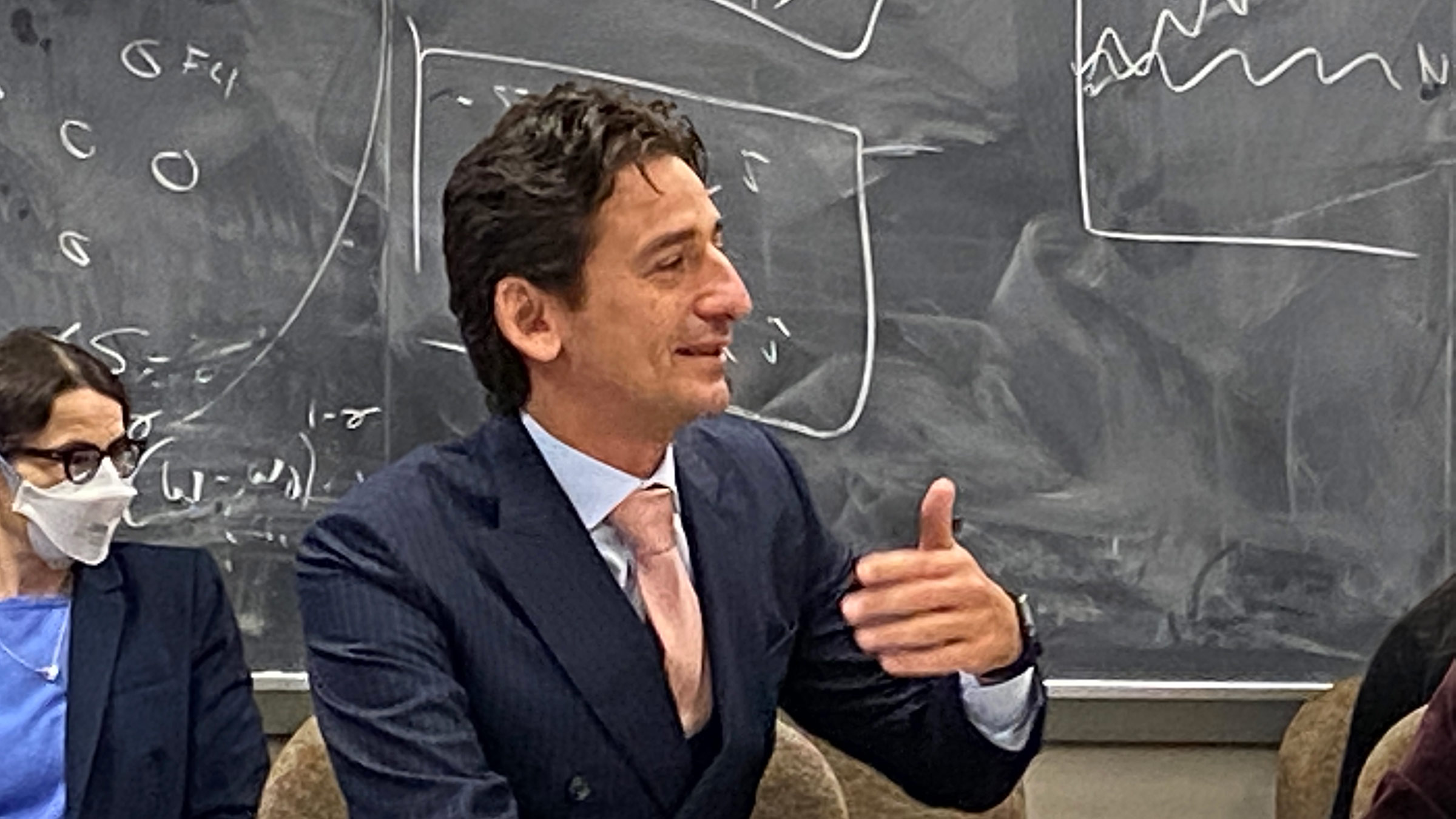

A career-long “Fed person,” Minneapolis Fed Director of Research Andrea Raffo lights up describing “the beauty of the Federal Reserve System” for economic research.

The Minneapolis Fed’s on-staff research economists and monetary advisors, along with a cadre of consulting economists, pursue their own academic passions while staying closely plugged in to the Fed’s monetary policy work. When Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari or others on the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raise a pressing question, Raffo said, “we may have the expert who already knows the literature and who has contributed to it. We may also have the talented researcher who says, ‘I can take that on. I can use my framework, my model, to analyze the data and give you an answer.’”

Economists, in turn, take inspiration from policy discussions to shape their independent research agendas. “This two-way process, these synergies, are the secret behind the success of the research division,” Raffo said. Two of his own major papers were inspired by questions posed by former Fed Chairs Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen.

Raffo took the helm of the Minneapolis Fed’s storied research division in August 2022, after serving as associate director of the Division of International Finance at the Fed Board of Governors. His passion for research extends to his off-hours, when he practices as a certified wine instructor.

What attracted you to the Minneapolis Fed and our research department?

The research department here needs no introduction, and it is world famous for the quality of research that it conducts. It has a long history of excellent research that goes back to the ’70s and a synergy with the University of Minnesota in terms of conducting pure, academic-style research that pushes the boundaries of the frontier. It’s no coincidence that we have seen a number of Nobel prize winners spend a large part of their careers at the Minneapolis Fed. These great minds changed the way we think about macroeconomics, and the language that they established is basically what we teach today in grad school.

So, I have always considered it a center of excellence. I visited the Minneapolis Fed a number of times in the past to spend the week, present my research, get feedback, and interact with these top researchers. I always had a fantastic experience. There is just an atmosphere of curiosity and dedication to research that is difficult to find everywhere.

A second reason for me was President Kashkari. I had seen him in action when I was at the Board of Governors, and I started looking into his speeches and public interactions. He has a vision, and you can see that he has a passion for what he does. He has a way of thinking about the world that is, in some dimensions, nonstandard for an economist—in a good way. And he is a great communicator, always trying to make sure that our Fed jargon becomes accessible to the public. I thought, I can learn a lot from this experience and working closely with Neel.

Last, but not least, is the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute, which is a unique opportunity within the Federal Reserve System. The economy has changed a lot over the past 30 or 40 years, and issues about inequality and labor market opportunities have come front and center in the public debate. Neel’s vision was to create a center that would play a leadership role within the Federal Reserve System and in the U.S. to produce frontier research on these issues. It’s a hub for talented economists—but not only economists, opening the discussion to fields that are typically running parallel to the economic field, like sociologists and lawyers. We just celebrated the fifth anniversary of the Institute, and I think it’s off to a great start. I can see more success coming down, and I look forward to contributing to the next five years.

You spent 15 years as an economist with the Board of Governors. How does that experience inform your work now that you are at one of the regional Reserve Banks?

I define myself as a Fed person. When I was in graduate school at UCLA, I had a summer internship in the research department of the Atlanta Fed and I remember telling myself: Wow, this is a great environment. You do the same academic-style research that you do in a university. But then instead of teaching, you provide inputs to policy discussion. I had a keen desire to study and practice policymaking, and that’s really what attracted me to the Federal Reserve.

My first job was at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, and then I moved to the Board of Governors. I consider those years as formative in terms of the economist that I am today. I started at the Board in 2007, so I went through the Lehman Brothers collapse and the global financial crisis. It felt like economists were in the trenches trying to figure out how to best revive the U.S. economy—actually, the global economy—in coordination with other central banks. I saw how many weekends people worked, how much they care about trying to serve and help produce better outcomes.

I was in the Division of International Finance, so my responsibility was to monitor developments in the European economies. Sure enough, not only did we go through the global financial crisis, we then went through the European debt crisis. That was an experience that gave me more opportunities to interact with the policymakers, to give briefings to Chair Bernanke and later to Chair Yellen on developments in these European economies and on policy challenges.

Another aspect in which my years at the Board of Governors were formative was in terms of management experience. That’s where I started first leading a team as a section chief and then became an officer. The more you move up on the org chart, the more you realize that every single word or behavior that you have in the workplace has a huge impact on all the people around you. It made me appreciate how important it is to convey a notion of mission, dedication, respect, equity. I look forward to applying some of the insights that I got out of my experience there as a leader here in Minneapolis.

As the research director, you play a key role with each cycle of the FOMC, which meets every six weeks. I understand those are very intense periods. Tell me about those weeks leading up to the FOMC and your role in advising the president.

In some dimensions, it is not very different from the policy cycles at the Board: There are conversations about how we see the economy, about what is the appropriate monetary policy stance, the trade-offs and implications of different courses of action.

Something that is different here in Minneapolis is that, to some extent, we take much of the input that the staff in D.C. produces as the starting point for our conversation. The economists in D.C. produce the “Tealbook,” which contains the Board of Governors’ staff views about what is happening in the U.S. economy, scenarios for risks the economy might face, and what different policy paths might imply for the U.S. economy. It’s not that we necessarily need to differ, but I see our job and our mission here in Minneapolis as providing a different perspective on some of the topics that are going to be discussed at the FOMC.

A lot of what economists do is to use economic models and try to figure out what those models are saying. In addition, an important activity here in Minneapolis is to reach out to the business community to understand what they are seeing on the ground: Is there anything that the aggregate data are missing? We talk to business leaders, we talk to the leaders of unions. This is another innovation that I think Neel brought to the table—he wants to reach out to a broader set of economic actors to get the input on how they see the economy.

That local outreach is a part of our deliberation process. It is a great input, which the folks in D.C. don’t get a chance to necessarily observe. We leverage it to a great extent here.

Can you think of something you heard in the course of those meetings with stakeholders in the Ninth District that helped you shine a different light on what you would’ve seen in the Tealbook?

Totally. We had one of our contacts who said, “Look: High inflation is very painful, and it’s actually hitting our community more than a recession.” I can tell you that we had a great deal of conversation around that statement, trying to dissect what we were hearing.

The typical way of thinking for economists is that recessions are very costly. Whenever we think about changing interest rates, the trade-offs are always between trying to bring down inflation—which right now is too high—and trying to minimize what is going to be the hit to the American economy and to the labor market. There is plenty of academic research showing that people who become unemployed, especially when they become long-term unemployed, receive a very deep and persistent hit to their set of opportunities. Those outcomes tend to be more concentrated, but they are very painful for communities and individuals that go through prolonged spells of unemployment. So that statement—that inflation was even more painful than recession—made us discuss and rethink the way we typically see some of the trade-offs.

This pandemic-era inflation has created what I imagine is a part-fascinating, part-terrifying moment for monetary policymaking. It doesn’t seem like you can fit this time into any obvious historical or other template. What are the critical questions that research is working to help policymakers understand right now?

You made a great observation that I would amplify: In the past couple of years, we experienced two 1-in-100-year events—a global pandemic and a war on European soil. If you think about being a policymaker and having to deal with uncertainty, a pandemic would be quite enough. But then adding the spillovers from the war in Europe amplifies the difficulties that we have faced.

On the inflation front, the biggest question we face is to what extent the actions that we have taken—including the prospective actions that we have signaled with the SEP (Summary of Economic Projections)—are enough to bring down inflation within more acceptable ranges. Is the tightening in monetary policy sufficient to bring down inflation without generating a recession? This is often called the “soft landing.”

Some of the fundamentals of the U.S. economy remain very strong, and the labor market is one piece of evidence in support of this claim. We have very low unemployment, and we see a large number of job vacancies relative to the number of people that are unemployed. We will have to observe a reduction in vacancies and perhaps tolerate some increase in unemployment to bring down inflation. So a lot of our research is going toward understanding to what extent we can reduce the amount of labor demand by largely reducing the number of vacancies with minimal impact on unemployment. There are a variety of opinions on the table, but one piece of research produced by one of our economists, Simon Mongey, provides some evidence in support of the soft landing view, which is encouraging.

In our policy discussions, we consistently, systematically have conversations about what are the possible risks. We do have our baseline view, but we know that there is uncertainty: If inflation does not fall as much as expected this year, how should monetary policy react? There is a “risk management” approach behind the forecast that is part of our operating procedures, I would say.

As you might imagine, it is difficult to predict which shocks might affect the economy. For the majority of 2021 and into 2022, for instance, we focused on our assumptions about the coronavirus—this was one of the risk assessments we would typically discuss. It’s just that certain events—like a war—are so much “in the tail” [of the probability distribution] that it’s like all bets are off. You have to rethink the playbook. You have to rethink how this event will change the way the economy operates.

You clearly view the war in Ukraine as a fundamental event shaping macroeconomic trends more widely.

Yes. Take the forecast of the International Monetary Fund as of October 2021, which is pre-war, or the forecast of the Fed’s December 2021 SEP, and compare those with their most recent forecasts. A large amount of the downward revision to global and U.S. GDP growth and upward revision to inflation has to do with the war: the direct hit to energy, commodity, and food markets; the delayed resolution of strains in the global supply-chain system; the hit to confidence—and, in response, the aggressive tightening of monetary policy around the world. It’s a very simple exercise, and it’s easy to see how big the hit of the war is on the global economy and the U.S. economy.

Your background is in international finance; here at the Minneapolis Fed we have a number of top economists with expertise on sovereign debt and international currency crises. How does this international view connect to the domestic mandate of the Fed?

Today, anything that happens in the global economy has implications for all economies around the world. The European debt crisis was an example of a debt crisis happening in an advanced economy, which by many metrics we would have considered safe. It had important implications for the U.S. economy in terms of exports and economic activity, inflation, exposure of the U.S. institutions to the European financial system, and it generally affected risk sentiment in global financial markets. I think that event was a critical moment that reminded us that the old view—that basically sovereign debt crises and currency crises were largely accidents along the way of development for emerging-market economies—was misplaced. Last fall, we saw turmoil in the U.K. bond market, which looked a lot like an episode that we could have observed for an emerging market in the late 1990s. It was much more contained in nature, but still pointed to financial fragilities and interconnectedness in the global economy.

These events are obviously raising concerns about whether we are prepared. One of the legacies of the global financial crisis has been a greater focus on financial stability. This responsibility includes activities such as stronger preemptive monitoring of risk exposure of financial institutions, but also includes macroeconomics—improving our understanding of linkages between the United States and the rest of the world.

These are topics that we investigate here in Minneapolis, where we have a great team of international macroeconomists. And this is one of the reasons why the Fed’s model of investing in researchers is a successful one. When something like a debt crisis or a financial crisis happens with one of our trading partners, it’s good to have in-house researchers who have investigated these phenomena: What are the key transmission channels? What have we observed in the past? What policy did we use in the past and how did that play out?

It’s a hot topic lately, whether U.S. monetary policymakers should be factoring in the global impact of our actions, especially when combined with the actions of central banks around the world. Everybody is acting in response to their own domestic mandates, but influencing global economic flows. How do you think about that?

First of all, there is a network of central banks out there, not just the Federal Reserve. Central bankers get together regularly. There is no explicit coordination that takes place, but definitely an exchange of information to get a better sense of what is happening in the rest of the world.

An exercise we do regularly is to ask ourselves: How is the global economy performing and how do we see it going forward? As I said, what are the implications for the United States of a European recession? As many observers note, growth in China has diminished greatly and they are still dealing with the virus. This will, for example, imply lower exports for the United States, so in our forecasting and assessment, we factor in these developments as part of our routine policy discussions.

It’s not easy, obviously. It reveals how complicated the economic assessment has become. But it’s the standard approach nowadays to consider developments in foreign GDP, inflation, and financial markets. Take the dollar, for instance, which has appreciated quite a bit last year. It’s now at a multiyear high that implies lower import prices, but that also has implications for some of the countries that borrow in dollars as it increases their funding costs.

Like many economists, you maintain a personal website to organize your research and link to your C.V. (curriculum vitae). Unlike most of them, I see you have a section devoted to wine. And in addition to your many academic credentials, you have a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust. Tell us a little bit about what appears to be a very serious hobby.

I’m glad you asked because that’s one of my passions outside the workday. I’m originally from Italy, so I grew up with wine at the table for lunch or for meals in general. Grandpa used to have a vineyard and make wine. Harvest was a big family event. I think part of it is a way to remain connected to my birthplace.

But it happened a little bit by accident. My wife and I always enjoyed a glass of wine, and then at some point after our two kids were born, we looked for an opportunity to create time just for the two of us. So, we started going to wine tastings at a local school in D.C. We took the first class because we just wanted to get a little bit more knowledgeable about wine. But one thing led to another and eventually that passion developed into a commitment with a diploma, which is three years of coursework. We felt at times like we were basically back in college, where we had to literally take time off from work to study for the exams.

I can tell you that the day before the exam, we regretted it a bit and asked ourselves, Why are we going for the diploma? But, looking back, it was a great experience to go through. It gave me more knowledge and a framework to think about wine. And I have actually been an instructor now for a couple of years, so I’m trying to share the passion.

Jeff Horwich is the senior economics writer for the Minneapolis Fed. He has been an economic journalist with public radio, commissioned examiner for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and director of policy and communications for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He received his master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Minnesota.