Despite high mortgage rates and house prices, homeownership in the United States is rising. Two-thirds of U.S. households own their home, with an additional 7.6 million net new homeowners since 2015.

Surprisingly, the lowest-income households—that is, those that are in the bottom income quintile, or earning less than $30,961 in 2023 for a married couple—have driven this recent homeownership growth.

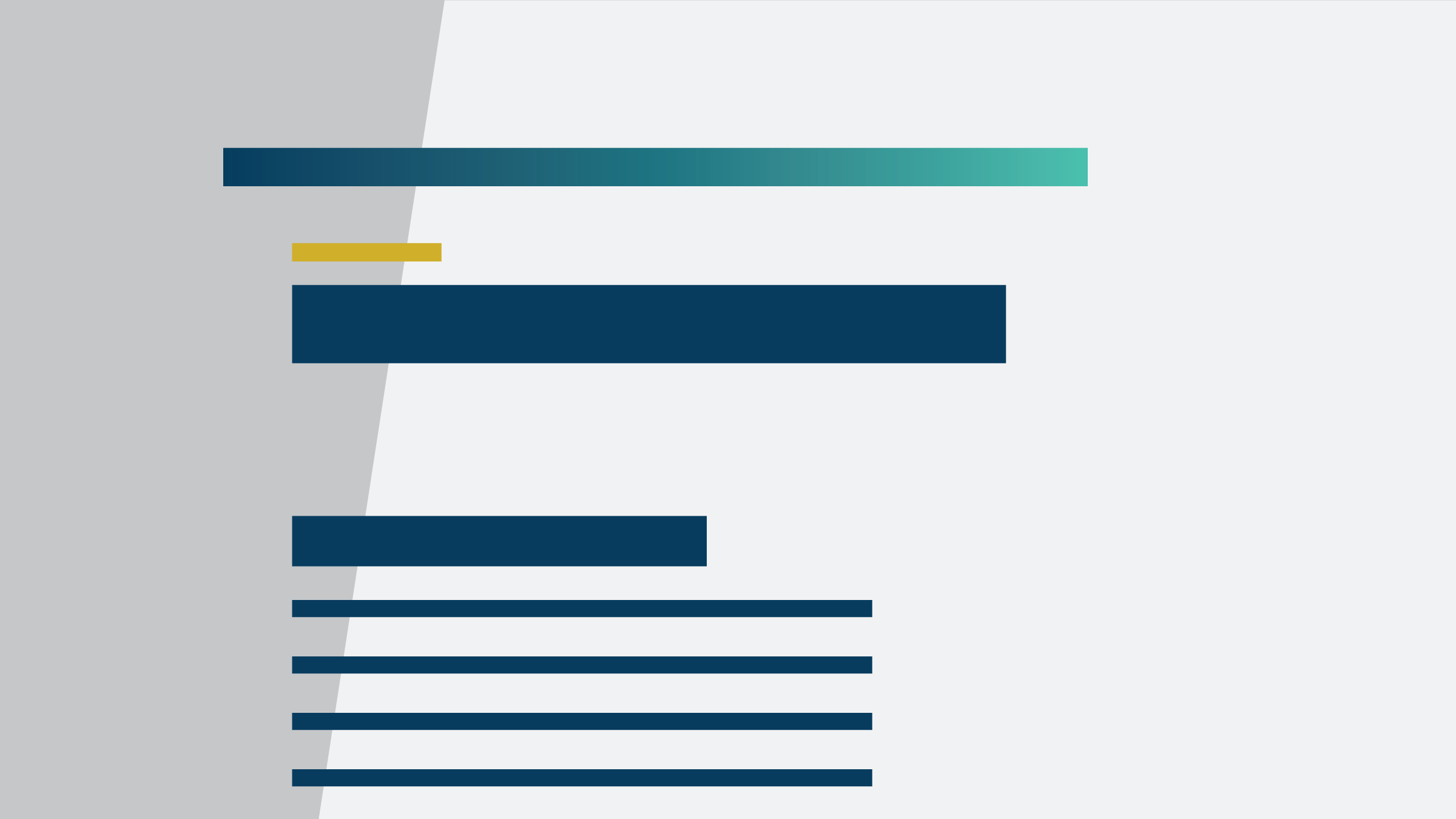

In 2023, 47.1 percent of households in the bottom fifth of the income distribution owned their homes—nearly regaining the 2005 all-time high of 47.7 percent, as shown in Figure 1.1 From 2015 through 2023, these low-income households increased their homeownership by almost 6 percentage points, mirroring a similar homeownership expansion from 1995 through 2005.

Homeownership—and the policies that affect it—is often associated with middle- and high-income households. However, our data suggest that policies affecting homeownership and housing supply would benefit from an understanding of ways to further boost homeownership for low-income families. In exploring homeownership trends among those at the low end of the income spectrum, our analysis advances the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis’ mission to pursue an economy that works for all of us.

Regardless of household income, homeownership can offer benefits

Homeownership is a central component of wealth for low-income households. Home equity is the largest asset among these households, amounting to 38 percent of their total assets. Homeownership can provide access to educational opportunities and social networks. Owning instead of renting provides long-term housing security and protection from rental inflation.

Homeownership also offers numerous benefits to families and their communities regardless of income level. Research has found that becoming a homeowner makes households more engaged in their communities through voting and involvement in community organizations. Homeowners are likelier to maintain their exterior property, increasing local home values. Homeowners are also less likely to move in response to local labor market shocks, helping to create stronger and more lasting social networks.

Still, lower-income households are less likely to own their homes than higher-income households. While 47 percent of bottom-income-quintile households were homeowners in 2023, 81 percent of the top income quintile were homeowners.2

Recent homeownership trends vary across these income groups, as shown in Figure 2. Homeownership by low-income households jumped by 5.8 percentage points from 2015 to 2023 and is up a total of 6.3 percentage points since 1995. Meanwhile, homeownership among the quintile of highest-income households nudged up just 0.7 percentage points since 2015 and remained 2.1 percentage points below 1995 homeownership levels. Homeownership growth among middle-income households (those in the 41 to 60 percent income quintile) has been similarly muted, remaining below 1995 levels and far below the early-2000s peak.

Homeowners value, among other things, having family stability, being free of the landlord-tenant relationship, seeing home prices and mortgage costs beat high rent payments, and receiving the related tax benefits. Of course, the importance of these features varies by household income or other characteristics. Younger households are more likely to be low-income and are also more mobile, which reduces homeownership’s attractiveness for them. High-income households receive greater homeownership tax benefits, which makes them more likely to choose homeownership.

Aging is contributing to homeownership gains

Age is tightly linked to homeownership. For instance, only about a quarter of all 25-year-old heads of household own their home, compared to about three-quarters of 65-year-old heads of household, with steady homeownership growth between those ages. Homeownership rates increase significantly after people achieve milestones such as getting married, having children, and securing jobs. Older households also have had more time to save for downpayments and establish a credit history to lower mortgage costs.

As it turns out, the average age of heads of low-income households was about three years older in 2023 than in 2015. That has contributed to the rise in homeownership among this group. Figure 3 breaks out low-income-homeownership trends by age group. This figure shows us that low-income homeownership has been up or roughly steady for all age groups since 2015.

Racial composition may also play a role in this trend of increased homeownership by low-income households. White and Asian low-income households are more likely to be homeowners than Black and Latino households, perhaps due to differential mortgage access and costs or intergenerational wealth transfers. Figure 4 shows low-income-homeownership trends by race and ethnicity.

In 2023, White and Asian low-income homeownership reached new highs at 58.4 and 40.0 percent, respectively, while low-income Latino homeownership peaked in 2020 at 34.4 percent. Homeownership growth since 2015 was strong for all racial groups, increasing by 6.3, 4.0, 4.5, and 12.2 percentage points for low-income White, Black, Latino, and Asian households, respectively. (Due to the limited sample size in our data source, homeownership rates among low-income Native American households are unavailable.3)

Dissecting the homeownership boom

We worked with a set of observable factors and quantified how each may explain the rise in low-income homeownership. To explore this, we performed a statistical procedure that first measures the relationship between household characteristics—such as age, income, race, and marital status—and the homeownership rate. Then, we compared actual changes in homeownership rates to our prediction of how homeownership should change given the changes in the observed characteristics.4 This analysis is similar to studies that examined the late-1990s-to-early-2000s homeownership boom and found that household characteristics such as age, marital status, and race explained little of it. These studies found that instead, the boom was driven more by mortgage credit expansion and home price expectations.

In short, our analysis compares how changes in group characteristics are associated with changes in the homeownership rate. For example, if homeownership rises by 1 percentage point for every year older a person becomes, and the average age of low-income households increases by three years, then we would attribute 3 of the 6 percentage points of homeownership increase to increasing age.

We find that 58 percent of the observed rise in low-income homeownership can be explained by changes in observable household characteristics from 2015 through 2023. Among observable characteristics, age is the most important, accounting for 36 percent of the homeownership increase. All other variables, which include marital status, race, sex, parenthood, income, citizenship status, disability status, and state, account for the other 22 percent of explained homeownership rise.

One important caveat is that household formation could play an important role in understanding this homeownership trend. Following the U.S. Census Bureau, we define income and homeownership at the household level. However, young adults have increasingly delayed forming independent households, in part due to rising home prices but also because of delayed marriage and fertility. As a result, young adults are increasingly living with their homeowning parents (a trend resulting in the term “boomerang children”) and are thus counted as homeowners, instead of living on their own and likely renting. This wrinkle in defining homeowners can influence the interpretation of homeownership trends. However, when we assign homeownership at the person level instead of the household level, this analysis continues to find a similar rise in homeownership rates, and attributes about half of that increase to household characteristics.

Putting it all together

This analysis has found that about a third of the recent rise in low-income homeownership is due to increasing age, while another quarter of the rise can be attributed to other observable factors, such as income, marital status, and race. This is in contrast to the prior homeownership expansion of the 1990s-2000s, which was not driven by observable factors. However, our analysis still leaves about two-fifths of the recent homeownership increase unexplained.

Some additional factors that could account for this homeownership trend include tax policy and housing market conditions. The Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 may be contributing to increased homeownership for low-income households, as suggested by published research. The historically low mortgage rates beginning in 2016 may also have been effective at attracting more low-income first-time home buyers or securing long-term homeownership affordability for existing low-income owners. Recent statistics support this notion by showing that foreclosure rates remain historically low.

While recent housing affordability measures frequently paint a gloomy picture for low-income households (and rightfully so), increased homeownership rates provide positive benefits, such as greater household stability, wealth building, and community participation.

Policymakers, researchers, and advocates may wish to focus on policies that could further support these recent gains in low-income homeownership. Among them:

- Lowering home prices by increasing the housing supply;

- Providing support to new or existing homeowners through programs such as downpayment assistance and subsidized mortgage rates; or

- Providing temporary support, such as unemployment insurance, following income shocks.

Those ideas and others could increase homeownership for low-income families, strengthening this cornerstone of the American Dream.

The author thanks Julie Gugin and Cristen Incitti for reviewing and commenting on a draft of this article.

Endnotes

1 Note that Figure 1 displays the three-year trailing homeownership average for the bottom income quintile (based on income per adult). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey (CPS) has tracked homeownership since 1977 and the previous high for this group was 47.6 percent in 2005. Using different definitions of low-income households—either the official poverty line, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development definition, or the bottom 10 or 20 percent of the income distribution—homeownership rates for lower-income households have still either approached or surpassed their early 2000s peaks.

2 Using data from the CPS, we assign income percentiles based on household income per adult.

3 The Center for Indian Country Development at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis is working to address economic data gaps and provide data tools and resources that center Native American people, communities, and experiences.

4 The procedure—a Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition—is a regression-based technique commonly used by economists to understand how observed factors shape differences in outcomes across groups and over time.