Over 20 percent of workers in the United States have an occupational license, typically state-issued, that is legally required for them to work in their profession. Especially when state licensing requirements vary, it can be challenging for workers to practice in their profession after moving to a new state. Each state requires individuals to apply for a new professional license and complete the associated paperwork, fees, and—potentially—additional training and exams. Low- and moderate-income workers bear a particular burden to the extent that the costs of licensing fees and delayed employment are large relative to their incomes. In turn, this burden deters interstate migration by licensed workers and can impair the efficient functioning of U.S. labor markets.

To address some of these issues, roughly 20 states have enacted universal licensure recognition (ULR) reforms with the intent of making it easier for licensed professionals to move among states and continue to work. Researchers have begun to analyze impacts of these reforms, but there has been little direct study of ULR reforms’ on-the-ground implementation. To shed light on this emerging policy, we explore the experience of Montana, which recently enacted a ULR reform. Using data from the Montana Department of Labor & Industry (DLI) and interviews with staff from that agency, we examine trends in the volume of licensing in Montana pre- and post-ULR adoption and describe the challenges licensing boards face as they adjust their practices to comply with the new policy.1

Licensure reforms like ULR are key labor market policies that can affect workers’ livelihoods. The Community Development and Engagement team at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis undertook this research as part of its mission to provide better evidence to leaders as they seek to remove labor market barriers for lower-income workers.

ULR in Montana

In recent decades, some licensing authorities have attempted to reduce interstate licensure barriers by constructing profession-specific compacts, the most well-known example being the Nurse Licensure Compact. Among other anticipated benefits, these compacts aim to make it easier for licensed individuals to work across state lines—temporarily or after a permanent move. However, a profession-specific compact can take many years to coordinate across participating states, has limited scope (i.e., it applies only to a single profession), and may result in states agreeing to higher levels of requirements than some policymakers would prefer.

ULR is designed to avoid those downsides by allowing states to set their own standards for how to acknowledge licenses from other states. In March 2019, the State of Montana enacted a ULR reform by changing one word at the beginning of the relevant state law, from “A board may issue a license to practice …” to “A board shall [emphasis added] issue a license to practice ... .” The reformed law requires boards to license out-of-state applicants if their original state license requires “substantially equivalent” education and experience. Many ULR reforms include the “substantially equivalent” standard, but some states have implemented even stronger reforms that omit that language.

Some proponents of Montana’s reform testified in legislative committees that the bill was a critical fix for workforce issues. They gave examples of workers licensed in other states who had to pay thousands of dollars for additional educational credits or who passed up opportunities because of differences in licensing requirements across states. Other supporters emphasized that the bill “simply reflects what is currently happening” or would reduce licensing-processing times.2

Montana is issuing more occupational licenses

To explore the Montana experience, we analyzed Montana DLI data on all licenses newly granted by the department from 2013 through 2022, with all data anonymized to remove personally identifiable information. For each new license, we observed the name of the license granted (e.g., master electrician license or cosmetologist license), the year it was granted, and whether it was granted via an endorsement—that is, the recognition of an out-of-state license3—as opposed to the standard pathway for those without licenses. The March 2019 reform was intended to ease the path for those seeking endorsement.

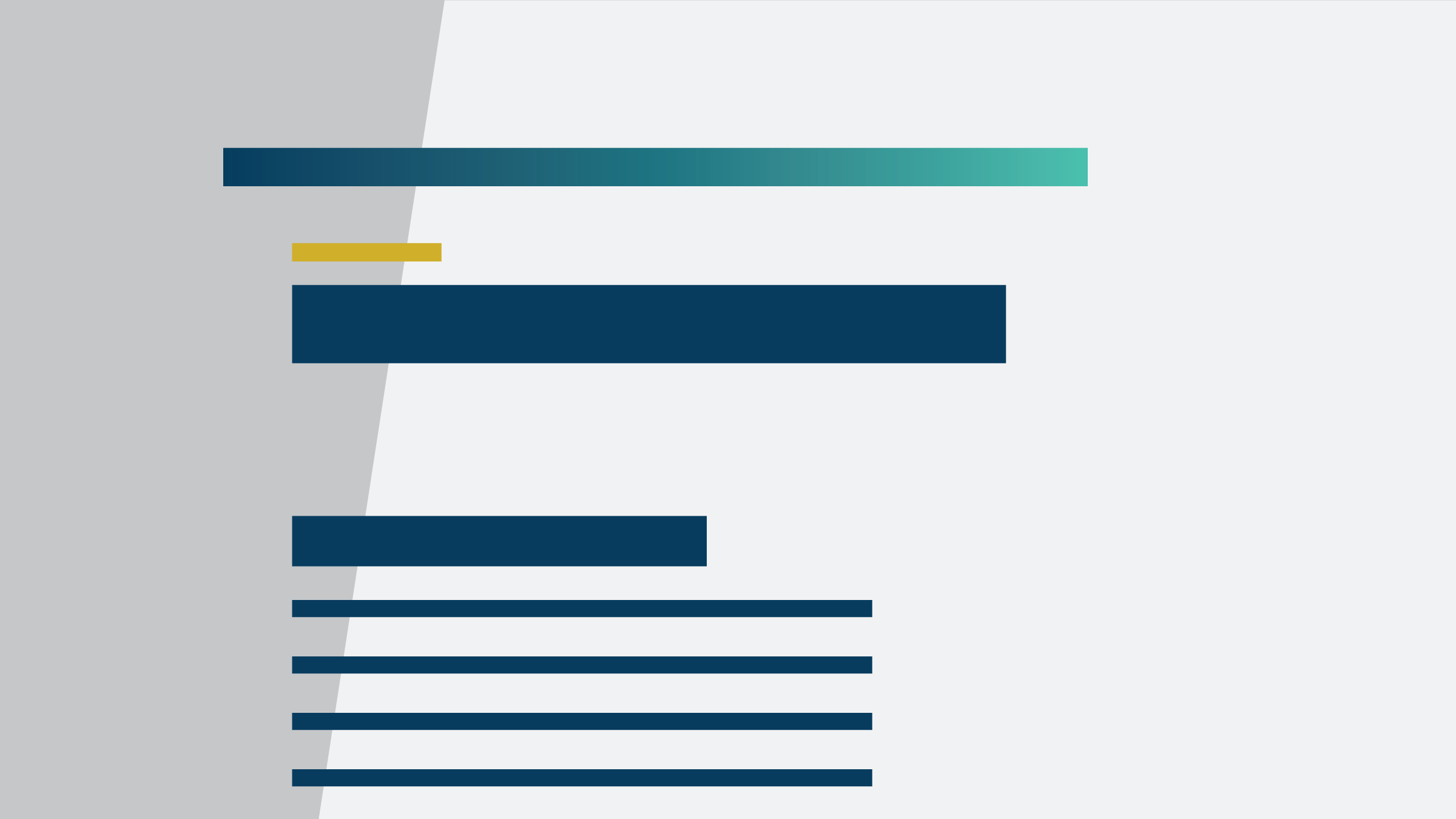

Overall, as seen in Figure 1, we observe an increase in licensing from 2012, when a total of 7,429 licenses were issued, through 2022, when a total of 15,575 licenses were issued, with particularly strong growth from 2020 through 2021. Licensure by endorsement grew especially quickly, from 2,428 licenses issued in 2012 to 7,527 in 2022.

The timing of Montana’s policy change presents some challenges in examining the data. Because the law change occurred partway through 2019, any immediate effect would be muted in that first year. And starting early in the following year, the COVID-19 pandemic had dramatic effects that may have mattered for licensing patterns. Unfortunately, the lack of data for other states makes it difficult to rigorously adjust for pandemic impacts.

For each bar in Figure 1, we note the share of licenses granted by endorsement to more clearly observe how endorsement behavior changed after the 2019 reform went into effect. Endorsement has constituted an important licensure pathway in Montana for more than a decade. As noted above, the aim of the 2019 reform was to ease the path to endorsement—specifically, by extending that option to more occupations and catalyzing changes in existing endorsement processes. As seen in Figure 1, over time a larger share of applicants have received their licenses through endorsement, with especially rapid increases in the early 2010s, when the share increased from 33 percent of all licenses in 2012 to 42 percent in 2014, and from 2019 to 2021, when the share increased from 42 percent to 48 percent. The latter increase is consistent with, but not clear evidence of, an effect of the 2019 ULR reform.

The sheer volume and growing importance of licensure by endorsement indicate that ULR and similar reforms have the potential to substantially impact both licensed workers and the overall labor market. However, the existing data alone do not permit us to confidently state how the 2019 policy change affected licensure of out-of-state-licensed applicants, either in the short or the long run. Moreover, ULR reform may have effects on outcomes not well described by the data, like time to licensure and the overall burden for administrators and applicants.

Challenges for implementation

Because the data leave many questions unanswered, and because the decentralized nature of licensing processes in Montana means that no single entity can answer them all, we spoke with several executive officers of Montana licensing boards to gain more insight into how ULR reform has and hasn’t affected licensing in the state. We uncovered some key similarities and differences in how boards approached the change.

In response to the 2019 reform, all leaders we interviewed had initiated a thorough review of requirements in other states to identify which states have requirements that are substantially equivalent to Montana’s. They all aspired to move to a system where applicants who were applying for a license by endorsement from a substantially equivalent state would only have to provide a verified current license, pass a background check, and complete a disciplinary review. Interviewees stressed that it took a lot of research and time to properly identify which states had substantially equivalent requirements. We took the interviewees’ comments as an indication that the “substantially equivalent” ULR provision is an important one, with implications for how licensing boards operate and, potentially, for the effectiveness of ULR. “Substantially equivalent” clauses can help ensure that out-of-state licensing applicants have met similar requirements as in-state applicants, but that must be weighed against the diminished reach of ULR policies to applicants from states deemed not to have substantially equivalent standards.

The executive officers also emphasized that it took considerable effort to change ingrained practices. Boards that already endorsed out-of-state licenses found it challenging to shift from examining the experience and credentials of a given applicant to a simpler, faster process of first checking whether an applicant’s license was issued by a state that meets the substantial-equivalency standard. Many boards have yet to implement this transformation in how they process out-of-state license applications. As a result, prospective applicants may face a dearth of clear, accessible guidance about what information they need to submit with their applications, which in turn can waste their time and deter them from applying.

Boards that did not endorse substantially equivalent licenses prior to the 2019 reform faced even bigger barriers to changing their practices. The electrical board, for example, had to begin a process to change rules that directly conflicted with the 2019 policy and prohibited licensure by endorsement for master electricians. That board was working on changing its rules this year to allow for substantial-equivalency endorsement. Figure 2 shows that although a steady number of journeyman electrician licenses were issued via endorsement over the past decade, no master electrician licenses had been issued via endorsement through the end of 2022 (when our sample period ends).

No master electrician licenses have been issued via endorsement

Source: Authors’ calculations using administrative data from the Montana Department of Labor & Industry

The full impact of the 2019 reform has taken considerable time to materialize, with each board working through its own individualized process for compliance.4 Licensing boards that already endorsed out-of-state licenses could make changes more quickly, but these changes are still in progress and seem most likely to affect processing time, as opposed to dramatically increasing the number of licenses issued. Unfortunately, this is not an outcome we can observe in our data. Conversely, for boards that previously barred licenses by endorsement, as in the master electrician case, the potential policy impact is much larger, albeit delayed. Once rules are changed to align with the obligation to grant licenses by endorsement for out-of-state applicants, there may be a more readily observable impact of the 2019 reform.

While it is not possible for us to make a definitive statement about ULR effects, the data—along with our interviews with licensing authorities—help illuminate the workings of ULR and the challenges in its implementation. Further research on the “substantially equivalent” provision and the potential benefits of centralized administration would advance understanding of the effects of ULR reforms.

The authors thank Kihwan Bae, Zaakary Barnes, and Carolyn Dennis for insightful comments and feedback on an earlier draft. The authors are also grateful to the Montana DLI for sharing the data featured in the article, and to interviewees who provided crucial context.

Endnotes

1 Minneapolis Fed staff spoke with four executive officers and one staff member of Montana licensing boards in January and February 2024.

2 These statements were made in hearings in the Montana State Legislature on February 1, 2019, and February 19, 2019.

3 In our data, licenses can be granted via endorsement when a multi-state compact determines a standard set of requirements for an occupation, or when a licensing board determines that a specific state has sufficiently similar requirements to those of its own state.

4 To accelerate this, some states (e.g., Pennsylvania) have taken actions like specifying a response timeline that boards must meet when processing licensure applications, or centrally monitoring the number of accepted and rejected applications.

More On

Ayushi Narayan conducts research on labor market institutions to help the Community Development and Engagement team understand how employment-related policies and trends affect low- and moderate-income communities. Prior to joining the Bank, her work included roles at the Council of Economic Advisers, Nike, and Amazon.