standards of quality in the child care field to provide parents, policymakers, and child care providers with information for crucial decisions about the future of their children, their communities, and their businesses. (For a discussion of what entities make up the child care field, see the “What do we mean by child care?” sidebar below.)

Looking broadly at the rollout of QRISs across the country, early evaluations have been mixed. Independent validation studies of QRIS rating tiers generally demonstrate positive associations between the stated rating and the observed level of quality. In other words, when independent assessors observe quality-rated providers in action, their findings likely reflect the child care provider’s QRIS rating.

However, in terms of child outcomes, QRIS rating tiers have not necessarily translated into increased school readiness—that is, higher-rated programs have not consistently shown stronger child outcomes compared with lower-rated programs. This has led some states to make changes in rating criteria based on recent research and other feedback.

This article discusses the rationale and structures underlying QRISs. It also covers the history of QRISs in the Ninth District and discusses various ways they struggle and succeed in supporting states’ goals to connect more families to high-quality child care. As a relatively new and still-evolving innovation, QRISs are in a position to make adjustments to better meet these goals.

The brain-development case for QRISs

In 2014, Congress reauthorized the Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG), a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services program that helps fund state-run child care subsidies. (For more on this, see the “What is a child care subsidy?” sidebar linked below.) When it did so, it required states to direct a greater percentage of funds toward activities that support quality. States can meet this requirement by applying some of their CCDBG dollars to administer QRISs.

CCDBG funds fall short of covering the full cost of either of these intended uses. As a result, many states also pay for QRISs through general fund revenues and, in some cases, through public-private partnerships.

The shift in CCDBG policy is an example of the increasing visibility and popularity of QRISs in public policy circles. This is occurring in some part because policymakers at every level are more aware that child care quality plays an important role in supporting child development.

Interactions between children and caregivers during children’s earliest years have important implications for brain development. Neuroscientists and psychologists can point to research showing that excessive stress during early childhood affects the wiring of a child’s brain, impacting the ability to learn, form memories, and self-regulate.1

By contrast, when children grow up in stable, nurturing, and enriching environments, they are less likely to succumb to adverse circumstances later. High-quality child care can support healthy child development, and its benefits can stretch into adolescence and beyond.

Research shows that children from disadvantaged environments who attend high-quality child care are likely to perform better in school, achieve higher levels of education, and earn more money than similarly disadvantaged children who do not attend high-quality care. They are also less likely to be convicted of a crime, become a teen parent, or access the social services safety net.2

Even without reading the growing stack of research on early childhood education, most parents would probably express a preference for high-quality care for their children. But how can parents identify the best options in their area? And how can child care providers find out what constitutes high quality in their field? QRISs aim to address both of these issues.

Developing a QRIS

QRISs attempt to connect research on child care quality with the real world by defining high-quality child care and identifying the providers that offer it.

The systems tend to have four or five tiers. Tier requirements vary among states, but all go beyond the standard “health and safety” requirements of a child care license. For example, Montana’s QRIS, Best Beginnings STARS to Quality, has five categories of criteria that are labeled Education, Qualifications, and Training; Family/Community Partnerships; High-Quality Supportive Environments; Leadership and Program Management; and Staff-to-Child Ratios and Group Size.

Developing the standards is often an iterative process involving state government officials, expert advisors, early childhood teachers, and child care program directors. After the development of an initial set of standards informed by stakeholders and research, a state QRIS effort typically starts with a pilot program operating in a few counties or cities.

Minnesota’s QRIS, Parent Aware, was piloted by the Minnesota Early Learning Foundation, a nonprofit organization with a board representing a number of state business leaders. The privately funded pilot was implemented in two urban areas, a suburban community, and a rural area. Following the pilot, the state was awarded a $45 million Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge grant from the federal government.3 Part of these funds supported a statewide rollout of Parent Aware over a four-year period.

By starting with a pilot, states can identify issues unique to their child care market and work to craft a QRIS that is responsive to parent and provider circumstances. For example, Montana used its pilot period to begin addressing some of the more challenging aspects of serving the more remotely located child care providers of its state.

QRISs in the Ninth District

|

|

Michigan |

|

Minnesota |

|

|

Montana |

|

|

North Dakota |

|

|

Wisconsin |

Once a rating system is established and providers are signed up, states must decide how often a provider has to re-apply to a QRIS to improve or hold steady its rating. In Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, a provider’s rating is valid for two years; in Montana, all providers must renew annually. In North Dakota, providers’ renewal time frames vary according to their rating levels. Programs that receive Bright & Early’s lowest rating, or Step 1, must renew annually, while programs rated Step 2, 3, or 4 are able to renew on a three-year basis.

Given limited resources and staff time, states and their partners must often balance their efforts to recruit new QRIS members, maintain and renew current participants’ ratings, perform evaluations, and provide other services to parents and QRIS-rated providers.

Methodologies and adaptations

States in the Ninth District offer several ways for providers to attain, maintain, or improve their quality ratings. The different rating methodologies are intended to reflect the diversity of the child care market. For example, providers that have already achieved a pre-approved national accreditation are often offered a “fast track” for high QRIS ratings.

Other providers may be required to have their staff attend trainings or attain credentials, and develop a curriculum. Depending on the state, providers may choose from a list of pre-approved, research-backed curricula.

In North Dakota, providers aren’t required to use specific curricula. Instead, they complete an 11-page workbook that demonstrates how the curriculum they use matches up with the early learning guidelines articulated by Bright & Early.

States can also include other criteria for providers. For example, Wisconsin’s QRIS, YoungStar, requires providers to describe their business practices. In some states, providers are required to demonstrate a plan for parental engagement. QRISs may also give providers points for adopting culturally reflective practices.

QRISs can adapt as research provides further information about what creates a high-quality child care environment. As researchers learn more about what constitutes high-quality care, state QRIS administrators should be sure to incorporate newly identified best practices into their ratings, says Cindi Yang, director of Child Care Services at Minnesota’s Department of Human Services.

“Opportunities to improve don’t end when you achieve the highest rating in Parent Aware,” she added.

Connecting parents with quality child care providers

Nationwide, nearly two-thirds of children under age 6 have all parents in the labor force. Rates are even higher for children in most Ninth District states. (See Figure 1.)

Consistent child care is important for the economic stability of these families. Yet according to the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health, about 8 percent of respondents with a child under age 6 reported that they or someone in their family had to quit, not take, or greatly change a job because of problems with child care during the past 12 months.4 By connecting families to quality-related information that helps them find highly rated care for their children, QRISs provide an important service for working parents.

To increase parental awareness, several states give free promotional materials to QRIS-rated providers. In cities in Minnesota with high QRIS-participation rates, purple yard signs, posters, and banners trumpeting Parent Aware ratings are a common sight on churches, child care centers, and family child care providers’ homes.

QRISs can also improve parents’ ability to access quality care by making child care providers’ quality ratings easily available to the public. Websites for state QRISs can bring the child care shopping experience into the digital era. At websites like ParentAware.org, parents can find contact and rating information for all the licensed child care providers in their area.

Ericca Maas of Minnesota’s Close Gaps by 5, an advocacy organization that promotes Parent Aware, highlighted public awareness as a high-impact area for private investment.

Business leaders have an inherent interest in child care because they care about the development of the future workforce,” she says. “Private philanthropy can fill in the gaps of expertise in the public sector—by providing and producing advertisements for QRISs, for example.”

In Wisconsin, the Department of Children and Families’ communications director, Joe Scialfa, echoed this idea. He mentioned the state’s CETE (Children’s Empowerment Through Education) network, which brings organizations in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors together to work on increasing the supply of quality child care.5 The collaborative process that fed into the rollout of YoungStar created an advocacy base for the program that transcends any particular sector.

“The early childhood development community can’t do all the heavy lifting on its own,” he said. “Success will require working across silos.”

Increasing the supply of high-quality care

QRISs help parents identify the highest-quality child care providers, but in many areas highly rated providers are few and far between. That’s why QRISs are also designed to increase an area’s supply of quality providers by offering resources to improve child care practices.

QRISs invest significant resources in helping increase professional development for their states’ child care workforce. That can take the form of visits from consultants and trainers, online learning opportunities, or partnerships with community colleges and universities.

QRISs can also create opportunities for providers to communicate through informal networks and learn from each other.

“Provider networking is a very critical part of the experience, so we create space for providers to do that,” said Minnesota’s Yang. In North Dakota, Bright & Early even uses a cohort model, creating additional connections for child care professionals.

Providers can also offer critical information to QRIS administrators, especially when QRISs are first piloted. For example, providers may feel that information about a requirement is hard to find, or that certain requirements are overly burdensome. Systems can ease such “growing pains” by soliciting input as they transition from theory to practice.

Rhonda Schwenke, lead specialist for Montana’s STARS to Quality QRIS, recalled hearing from providers frequently during the rollout of the system. “We incorporated a lot of provider feedback,” she said, adding that the responsiveness helped maintain and spread interest in the program.

“We want to lift up and recognize the providers and programs that are doing good things for children, and in turn that gives more parents the option to choose a high-quality program for their child,” said Pam Palmer, program manager at Bright & Early. “Our goal is to help both providers and parents understand and access quality.”

Barriers and interventions

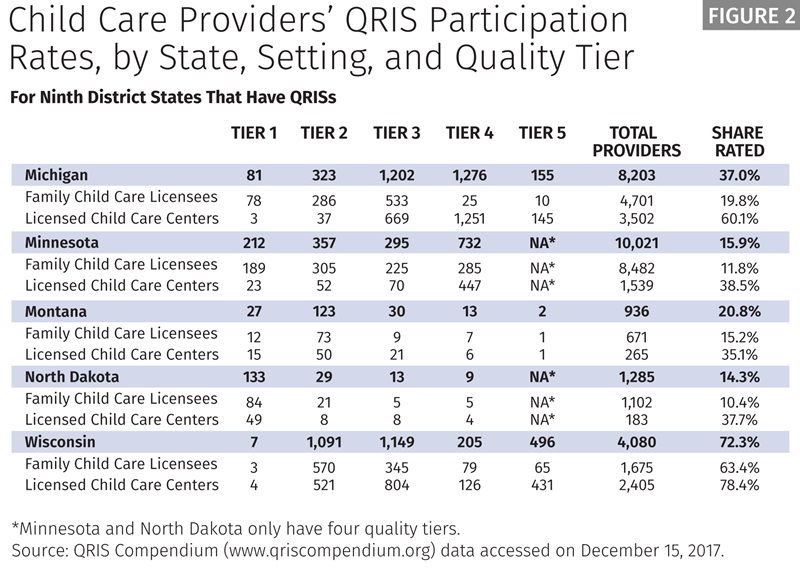

Efforts to increase the supply of high-quality child care ultimately hinge on participation by licensed child care providers. QRIS participation is not mandatory in Ninth District states. Provider participation rates vary widely across the district, heavily influenced by geography, provider type, and other state policy choices.

“In our most populated urban county, we’re hearing providers requesting training because parents have asked about it,” said Palmer. “We haven’t seen it as much in our more rural areas.”

One way to measure the spread of a QRIS is to calculate a state’s participation rate by dividing the number of QRIS-rated providers by the number of potentially rate-able licensed child care providers in a state and then converting the number to a percentage. This approach demonstrates the wide range of participation across the Ninth District, even under well-established QRIS regimes.

Wisconsin’s 72 percent participation rate in YoungStar is the highest in the Ninth District. Michigan’s QRIS, Great Start to Quality, has the second-highest participation rate (37 percent). Minnesota lands a distant third with a provider participation rate of 16 percent. (For more on QRIS participation rates in the district, see Figure 2.)

Important differences in Ninth District states’ geographies, child care markets, and child care subsidy policies explain part of this large gap. For example, child care centers have a higher participation rate in QRISs than family child care providers do—and the child care markets of Wisconsin and Michigan have a much higher share of child care centers than the other states in the district have. In fact, Wisconsin has more child care centers (1,900) than family child care providers (1,700). By contrast, Minnesota has about 1,500 child care centers and 8,500 family child care providers.6 (See the sidebar “What do we mean by child care?” below for more information on the differences between child care centers and family child care providers.)

While QRISs are designed with all care settings in mind, family child care providers’ participation rates remain comparatively low for a number of reasons. Attending QRIS trainings or information sessions can be difficult or costly when a provider has limited staff. Family providers also tend to be more common in rural areas, where access to training or QRIS staff can be challenging.

Anecdotally, a shortage of child care providers may also play a role. The number of customers shopping for child care has outpaced the supply in many markets, leading to long waiting lists, particularly for infant care. A child care provider that already maintains a waiting list has little profit-related incentive to become quality-rated, and may view the high demand as an affirmation of quality.

To facilitate participation among family child care providers and in rural areas, several states have developed distance-learning materials. State QRIS managers frequently collaborate with Child Care Resource and Referral networks in their state, thus adding to the QRIS’s capacity for outreach. In Minnesota, Parent Aware coaches meet with child care providers using video or phone calls. In Wisconsin, YoungStar incorporates local community colleges into its training programs.

Creating financial incentives for QRIS participation

Some states have encouraged QRIS participation by offering ratings-based incentive payments through their publicly funded child care subsidies. (See the “What is a child care subsidy?” sidebar linked above for more on how the subsidies work.). In an industry known for razor-thin margins, such so-called “quality differentials” can make the difference between a profit and a loss when a provider chooses to serve families that access child care subsidies.

Federal guidelines encourage states to set their reimbursement rates based on what the 75th percentile of the child care market charges for a child of the same age who receives the same type of care. Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin all fall well short of this guidepost. When a provider in one of these states serves a family that accesses child care subsidies, the base subsidy payment is often set far below what a typical provider charges a private-pay family.

For example, a child care center serving an infant in Hennepin County in Minnesota would be reimbursed a maximum of $1,161 per month through the state’s Child Care Assistance Program. But a typical child care center in that county may charge up to $1,542 for an infant—33 percent more than the maximum subsidy rate. However, if a center is rated as a 4-star provider under Parent Aware, its maximum reimbursement would increase to $1,394. That’s still short of the federally recognized market rate, but cuts the gap by more than half.

Wisconsin’s subsidy bonus system is unique in the Ninth District for two reasons: it requires any provider who accepts payments from the state’s Wisconsin Shares child care subsidy program to be quality-rated (a likely reason for Wisconsin’s relatively high participation rate) and is the only state child care subsidy program to penalize providers with a low rating by decreasing their reimbursement rate.

Tiered reimbursements aren’t the only policy lever available for encouraging providers to serve families that access child care subsidies. In Montana, all programs in STARS to Quality that are rated STAR 1 or higher are required to serve a certain percentage of “high-needs” children, with programs at STAR 4 and STAR 5 serving a higher percentage. Children who come from families using a state child care subsidy are considered part of the high-needs category.

QRISs’ impact: What we know so far

Data from QRISs can provide a framework to measure how different tiers of quality in child care programs affect children’s development and school readiness. The data can also inform policymakers on communities’ disparate access to quality care.

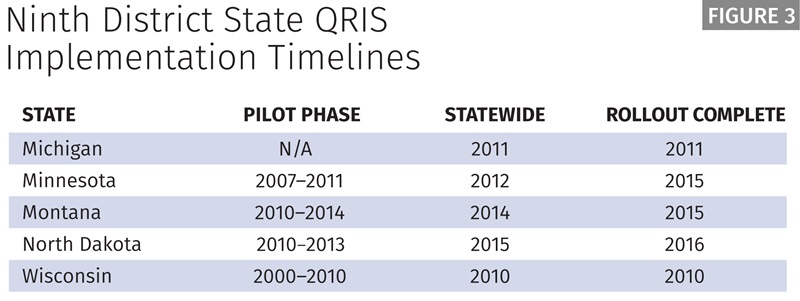

Such evaluations are beginning to take place in states that were early to adopt their QRIS models, including Minnesota and Wisconsin, which started their statewide rollouts more than five years ago. (For more information on Ninth District states’ rollout time frames, see Figure 3.)

Minnesota and Wisconsin have undergone their first validation studies, which both affirmed that QRIS rating tiers are associated with observable quality. In other words, providers with higher ratings demonstrate higher quality based on independent assessments. In Minnesota, however, evaluators found this relationship only with child care centers, not family child care providers.

The relationship between QRIS rating tiers and child outcomes is less consistent. For example, in Minnesota, evaluators found that children attending higher-rated providers made greater gains on social competence and attention/persistence (a measure of children’s approach to learning) compared with children attending lower-rated providers. However, findings linking children’s development and Parent Aware ratings were not pervasive across every outcome the evaluators considered. The authors note there were associations in the expected direction on three of the five developmental domains examined.7

Meanwhile, in Wisconsin, a separate evaluation effort found no significant differences in school readiness between 2-star providers and providers with 3 or more stars.8 (Despite the state’s relatively high overall participation rate, a small sample size of 4- and 5-star programs made it difficult for researchers to draw conclusions about differences among the higher-rated programs.) Validation studies of QRISs in states outside the Ninth District have found somewhat similar results. That is, QRIS ratings are more often associated with improvements in quality measures, such as safety, materials, and teacher credentials, than with improvements in child outcomes.

However, QRISs can make adjustments to strengthen the linkages between the dimensions of child care they assess and the goals of improving children’s early skills and behavior. While early childhood research is still evolving, findings to date can provide guidance on program characteristics consistent with positive child outcomes.9 QRIS systems can incorporate these findings and be prepared to integrate new learning as it becomes available. In addition, incorporating feedback from stakeholders could improve the efficiency and usability of QRISs for parents and providers.

As an example, Minnesota recently updated its rating criteria, coaching model, and rating process by considering the Parent Aware validation study results alongside feedback from more than 900 individuals, including state and national experts, local child care program directors, and parents. Administrators made sure the group included people of color and recent immigrants.

Studies can also measure the supply of quality care in specific communities, including access to highly rated providers. For example, an analysis by the Minneapolis Fed and the Badger Institute found that in Wisconsin, children living in areas with higher poverty rates and rural areas were less likely to live near highly rated YoungStar providers.10

In Montana, Rhonda Schwenke also thinks evaluations could demonstrate the ways that QRISs can benefit providers. “We’re anticipating that the professional development and other opportunities presented by STARS to Quality will lower turnover rates and may yield other returns on investment for our providers,” she said.

A tool for focusing on what matters

The nuances of each state’s QRIS demonstrate the particular challenges— and opportunities—the child care economies in Ninth District states face. Meanwhile, the support for QRISs by governments, philanthropists, and businesses is evidence of the growing recognition that facing those challenges will be crucial to how each state’s young minds and local businesses develop.

States with a QRIS have a tool that can inform parents, gather data, and support child care providers. Ideally, the systems will inform policymakers about ways to give children more access to nurturing and supportive care while their parents are working. At the same time, QRISs can be responsive to validation study findings and early childhood research to create stronger linkages between rating criteria and better child outcomes.

As Dawnita Nilles pointed out, a QRIS provides a great opportunity for parents and practitioners to focus on what really matters.

“Bright & Early forced us as a team to stop and think about why we do the things we do in our curriculum,” she said. “What do we stand for, and how does our curriculum get us there?”

“It’s actually quite fun once you get over the fear,” she added.

Endnotes

1 Key Concepts: Toxic Stress, Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University.

2 For more on this research, see Rob Grunewald, “Investments in Young Children Yield High Public Returns,” Cascade, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Fall 2016.

3 In 2011, Minnesota was one of nine states to receive the first Race to the Top-Early Learning Challenge (RTT-ELC) grants (https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ecd/early-learning/race-to-the-top). Administered by the Administration for Children and Families in cooperation with the Department of Education’s Office of Early Learning, RTT-ELC supports states’ efforts to increase the number of disadvantaged children enrolled in high-quality early learning programs, design and implement integrated systems of programs and services, and enhance data systems and assessments.

4 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health data query, Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health, Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (www.cahmi.org). Retrieved [10/31/17] from www.childhealthdata.org.

5 Cete also means “a group of badgers”—a nod to the state’s mascot. For more on CETE, visit cetewisconsin.org.

6 The Quality Compendium. Retrieved [12/15/17] from qualitycompendium.org.

7 Kathryn Tout, Jennifer Cleveland, Weilin Li, Rebecca Starr, Margaret Soli, and Erin Bultinck, The Parent Aware Evaluation: Initial Validation Report, Child Trends, February 2016.

8 Katherine Magnuson and Ying-Chun Lin, Validation of the QRIS YoungStar’s Rating Scale. Report 2: Wisconsin Early Child Care Study Findings on the Validity of YoungStar Rating for Children’s School Readiness. UW-Madison, School of Social Work and Institute for Research on Poverty, March 2016.

9 Rob Grunewald, “Sustaining early childhood education gains,” Community Dividend, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, February 2016.

10 Rob Grunewald and Michael Jahr, Rating YoungStar, Wisconsin Public Research Institute (WPRI) Report, June 2017, Vol. 30, No. 2. (The WPRI was renamed the Badger Institute in late 2017).