Child care costs can be jaw-droppingly high. For example, the median tuition for infants in a licensed child care center in the Twin Cities metro tops $17,000 a year.* Still, some researchers argue that the market price of child care is generally too low to support all the inputs necessary to provide an abundant, accessible supply of high-quality care.

According to Aaron Sojourner, a professor at the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota, “We need to differentiate between the cost and the price of child care.” In Sojourner’s view, focusing solely on the current market price for high-quality care neglects important issues that affect how much it costs providers to create a high-quality care environment that promotes children’s healthy development.

Sojourner believes that because the market price is not high enough to support an adequate supply of high-quality care, the nation is underinvesting in our children’s first years. He described these years as “a scarce and precious resource.”

Not all families face the same price …

Understanding the child care market is critical for policymakers with an interest in supporting early childhood development. Data on child care providers reveal significant variation in child care prices and availability depending on a family’s location, the ages of its children, and the hours of the day those children need a caregiver. Demand for providers that speak the family’s language and offer culturally reflective care practices can also have important implications for price and supply.

Chris Herbst’s analysis of child care price trends underlines the complex nature of the market. His work estimates an overall 14 percent increase in the price of child care from 1990 to 2011, though prices largely stabilized in the new century. The price change over that period looked very different for families depending on their characteristics, however.

Herbst, an associate professor in Arizona State University’s School of Public Affairs, found that the price increase was actually 30 percent for families with children under age five. He also found that the long-term price increase was largely driven by families with higher earnings. In other words, families with more financial resources were more likely to spend more on child care.

… and not all parents find high quality

Just because prices have been stable doesn’t mean they are affordable, Herbst cautions. The data don’t capture many of the families that opt out of licensed child care because of the price. And they don’t reveal how much families with lower incomes would invest in their child’s care if they had the ability to pay.

“The data I’ve looked at paint a less dire picture about the trends in market prices for child care,” he said. “But if we’re producing the socially optimal amount of high-quality child care, those prices will surely go up—which is why it’s important to invest in child care subsidies [for low-income families].”

Market forces alone may not drive an overall increase in child care quality, he said, because many parents lack access to reliable information. Studies incorporating everything from Yelp reviews to classroom observations show that parents are often unable to discern the quality level of a care provider.

“For parents, child care is a classic ‘experience good,’” said Herbst. “You only know how good it is once your kids have consumed it for a while.”

Sojourner’s analysis of data from the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP), an early intervention program for low birthweight and premature babies, shows that access to the high-quality IHDP yielded higher, more persistent developmental gains for families with low incomes. Children from families with higher incomes that had access to the same program saw short-term gains that largely faded out as they aged, relative to their peers from families with similar incomes who were able to afford care of similar quality without the subsidy.

Many states assist parents in identifying high-quality child care providers by constructing quality rating improvement systems (QRISs). States define quality as part of their QRIS implementation process, then rate providers using a scale. Generally, participation in QRISs is voluntary for child care providers.

Herbst’s research suggests that introduction of QRISs in states leads to slightly higher workforce participation for mothers and higher demand for child care. Notably, QRIS introduction leads to greater usage of licensed child care providers for families with higher income, while families with lower incomes tended to shift to informal care, as provided by family, friends, and neighbors.

The shift could occur for multiple reasons, he said. For example, parents with fewer resources may assume that higher-rated programs are beyond their reach. The results of his analysis lead him to encourage policymakers to put more resources into building awareness about QRISs.

QRISs also have an impact on the child care workforce.

“My findings suggest that QRISs can be a double-edged sword,” Herbst said. Since QRISs result in both increased job turnover rates and a more highly trained workforce, policymakers may be concerned about QRISs’ impact on child care professionals with less formal training. Given the relatively low pay in the field, child care workers may lack both the opportunities and the resources to pursue training. Herbst suggests that the wage supplements tied to some QRISs can mitigate some of the negative impacts of QRIS implementation on child care workers.

Consumers in the child care marketplace

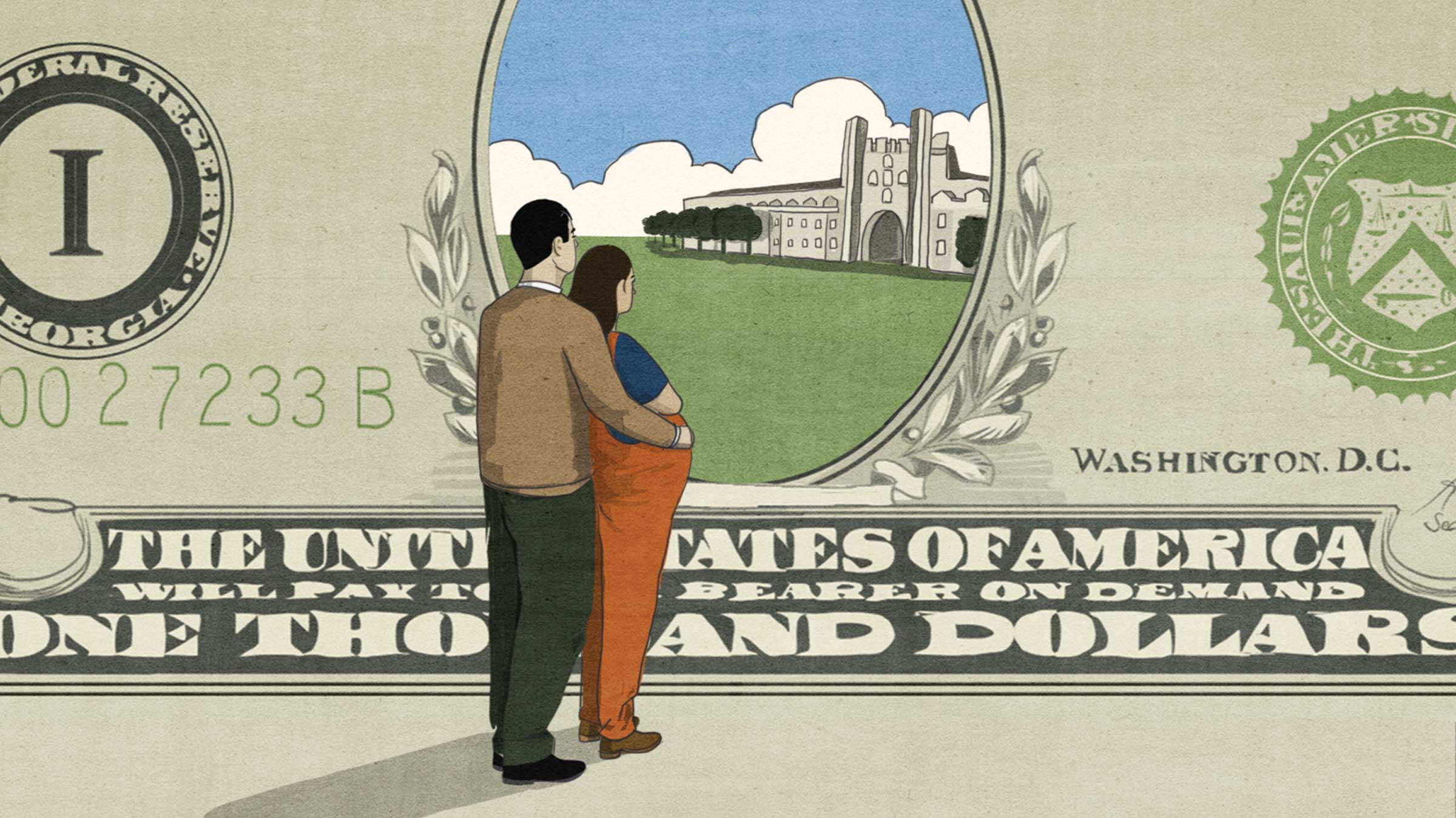

Child care is the least affordable—and may have the biggest impact—for families with few private resources. Meanwhile, public resources invested in young children are far outpaced by those invested in school-age children.

“We ask the most of families when they have the least,” Sojourner said.

—Aaron Sojourner, University of Minnesota

Sojourner has analyzed the average hourly wage and hours worked of parents with at least one child under age 18. He compares the two measures across parents based on the age of their youngest child. Parents with older children earn more per hour and are likely to work longer hours than their counterparts with younger children. The starkest differences occur between those with children under age 3 and those with children over age 14.

These findings make intuitive sense. Younger children are likely to have younger parents. Younger parents are likely to have less experience in the workforce and thus have lower earning power.

Given the combination of infants’ parents’ lower incomes and providers’ higher prices for infant care, it is unsurprising that America’s youngest children are much more likely to spend time in the care of a parent or in an informal care environment. On average, infants spend only about five hours a week in a formal care environment, such as a child care center. School-aged kids spend about half their time in a school setting, even after accounting for summer vacations.

Such data, when combined with Sojourner’s IHDP analysis and other evidence on the returns to public investment in high-quality early childhood development programs, lead Sojourner to urge greater investments in early childhood development programs.

“Investment influences child development,” Sojourner said. “Lack of investment also has an impact. The [income-based] skills gap we see [in older children] is driven by parents’ choices, but also by our policy choices. We have to own that.”

Herbst agrees, and also argues that child care subsidies should not be tied to workforce participation by parents and should instead focus on giving better access to high-quality care for all low-income children. After all, he pointed out, children’s development should be nurtured, regardless of whether their parents are employed.

“The original child care subsidy system should be divorced entirely from the welfare system and subsidize child care regardless of a parent’s work status,” he said.

Chris Herbst and Aaron Sojourner presented on day one of the Minneapolis Fed’s Innovation in Early Childhood Development and K-12 Education Conference, which took place on October 23–24, 2018. A video and slides from their session, “Policies to Improve Quality in Early Care and Education Markets,” are available on the conference web page.

Endnotes

* Based on rates listed in Results of the Child Care Market Survey: Minnesota Child Care Provider Business Update, published by the Minnesota Department of Human Services in March 2017.

Return to “Exploring innovation in early childhood development” article index